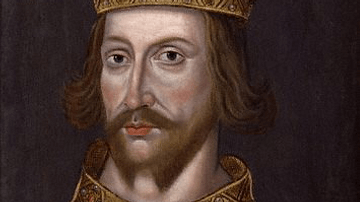

William I of Scotland, also known as 'William the Lion' after his heraldic emblem, reigned from 1165 to 1214 CE. Succeeding his elder brother Malcolm IV of Scotland (r. 1153-1165 CE), William was faced with a shrinking kingdom, but he harboured ambitions to capture northern England, especially Northumberland. While campaigning south of the border in 1174 CE, William was ignominiously captured by English knights and imprisoned until he negotiated with Henry II of England (r. 1154-1189 CE) for his release. William was obliged to become Henry's vassal, give up key castles in Scotland and defer to the English Church. Scotland bought back its freedom from Richard I of England (r. 1189-1199 CE) but then lost it again to King John of England (r. 1199-1216 CE). Despite the ups and downs concerning his relations with English kings, William ruled Scotland for longer than any other medieval Scottish monarch and did much to consolidate his kingdom and extend the Crown's rule over the entire northern British Isles. When he died in 1214 CE he had ruled for 49 years; he was succeeded by his son Alexander II of Scotland (r. 1214-1249 CE)

Early Life

William was born c. 1142 CE, a member of the ruling House of Canmore. His mother was Ada de Warenne, daughter of the Earl of Surrey, and his father was Henry, Earl of Northumberland (d. 1152 CE), the son of David I of Scotland (r. 1124-1153 CE) who had died before he could inherit the throne. The crown had passed to David's nominated successor, his grandson Malcolm IV of Scotland, but he died of natural causes in his mid-twenties and without children. Malcolm's reign had seen Scotland lose much of the gains in English territory that his grandfather David I had acquired through battles and diplomacy. England had proved resurgent under the guidance of Henry II of England. William became king on 9 December 1165 CE and was invested at Scone on Christmas Eve.

The king's sister was the duchess of Brittany, and visits to her permitted William to participate in medieval tournaments like other European kings and nobles. William cut a dashing figure with his red hair and fighting prowess. The king's nickname 'the Lion' was a posthumous one and is most likely because William had chosen that animal as his heraldic badge. The design of this badge was a red lion rampant on a yellow background, and it became the emblem of Scottish monarchs thereafter; today it is known as the Royal Banner of Scotland. William fathered a host of illegitimate children but finally married on 5 September 1186 CE to Ermengarde de Beaumont (d. 1234 CE), herself an illegitimate descendant of Henry I of England (r. 1100-1135 CE). The couple would have four children: Alexander, Margaret, Isabel, and Marjorie.

Government

David I had gone a long way to forging a unified Scottish kingdom but there were still some pockets of resistance to overlordship by the Crown after Malcolm IV's lacklustre reign. These were notably in the southwest and far north, which William crushed. Galloway, in the southwest corner of the kingdom, tried to split from Scotland, but that idea was quashed when William captured Gilbert, lord of Galloway in 1176 CE. However, Galloway never truly settled back into the kingdom until 1186 CE. There was one more area of trouble, the Ross region in the far north. Rebellions were stirred up by the earl of Orkney in 1181, 1197, and 1202 CE. The troublesome earl was dealt with after William grabbed his son as a hostage and then blinded and castrated him. Another troublemaker, also in Ross, was Donald mac William, the illegitimate grandson of Duncan II of Scotland (r. 1094 CE). Donald was killed in battle in 1187 CE and his head presented to William at Inverness. Many of these troubles, which simmered on throughout his reign, had their root cause in William's capture and then submission to Henry II of England (see below). The Scottish king's ongoing struggle to dominate the whole of what is today Scotland led to his other nickname of Uilleam Garhh or 'William the harsh'.

King William expanded the system of sheriffdoms that David I had established and continued with the policy of creating royal burghs with protection and privileges which promoted trade, notably at Invernairn (c. 1187 CE), Dumfries (c. 1185 CE), and Perth (c. 1209 CE). The areas of Angus and Mearns were brought under tighter royal control, too. Justices and sheriffs were given wider powers, and the criminal laws made clearer across Scotland. Like his grandfather, William was keen on establishing monasteries; he founded Arbroath Abbey in 1178 CE, which became one of the richest in Scotland thanks to the king's generosity.

