According to legend, Ancient Rome was founded by the two brothers, and demigods, Romulus and Remus, on 21 April 753 BCE. The legend claims that in an argument over who would rule the city (or, in another version, where the city would be located) Romulus killed Remus and named the city after himself. This story of the founding of Rome is the best known but it is not the only one.

Other legends claim the city was named after a woman, Roma, who traveled with Aeneas and the other survivors from Troy after that city fell. Upon landing on the banks of the Tiber River, Roma and the other women objected when the men wanted to move on. She led the women in the burning of the Trojan ships and so effectively stranded the Trojan survivors at the site which would eventually become Rome. Aeneas of Troy is featured in this legend and also, famously, in Virgil's Aeneid, as a founder of Rome and the ancestor of Romulus and Remus, thus linking Rome with the grandeur and might which was once Troy.

Still other theories concerning the name of the famous city suggest it came from Rumon, the ancient name for the Tiber River, and was simply a place name given to the small trading center established on its banks or that the name derived from an Etruscan word which could have designated one of their settlements.

Early Rome

Originally a small town on the banks of the Tiber, Rome grew in size and strength, early on, through trade. The location of the city provided merchants with an easily navigable waterway on which to traffic their goods. The city was ruled by seven kings, from Romulus to Tarquin, as it grew in size and power. Greek culture and civilization, which came to Rome via Greek colonies to the south, provided the early Romans with a model on which to build their own culture. From the Greeks they borrowed literacy and religion as well as the fundamentals of architecture.

The Etruscans, to the north, provided a model for trade and urban luxury. Etruria was also well situated for trade and the early Romans either learned the skills of trade from Etruscan example or were taught directly by the Etruscans who made incursions into the area around Rome sometime between 650 and 600 BCE (although their influence was felt much earlier). The extent of the role the Etruscan civilization played in the development of Roman culture and society is debated but there seems little doubt they had a significant impact at an early stage.

From the start, the Romans showed a talent for borrowing and improving upon the skills and concepts of other cultures. The Kingdom of Rome grew rapidly from a trading town to a prosperous city between the 8th and 6th centuries BCE. When the last of the seven kings of Rome, Tarquin the Proud, was deposed in 509 BCE, his rival for power, Lucius Junius Brutus, reformed the system of government and established the Roman Republic.

War & Expansion

Though the city owed its prosperity to trade in the early years, it was the Roman warfare which would make it a powerful force in the ancient world. The wars with the North African city of Carthage (known as the Punic Wars, 264-146 BCE) consolidated Rome's power and helped the city grow in wealth and prestige. Rome and Carthage were rivals in trade in the Western Mediterranean and, with Carthage defeated, Rome held almost absolute dominance over the region; though there were still incursions by pirates which prevented complete Roman control of the sea.

As the Republic of Rome grew in power and prestige, the city of Rome began to suffer from the effects of corruption, greed and the over-reliance on foreign slave labor. Gangs of unemployed Romans, put out of work by the influx of slaves brought in through territorial conquests, hired themselves out as thugs to do the bidding of whatever wealthy senator would pay them. The wealthy elite of the city, the patricians, became ever richer at the expense of the working lower class, the plebeians.

In the 2nd century BCE, the Gracchi brothers, Tiberius and Gaius, two Roman tribunes, led a movement for land reform and political reform in general. Though the brothers were both killed in this cause, their efforts did spur legislative reforms and the rampant corruption of the Roman Senate was curtailed (or, at least, the senators became more discreet in their corrupt activities). By the time of the First Triumvirate, both the city and the Republic of Rome were in full flourish.

The Republic

Even so, Rome found itself divided across class lines. The ruling class called themselves optimates (the best men) while the lower classes, or those who sympathized with them, were known as the populares (the people). These names were applied simply to those who held a certain political ideology; they were not strict political parties nor were all of the ruling class optimates nor all of the lower classes populares.

