Greek theatre began in the 6th century BCE in Athens with the performance of tragedy plays at religious festivals. These, in turn, inspired the genre of Greek comedy plays. The two types of Greek drama would be hugely popular and performances spread around the Mediterranean and influenced Hellenistic and Roman theatre.

As a consequence of their lasting popularity, the works of such great playwrights as Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes formed the foundation upon which all modern theatre is based. In a similar way, the architecture of the ancient Greek theatre has continued to inspire the design of theatres today.

The Origins of Tragedy

The exact origins of tragedy (tragōida) are debated amongst scholars. Some have linked the rise of the genre to an earlier art form, the lyrical performance of epic poetry. Others suggest a strong link with the rituals performed in the worship of Dionysos such as the sacrifice of goats - a song ritual called trag-ōdia - and the wearing of masks. Indeed, Dionysos became known as the god of theatre and perhaps there is another connection - the drinking rites which resulted in the worshippers losing full control of their emotions and in effect becoming another person, much as actors (hupokritai) hope to do when performing. The music and dance of Dionysiac ritual was most evident in the role of the chorus and the music provided by an aulos player, but rhythmic elements were also preserved in the use of first, trochaic tetrameter and then iambic trimeter in the delivery of the spoken words.

A Greek Tragedy Play

Plays were performed in an open-air theatre (theatron) with wonderful acoustics and seemingly open to all of the male populace (the presence of women is contested). From the mid-5th century BCE entrance was free. The plot of a tragedy was almost always inspired by episodes from Greek mythology, which we must remember were often a part of Greek religion. As a consequence of this serious subject matter, which often dealt with moral right and wrongs and tragic no-win dilemmas, violence was not permitted on the stage, and the death of a character had to be heard from offstage and not seen. Similarly, at least in the early stages of the genre, the poet could not make comments or political statements through his play.

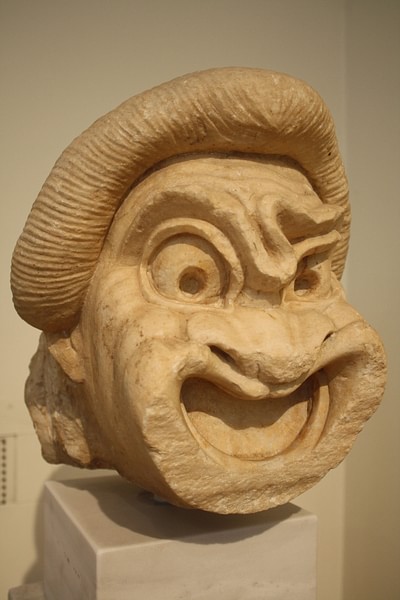

The early tragedies had only one actor who would perform in costume and wear a mask, allowing him to impersonate gods. Here we can see perhaps the link to earlier religious ritual where proceedings might have been carried out by a priest. Later, the actor would often speak to the leader of the chorus, a group of up to 15 actors (all male) who sang and danced but did not speak. This innovation is credited to Thespis c. 520 BCE (origin of the word thespian). The actor also changed costumes during the performance (using a small tent behind the stage, the skēne, which would later develop into a monumental façade) and so break the play into distinct episodes. Later, these would develop into musical interludes. Eventually, three actors were permitted on stage but no more - a limitation which allowed for equality between poets in competition. However, a play could have as many non-speaking performers as required, so that plays with greater financial backing could put on a more spectacular production. Due to the restricted number of actors then, each performer had to take on multiple roles where the use of masks, costumes, voice, and gesture became extremely important.

Competition & Celebrated Playwrights

The most famous competition for the performance of tragedy was as part of the spring festival of Dionysos Eleuthereus or the City Dionysia in Athens. The archon, a high-ranking official of the city, decided which plays would be performed in competition and which citizens would act as chorēgoi and have the honour of funding their production while the state paid the poet and lead actors. Each selected poet would submit three tragedies and one satyr play, a type of short parody performance on a theme from mythology with a chorus of satyrs, the wild followers of Dionysos. The plays were judged on the day by a panel, and the prize for the winner of such competitions, besides honour and prestige, was often a bronze tripod cauldron. From 449 BCE there were also prizes for the leading actors (prōtagōnistēs).

