The three Anglo-Maratha Wars (1775-1819) were fought between the Maratha Confederacy of India (aka the Mahrattas, 1674-1818) and the British East India Company (EIC). The Maratha Hindu princes were rarely unified, and so the EIC steadily reduced their power through a blend of diplomacy and warfare, which led to ultimate victory and the dissolving of the confederacy.

There were three Anglo-Maratha Wars between the East India Company and the Maratha Confederacy:

- First Anglo-Maratha War (1775-1782)

- Second Anglo-Maratha War (1803-1805)

- Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817-1819)

East India Company Expansion

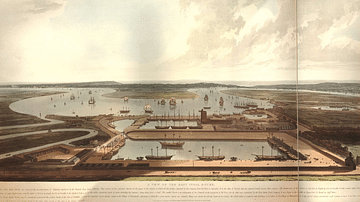

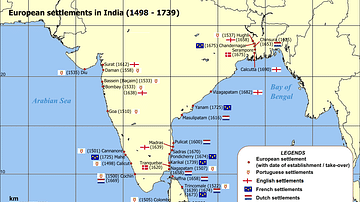

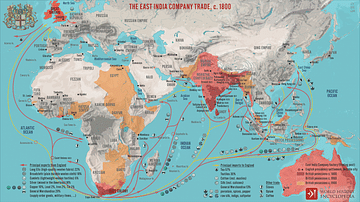

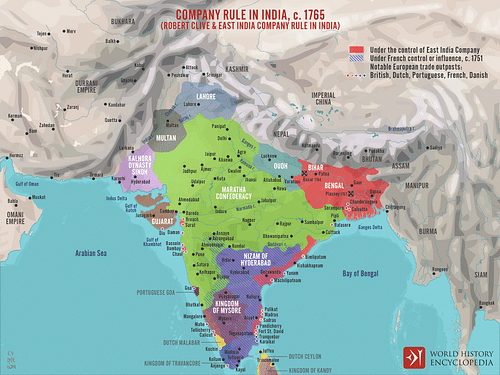

The East India Company was founded in 1600, and by the mid-18th century, it was benefiting from its trade monopoly in India to make its shareholders immensely rich. The Company was effectively the colonial arm of the British government in India, but it protected its interests using its own private army and hired troops from the regular British army. By the 1750s, the Company was keen to expand its trade network and begin a more active territorial control in the subcontinent.

Robert Clive (1725-1774) won a famous victory for the EIC against the ruler of Bengal, Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah (b. 1733), at the Battle of Plassey in June 1757. The Nawab was replaced by a puppet ruler, the state's massive treasury was confiscated, and the systematic exploitation of Bengal's resources and people began. The EIC won another key contest in October 1764 with victory at the Battle of Buxar (aka Bhaksar) against the Mughal emperor Shah Alam II (r. 1760-1806). The emperor then awarded the EIC the right to collect land revenue (dewani) in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. This was a major development and ensured the Company now had vast resources to expand and protect its traders, bases, armies, and ships.

Unfortunately for the EIC, its growth meant that it came into conflict with new powers, chief amongst them the southern state of Mysore and the Maratha Confederacy. A third major power in southern India was the Nizam of Hyderabad, the largest princely state in India but rarely effective in military terms. The competition for territorial control between these four powers led to a complex game of empires that involved multiple wars and endlessly shifting alliances of convenience. Ultimately, the EIC was the victor, but it first had to fight four Anglo-Mysore Wars (1767-1799) against the Kingdom of Mysore and three Anglo-Maratha Wars.

The Maratha Confederacy

The Maratha Confederacy was a loose alliance of various independent Hindu princes. They acquired the name (in use from the 17th century) from the region they ruled, Maharashtra. This region was composed of "rocky hills and jungle-covered valleys lying on the western side of the Deccan" (Heathcote, 13).

The first great ruler was Shivaji (r. 1674-1680), who took the royal title Chatrapati. Shivaji's grandson Shahu (r. 1708-1748) created the title of Peshwa, effectively the supreme or executive leader of the confederacy, a position which became hereditary. The Peshwa was based at Poona (Pune), but the rulers of the various Maratha states were only nominally under his sovereignty.

The Maratha Confederacy had challenged and conquered territories of the Mughal Empire (1526-1857) in the southern and western areas of India through the 18th century and was potentially the most formidable military power in the region when unified. The problem for the Marathas was that they rarely worked collaboratively to meet a common enemy. One thing that did unite them was a threat from another religion, particularly Islam.

Eventually, the Marathas controlled a vast swathe of central India to Orissa in the east and Delhi in the north. This expansion meant their southern and eastern borders encroached on territory under the covetous gazes of Mysore and the EIC, respectively. In addition, the northern frontier of the Maratha Empire brought it into frequent conflict with Afghan rulers such as Ahmad Shah Abdali (1722-73), who seriously weakened the Marathas with his victory at the Battle of Panipat on 13 January 1761. From this date, the Maratha Confederacy consisted of the Peshwa of Poona and the rulers of the Indian princely states of Gwalior, Indore, Berar, and Baroda, all hereditary monarchs. Sometimes these rulers competed with each other for resources and territory. Feuds between ruling Maratha families were common. The indiscriminate raiding of non-Maratha territories made them unpopular with all of their neighbours.

The Marathas might well have replaced the crumbling Mughal Empire as the primary power in India, but their lack of unity, their inability to convince the Hindu desert warriors, the Rajput chiefs, to join them, and their military reversals to the Afghans prevented this ambition from being realised. The Marathas were also unpopular because of their policy of extracting a one-quarter tax on revenue, the chauth, wherever they dominated. Still a formidable power, the Marathas would prove to be both a help and hindrance to the various rival powers jostling for control of India.