In general, the optimates held with traditional political and social values which favored the power of the Senate of Rome and the prestige and superiority of the ruling class. The populares, again generally speaking, favored reform and democratization of the Roman Republic. These opposing ideologies would famously clash in the form of three men who would, unwittingly, bring about the end of the Roman Republic.

Marcus Licinius Crassus and his political rival, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great) joined with another, younger, politician, Gaius Julius Caesar, to form what modern historians call the First Triumvirate of Rome (though the Romans of the time never used that term, nor did the three men who comprised the triumvirate). Crassus and Pompey both held the optimate political line while Caesar was a populare.

The three men were equally ambitious and, vying for power, were able to keep each other in check while helping to make Rome prosper. Crassus was the richest man in Rome and was corrupt to the point of forcing wealthy citizens to pay him 'safety' money. If the citizen paid, Crassus would not burn down that person's house but, if no money was forthcoming, the fire would be lighted and Crassus would then charge a fee to send men to put the fire out. Although the motive behind the origin of these fire brigades was far from noble, Crassus did effectively create the first fire department which would, later, prove of great value to the city.

Both Pompey and Caesar were great generals who, through their respective conquests, made Rome wealthy. Though the richest man in Rome (and, it has been argued, the richest in all of Roman history), Crassus longed for the same respect people accorded Pompey and Caesar for their military successes. In 53 BCE he led a sizeable force against Parthia and was defeated at the Battle of Carrhae, in modern-day Turkey, where he was killed when truce negotiations broke down.

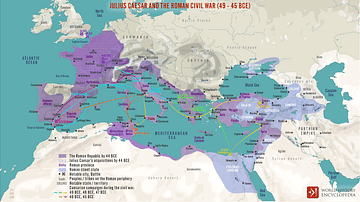

With Crassus gone, the First Triumvirate disintegrated and Pompey and Caesar declared war on each other. Pompey tried to eliminate his rival through legal means and had the Senate order Caesar to Rome to stand trial on assorted charges. Instead of returning to the city in humility to face these charges, Caesar crossed the Rubicon River with his army in 49 BCE and entered Rome at the head of it.

He refused to answer the charges and directed his focus toward eliminating Pompey as a rival. Pompey and Caesar met in battle at Pharsalus in Greece in 48 BCE where Caesar's numerically inferior force defeated Pompey's greater one. Pompey himself fled to Egypt, expecting to find sanctuary there, but was assassinated upon his arrival. News of Caesar's great victory against overwhelming numbers at Pharsalus had spread quickly and many former friends and allies of Pompey swiftly sided with Caesar, believing he was favored by the gods.

Towards Empire

Julius Caesar was now the most powerful man in Rome. He effectively ended the period of the Republic by having the Senate proclaim him dictator. His popularity among the people was enormous and his efforts to create a strong and stable central government meant increased prosperity for the city of Rome. He was assassinated by a group of Roman senators in 44 BCE, however, precisely because of these achievements.

The conspirators, Brutus and Cassius among them, seemed to fear that Caesar was becoming too powerful and that he might eventually abolish the Senate. Following his death, his right-hand man, and cousin, Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony) joined forces with Caesar's nephew and heir, Gaius Octavius Thurinus (Octavian) and Caesar's friend, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, to defeat the forces of Brutus and Cassius at the Battle of Phillippi in 42 BCE.

Octavian, Antony, and Lepidus formed the Second Triumvirate of Rome but, as with the first, these men were also equally ambitious. Lepidus was effectively neutralized when Antony and Octavian agreed that he should have Hispania and Africa to rule over and thereby kept him from any power play in Rome. It was agreed that Octavian would rule Roman lands in the west and Antony in the east.

Antony's involvement with the Egyptian queen Cleopatra VII, however, upset the balance Octavian had hoped to maintain and the two went to war. Antony and Cleopatra's combined forces were defeated at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE and both later took their own lives. Octavian emerged as the sole power in Rome. In 27 BCE he was granted extraordinary powers by the Senate and took the name of Augustus, the first Emperor of Rome. Historians are in agreement that this is the point at which the history of Rome ends and the history of the Roman Empire begins.