The Achaemenid Persian Empire functioned as well as it did because of the efficient bureaucracy established by its founder Cyrus the Great (r. c. 550-530 BCE) which was administered through the satrapy system. A Persian governor of a province was known as a satrap (“protector of the kingdom” or “keeper of the province”) and the province as a satrapy.

Theses satrapies were required to pay taxes and provide men for the empire's armies and, in return, were supposed to enjoy the protection and affluence of the empire as a whole. Under the reigns of some kings – like Cyrus the Great or, after initial revolts, Darius the Great (r. 522-486 BE) – the satrapy system worked well, while under others, satraps rebelled repeatedly.

Overall, however, the satrapy system functioned efficiently and would be kept by the empires which succeeded the Achaemenid – the Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE), Parthia (247 BCE - 224 CE), and the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE). Satraps are mentioned in the biblical books of Ezra, Esther, and Daniel as essential to the administration of the government and this view is supported by Persian records and ancient historians including Herodotus and Ctesias. The Achaemenid model of Persian government was so efficient that the Roman Empire would later copy it and succeeding governments in Late Antiquity would copy Rome's.

Persian governors and the satrapy system, in fact, established the paradigm recognizable in the present day of a central government, which functions through a decentralized system of subordinates responsible for governing local regions. The satrapy system is probably most clearly evident in the governmental system of the United States of America, which famously modeled itself on that of Rome just as many nation-states had centuries before.

Origins of the System

Satraps did not originate with the Achaemenid Empire, however, but with the much earlier Akkadian Empire (2334-2083 BCE) but the Akkadian officials were not known as 'satraps' which was a Persian term. Sargon of Akkad (r. 2334-2279 BCE) instituted a system of regional governors, responsible directly to him, whose activities were then monitored by more closely trusted officials. This system was copied by the Assyrians and revised by Tiglath Pileser III (r. 745-727 BCE) who instituted an intricate network of governors supervised by “trusted men” who, like the Akkadian overseers, ensured the loyalty and efficiency of the governors. This model was so effective it was later used by the Assyrians' enemies, the Medes, who were the most immediate influence on the Persian system.

The Median satrapy system is thought to have been instituted by the first king of the Medes, Dayukku (known to the Greeks as Deioces, r. 727-675 BCE), who established the Median Kingdom in Ecbatana. Deioces did unite the Medes under a kingship but, according to Herodotus (I. 102), it was his son Phraortes (r. c. 647 - c. 625 BCE) who enlarged the kingdom and founded the Median Empire, so it is more likely satrapy was established toward the beginning of his reign.

The system was firmly in place by the time of the reign of Deioces' grandson Cyaxares of Media (r. 625-585 BCE) whose daughter (or granddaughter) Amytis of Media (l. 630-565 BCE) would marry Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon (r. 605/604-562 BCE). Satraps were an integral aspect of Babylonian government under Nebuchadnezzar II's reign and their importance is referenced in the later Book of Daniel (composed c. 2nd century BCE) which casts the heroes of Daniel 3 - Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego – as either satraps or royal secretaries. These three refused the royal edict to venerate a graven image instead of their god and are condemned to die in the fiery furnace but were saved through their faith and emerged unharmed.

This basic plot is repeated in Daniel 6 where the prophet Daniel is depicted as an administrative overseer – one of the “trusted men” of a monarch – who is condemned by the Babylonian and Median satraps for worshipping a foreign god in defiance of the mandate of the king Darius. The Darius of the Book of Daniel does not correspond to any known king (although some scholars associate him with Astyages of Media, r. 585-550 BCE) and should not be confused with the Achaemenid monarchs of the same name. In the story, the satraps themselves have introduced the ordinance which allows them to condemn Daniel and, although it is not explicitly stated, they most likely have done so because Daniel is the eyes and ears of the king who would report any dishonesty or lapses by a satrap.