Relations with England: Henry II

The English king Henry II had negotiated the return of Cumbria and Northumbria from Malcolm IV, conferring on him in return the earldom of Huntingdon (which had been his father's) and allowing the Scottish king to keep the castle at Wark-upon-Tyne in 1157 CE. William was determined to get Northumberland back again. This region had been his father's earldom and briefly his until Malcolm had given it away. In 1168 CE William signed an alliance with France, the arch-enemy of Henry II. William then invaded Northumberland in July 1174 CE, one pretext being the infamous murder of Thomas Beckett, the archbishop of Canterbury in 1170 CE, chopped down in his own cathedral by knights supporting Henry II.

William, taking advantage of the English king being distracted by his own troubles dealing with a rebellion in England and Normandy, captured the royal castles at Brough and Appleby. However, William was caught by surprise on 13 July 1174 CE near Alnwick Castle by a small group of English knights. The king's horse was killed and fell on him so that William could not escape capture. The Scottish king was then imprisoned in faraway Normandy for five months and allowed to ponder on his future.

The capture of his rival meant that Henry II was able to bargain with William for his freedom. The consequence was a treaty which formally recognised Henry's overlordship of Scotland, the Falaise agreement of December 1174 CE. On 10 August 1175 CE, William had to perform a public exhibition of surrender at York and give Henry control of five important castles: Edinburgh, Berwick, Roxburgh, Jedburgh, and Stirling. For a little extra salt in the wound, Henry insisted that William pay for the English garrisons within these castles. A final concession was to permit the English Church supremacy over the Church of Scotland, a situation not remedied until the Pope's intervention in 1192 CE. Things did improve a little in 1186 CE when Henry arranged for his cousin Ermengard to marry William and the English king gave Edinburgh Castle back to the Scots as a wedding present.

Richard I & King John

With other similar treaties of overlordship for Wales (1163 CE) and Ireland (1175 CE), Henry II was now in control of the whole British Isles. As usual in the medieval period, though, when one king died, his successor often proved less than able to keep the gains of his predecessor. And so it was with Henry II who was succeeded by his sons Richard I of England and then King John of England. Richard was mostly busy in the Middle East on the Third Crusade (1189-1192 CE), and John proved one of England's most unpopular ever kings.

Richard I, aka ' Richard the Lionheart', was always looking for cash to fund his crusade and so William was able to buy himself out of the overlordship Henry II had subjected him to. This 1189 CE agreement is known as the quitclaim of Canterbury. Signed on 5 December, the agreement gave William back several castles that Henry had taken over and formally declared Scotland's independence. The price was 10,000 marks. A few years later, as Richard continued to look for funds to bankroll his army, it seemed the English king was willing to concede Northumberland to William at the right price. The Scottish king was finally going to get what he had longed for all his life but, alas, Richard decided to think about the deal and left England again, this time to defend his family's lands in France. Richard was killed during a siege in 1199 CE, and William's deal was never realised.

The whole Canterbury agreement with Richard I proved to be a temporary resolution as, despite his reputation as an oppressive and incompetent ruler, the next English king had different ideas. King John raised a large army and forcefully resisted the incursions of William into the north of England. He then obliged him to accept John as his feudal overlord in September 1209 CE. Under the Treaty of Norham, William was obliged to pay John 15,000 marks and provide two of his daughters (Margaret and Isabel) as hostages to ensure compliance with his return to vassal status. At least William got some value for his money when, in 1212 CE, John sent an army to Scotland to help quash a rebellion aimed at toppling the Scottish king.

Death & Successor

William died on 4 December 1214 CE at Stirling Castle, and he was buried at Arbroath in the abbey he had founded. William was succeeded by Alexander II of Scotland, who supported the northern barons in England against the unpopular King John and so contributed to the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215 CE. The charter limited English royal power and emphasised the primacy of the law over all, including the monarchy. The Magna Carta also contained a clause that reinstated Scotland's independence from England, revoking the Treaty of Norham. Alexander was even more ruthless than his father in dealing with opposition in his kingdom, and peaceful relations were restored with England after his marriage to Joan, sister of Henry III of England (r. 1216-1272 CE). The House of Canmore would continue to rule Scotland until the death of Alexander III of Scotland (r. 1249-1286 CE), grandson of William I.