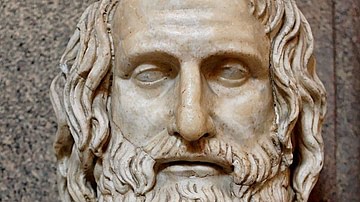

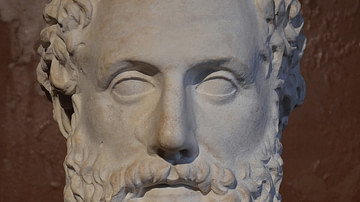

Playwrights who regularly wrote plays in competition became famous, and the three most successful were Aeschylus (c. 525 - c. 456 BCE), Sophocles (c. 496-406 BCE), and Euripides (c. 484-407 BCE). Aeschylus was known for his innovation, adding a second actor and more dialogue, and even creating sequels. He described his work as 'morsels from the feast of Homer' (Burn 206). Sophocles was extremely popular and added a third actor to the performance as wells as painted scenery. Euripides was celebrated for his clever dialogues, realism, and habit of posing awkward questions to the audience with his thought-provoking treatment of common themes. The plays of these three were re-performed and even copied into scripts for 'mass' publication and study as part of every child's education.

Greek Comedy - Origins

The precise origins of Greek comedy plays are lost in the mists of prehistory, but the activity of men dressing as and mimicking others must surely go back a long way before written records. The first indications of such activity in the Greek world come from pottery, where decoration in the 6th century BCE frequently represented actors dressed as horses, satyrs, and dancers in exaggerated costumes. Another early source of comedy is the poems of Archilochus (7th century BCE) and Hipponax (6th century BCE) which contain crude and explicit sexual humour. A third origin, and cited as such by Aristotle, lies in the phallic songs which were sung during Dionysiac festivals.

A Greek Comedy Play

Although innovations occurred, a comedy play followed a conventional structure. The first part was the parados where the Chorus of as many as 24 performers entered and performed a number of song and dance routines. Dressed to impress, their outlandish costumes could represent anything from giant bees with huge stingers to knights riding another man in imitation of a horse or even a variety of kitchen utensils. In many cases the play was actually named after the Chorus, e.g., Aristophanes' The Wasps.

The second phase of the show was the agon which was often a witty verbal contest or debate between the principal actors with fantastical plot elements and the fast changing of scenes which may have included some improvisation. The third part of the play was the parabasis, when the Chorus spoke directly to the audience and even directly spoke for the poet. The show-stopping finale of a comedy play was the exodos when the Chorus gave another rousing song and dance routine.

As in tragedy plays, all performers were male actors, singers, and dancers. One star performer and two other actors performed all of the speaking parts. On occasion, a fourth actor was permitted but only if non-instrumental to the plot. Comedy plays allowed the playwright to address more directly events of the moment than the formal genre of tragedy. The most famous comedy playwrights were Aristophanes (460 - 380 BCE) and Menander (c. 342-291 BCE) who won festival competitions just like the great tragedians. Their works frequently poked fun at politicians, philosophers, and fellow artists, some of whom were sometimes even in the audience. Menander was also credited with helping to create a different version of comedy plays known as New Comedy (so that previous plays became known as Old Comedy). He introduced a young romantic lead to plays, which became, along with several other stock types such as a cook and a cunning slave, a popular staple character. New Comedy also saw more plot twists, suspense, and treatment of common people and their daily problems.

Legacy

New plays were continuously being written and performed, and with the formation of actors' guilds in the 3rd century BCE and the mobility of professional troupes, Greek theatre continued to spread across the Mediterranean with theatres becoming a common feature of the urban landscape from Magna Graecia to Asia Minor. In the Roman world plays were translated and imitated in Latin, and the genre gave rise to a new art form from the 1st century BCE, pantomime, which drew inspiration from the presentation and subject matter of Greek tragedy. Theatre was now firmly established as a popular form of entertainment and it would endure right up to the present day. Even the original 5th-century BCE plays have continued to inspire modern theatre audiences with their timeless examination of universal themes as they are regularly re-performed around the world, sometimes, as at Epidaurus, in the original theatres of ancient Greece.