The importance of a trusted overseer to a king, as opposed to the value of the satraps, is emphasized in the Book of Daniel when Daniel is cast into the lion's den, emerges unharmed by the protection of his god, and Darius then has the satraps who condemned him fed to the lions. Although written much later than the events it purports to narrate (such as the reign of Nebuchadnezzar), the story illustrates the central dynamic of the relationship between a monarch and his satraps: the provincial governors could not always be trusted and would work for their own self-interest when they could which necessitated the position of the “trusted man” to supervise them. This dynamic would remain a constant of the satrapy system.

Achaemenid Satrapy

Cyrus the Great was well aware of this and so adopted and refined the Assyrian and Median system. The satraps of the Achaemenid Empire ruled for life (or unless they offended the emperor), and the position was hereditary. Further, they often governed immense areas of vast resources and the temptation to use these to unseat the emperor and create their own dynasty had to be neutralized. Scholar A. T. Olmstead describes Cyrus' solution:

To meet this threat, certain checks were instituted: [the satrap's] secretary, his chief financial official, and the general in charge of the garrison stationed in the citadel of each of the satrapal capitals were under the direct order of, and reported directly to, the great king in person. Still more effective control was exercised by the “king's eye” (or “king's ear” or “king's messenger”) who every year made a careful inspection of each province. (59)

Under Cyrus' reign, the satrapy system worked well, but under his son Cambyses II (r. 530-522 BCE), there were revolts, and when Cambyses II died and Darius I (a distant cousin) took the throne, whole regions rose in revolt. Even though Darius I, in his famous Behistun Inscription, insists that only some regions revolted, resistance to his reign was more widespread. This was because of a coup that had taken place earlier while Cambyses II had been in Egypt. His brother, Bardiya, had taken the throne and was more popular than Cambyses II. In his inscription, however, Darius I claims that Cambyses II had murdered Bardiya before going to Egypt and the “Bardiya” who claimed kingship was an imposter named Gaumata. Darius I's assassination of this imposter, therefore, was simply the return of the throne to a legitimate claimant, not a coup.

Darius I's claim was only initially supported by two satraps – Dadarshish of Bactria and Vivana of Arachosia. As Olmstead notes, “the whole empire accepted Bardiya without question [but] his assassination brought renewed hopes of national independence which bred a perfect orgy of revolts among the subject peoples” (110). Darius I spent the first few years of his reign putting down these revolts and then further revised the satrapy system to ensure complete obedience to the king's will.

Darius I kept the basic system instituted by Cyrus the Great but divided the empire into seven regions and each region into twenty satrapies which shrank the resources available to each individual satrap. The Royal Secretary, Royal Treasurer, and Garrison Commander of each satrapy were – as under Cyrus – responsible wholly to the king, not the satrap, and reported directly to the royal house. Darius I's model would keep the Achaemenid Empire intact throughout the remainder of its history, but this is not to say it was never challenged.

The Satrap Revolts

In the reign of Artaxerxes II Memnon (r. 404-358 BCE), his brother, Cyrus the Younger (satrap of Lydia, d. 401 BCE) rebelled in an attempt to unseat the king and rule the empire himself. Artaxerxes II only learned of the army marching toward him late but still was able to mount a defense thanks to the satrap Tissaphernes (l. 445-395 BCE), also satrap of Lydia. Cyrus' revolt was crushed, and he was killed in battle by Artaxerxes II who then directed his army against Cyrus' Greek mercenaries. The story of the Greek warriors' escape from Persia to the Black Sea and back to their homes is famously told by Xenophon (l. 430 - c. 354 BCE) in his Anabasis.

Artaxerxes II's reign did not continue smoothly afterwards, however, as trouble arose again in the Great Satrap's Revolt of 372-362 BCE. The revolt was initiated by some satraps' dissatisfaction with Artaxerxes II's policies but would never have launched without support and encouragement from Egypt. The revolt began when Datames, satrap of Cappadocia (l. c. 407-c.362 BCE), was chosen by Artaxerxes II to lead a campaign against Egypt. Egypt had been taken by the Persians under Cambyses II in 525 BCE but had thrown off Persian rule, at least of the Delta region, by 411 BCE. Campaigns were mounted periodically from then on to reclaim the lost territory and Datames was in command of the 372 BCE expedition.

Feeling he was unappreciated at Artaxerxes II's court, and feeling poorly used, Datames accepted the support the Egyptian pharaoh Nectanebo I (r. c. 379-363 BCE) and turned on Artaxerxes II. He was defeated and killed in 362 BCE, but his revolt continued under the satrap of Phrygia Ariobarzanes (d. 362 BCE) who had joined his revolt in 366 BCE in objection to what he saw as Artaxerxes II's arbitrary policies. He was betrayed by his son and crucified as a traitor in 362 BCE.

Many other satraps were involved in the revolt, for and against Artaxerxes II. One of the best-known of these is Mausolus, satrap of Caria (r. 377-353 BCE) who played both sides of the conflict but remained loyal to Artaxerxes II. At one point, claiming the forces of Artaxerxes II were marching against one of his cities, he requested funds from prominent citizens and rebel satraps to build a defensive wall. Once he had the money, he claimed that he had received word from the gods that the time was not right for building a wall and deposited the funds in his private treasury. Another time, he told the rebel satraps that he was unable to pay what was owed to the king and had bought time by promising to pay more in the near future, encouraging them to do the same. They followed his lead but were then forced to make good on their promise which covered the amount Mausolus owed and he wound up paying nothing (Olmstead, 415). He is most famous for his tomb, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world.

Seleucid & Parthian Satraps

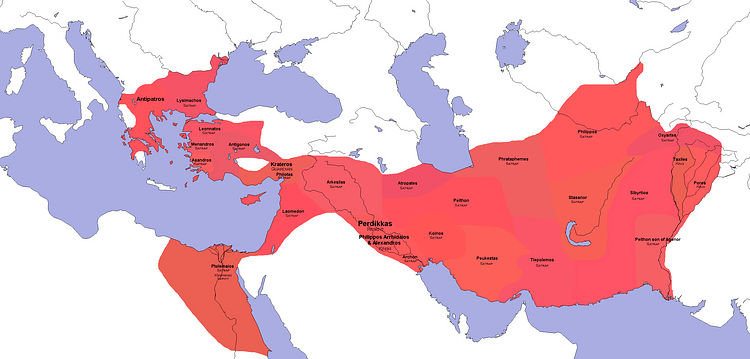

Although there were later revolts and conspiracies of the satraps, the Achaemenid Empire continued on more or less steadily. When the empire fell to Alexander the Great under the reign of Darius III (336-330 BCE), the satrapy system was still working well and was kept in place by the succeeding Seleucid Empire. The Seleucid Empire was founded by one of Alexander's generals, Seleucus I Nicator (r. 305-281 BCE), who initially had to campaign to consolidate his reign but then held the satraps he appointed in place through the Achaemenid model of government.

After his death, various satrapies rose in revolt and his successor, Antiochus I Soter (r. 281-261 BCE) enlisted the services of the Celts of Galatia as mercenaries to put them down and bring the regions back under his control. One of the objections of the people under Seleucid rule was that the Seleucid kings – of Macedonian-Greek lineage – favored Greeks and appointed them as satraps. Greek became the language of the court and satraps were encouraged in Hellenizing their regions. Alexander had tried to blend Persian and Greek cultures and Seleucus I continued this policy but not all of his satraps – or those of his successors – were interested in pursuing the same.

One example of this is the satrap Andragoras of Parthia (d. 238 BCE) who was appointed under the reign of Antiochus I Soter or, more likely, his successor Antiochus II Theos (r. 261-246 BCE). He is referenced as an Iranian satrap who was either assigned or took the Greek name Andragoras upon his appointment. Little is known of him until his rebellion under the reign of Seleucus II Callinicus (r. 246-225 BCE) when he declared Parthia an independent kingdom in 245 BCE shortly after Arsaces I of the Parni tribe broke Parthia away from the Seleucid Empire in 247 BCE. Andragoras tried to retain his hold on the kingdom as Arsaces I rose in power but was killed in 238 BCE as the Parthian Empire rose under Arsaces I's reign (247-217 BCE). Arsaces I expanded his territory, capitalizing on the Seleucid Empire's various distractions, and his successors would continue this policy, especially after the Seleucid defeat by Rome at the Battle of Magnesia in 190 BCE and the humiliating Treaty of Apamea of 188 BCE, which cost the Seleucids most of their empire.

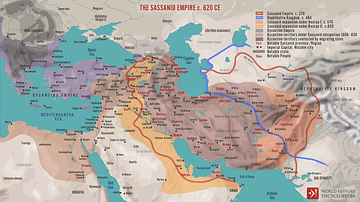

The Parthians also kept the Achaemenid satrapy system but allowed a looser confederation with less emphasis on the central government. Client kings (also known as vassal kings) were allowed to retain their positions and appointed satraps were given greater freedom in making and enforcing policy. The Parthian Empire was divided into Upper Parthia and Lower Parthia, comprised of five regions then divided into provinces. These provinces were allowed to act fairly freely without regard to the dictates of the central government and this eventually led to the empire's downfall when one of the vassal kings, Ardashir I (r. 224-240 CE) rebelled against the Parthian king Artabanus VI (r. 213-224 CE), defeating him and founding the Sassanian Empire.

Sassanian Satrapy

Ardashir I also kept the Achaemenid model after consolidating the fractured regions of the Parthian Empire. He emphasized a strong central government and appointed satraps (known as Shahrabs) of his own choosing to the different provinces. The major difference between the Sassanian system and the Achaemenid was the elevation of the religion of Zoroastrianism. The prophet and visionary Zoroaster (also known as Zarathustra) received his revelation and developed the religion at some point between 1500-1000 BCE and, while it is unclear whether Cyrus the Great was an adherent, it was the religion of his successors from Darius I onwards.

The Achaemenids did not make Zoroastrianism a part of their political platform, however, while the Sassanians did. Zoroastrianism became the state religion and satraps were expected to encourage its principles of the belief in a single supreme god named Ahura Mazda, the source of all good, and his eternal antagonist Ahriman (also known as Angra Mainyu), who was completely evil. Further, the meaning of life was to be found in choosing which of these deities one would serve and the recognition that human beings had free will to make this decision and then live with the consequences.

Zoroastrianism gave rise to a so-called heresy known as Zorvanizm which kept the basic belief system of the mother religion but claimed that both Ahura Mazda and Ahriman had been created by Zorvan (time) and so were brothers and created beings. All human events were thus dictated by Zorvan, not Ahura Mazda, as all things happened in time and time ultimately held supreme power over one's life and death. Many Sassanian satraps were Zorvanites but, since this “heresy” was so close to Zoroastrianism it does not seem to have caused any problems. Shapur I (r. 240-270 CE), Ardashir I's son and successor, was most likely a Zorvanite and had the visionary Mani (l. 216-274 CE), founder of Manichaeism, as a guest at his court.

The Sassanian Empire is considered the height of ancient Persian culture and a significant aspect of its success was its policy of religious tolerance. Satraps were encouraged to welcome people of all faiths and so Jews, Christians, Buddhists, and any others were allowed to build houses of worship throughout the empire and practice their faith freely. This policy, which was central to the Achaemenid government, may have been as successful as it was under the Sassanians because of the Zorvanite insistence on time – a nebulous concept – as the supreme arbiter of life and death rather than a specific deity with a certain agenda.

The Sassanian Empire fell to the invading Muslim Arabs in 651 CE and, although the basic form of the satrapy system would be retained, religious tolerance was rejected in favor of a policy of conversion and, eventually, taxation of non-Muslims. The Persian system was continued by the post-Muslim dynasties of the Safavids, Afshars, Zands, and the Qajar from c. 1501-1925 CE and, by the time of the earliest of these, had already influenced the development of the Roman government, the nascent European states of Late Antiquity, and would continue to impact other governmental systems up to the present day.