Maratha Warfare

The Marathas were certainly adept at warfare, using light cavalry and light artillery pieces to quickly move armies when required for an offensive and hillforts when defence was necessary. A weakness was their inferior training and artillery compared to the EIC (and Mysore), but they did improve in these areas over time thanks to training from European mercenaries (typically French and British), which ensured they kept apace with the latest military developments. The Marathas learnt to use artillery so well that it became a formidable obstacle to EIC victories in the field. Another feature of Maratha armies was that it was not uncommon for women to fight using matchlocks, swords, and as cavalry riders.

First Anglo-Maratha War (1775-1782)

From 1767 to 1769, the EIC was involved in the First Mysore War. Haidar Ali (1721-1782) had taken over the Kingdom of Mysore in 1761, and intent on expanding his territory, he declared war on the EIC in 1767. With 50,000 well-trained and well-equipped troops, including camel cavalry that fired rockets, Ali was a formidable opponent, and he ensured the Marathas did not join in the fighting by buying them off with a huge quantity of silver. The indecisive First Mysore War (1767-69) ended in a treaty which included a mutual protection clause against any future threat from the Marathas.

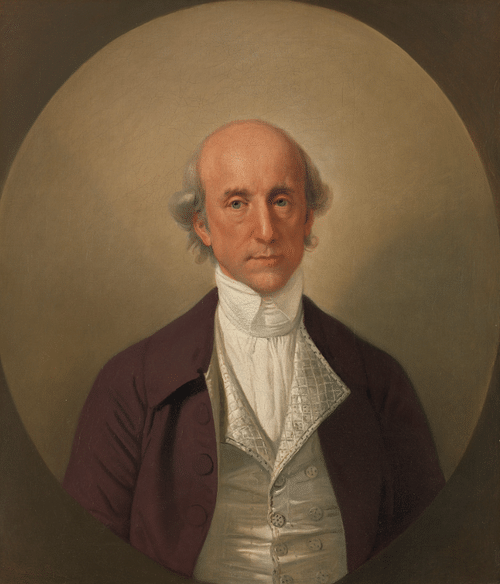

In 1774, Warren Hastings (1732-1818) was appointed the Governor-General of the East India Company, a position he would hold until 1785. After several years of skirmishes, in 1778, the East India Company attacked the Maratha Confederacy directly but was defeated at the battle of Wadgaon near Poona in January 1779. The Marathas had cut off the EIC army's supply lines and all but surrounded the enemy force, obliging the British to retreat after having thrown away their heavy cannons in the pool of a Hindu temple. A series of battles ensued over the next three years, with the victors alternating in an evenly-matched contest.

The First Anglo-Maratha War ended inconclusively with a fudged compromise, the May 1782 Treaty of Salbai, which at least brought peace between the two sides. The terms of the treaty only meant that, sooner or later, the EIC and Marathas would lock horns in battle again. It was a wasted opportunity for the Marathas since if they had pressed on with the war, they might well have got the better of the EIC, which was at the time crippled with debts and facing enemies elsewhere. In the event, the treaty secured a lengthy period of peace with the Marathas, which permitted the EIC to recover and expand elsewhere, particularly regarding the ongoing war with Mysore, the Second Anglo-Mysore War (1780-84).

Second Anglo-Maratha War (1803-1805)

In the decade leading up to the Second Anglo-Maratha War, the EIC had been busy subduing the Kingdom of Mysore in two more wars: 1790-92 and 1799. The Marathas even contributed 12,000 men (light cavalry) to fight for the EIC. The Mysore ruler, Tipu Sultan (aka Tipoo Sahib, r. 1782-1799), had been defeated and killed, and the kingdom was effectively taken over by the EIC, which installed a young puppet ruler. The EIC was now free to concentrate on the Marathas once again.

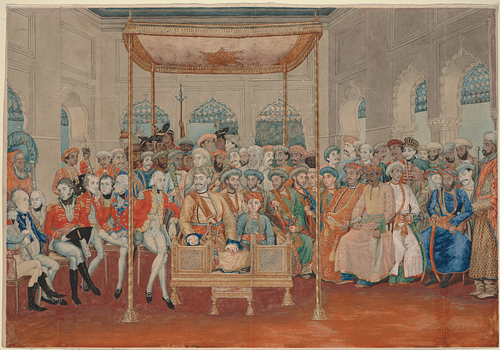

In the EIC's long and successful strategy of combining diplomacy, intrigue, and military might, the 1802 Treaty of Bassein had already made the Peshwa, Baji Rao II (r. 1796-1818), a subsidiary ally of the EIC, and he was awarded a pension. Rao had been evicted from his own capital by rival Marathas, and this was the price for EIC backing and his restoration to power. By 1805, the rulers of Gwalior and Indore had also signed subsidiary alliances, but after learning that they and the Peshwa were obliged to permit an EIC resident at his court and pay for the garrisoning of EIC troops in their territory, two of the remaining Maratha rulers decided to fight for their independence in a conflict that has become known as the Second Anglo-Maratha War. The two rulers who fought the EIC were Daulat Rao Sindhia (1779-1827) and Raghuji Bhonsle II (d. 1816). A third Maratha ruler, Jaswant Rao Holkar (1776-1811), stayed neutral in the hope the others and the EIC would weaken each other in a long war, a situation he could then take advantage of.

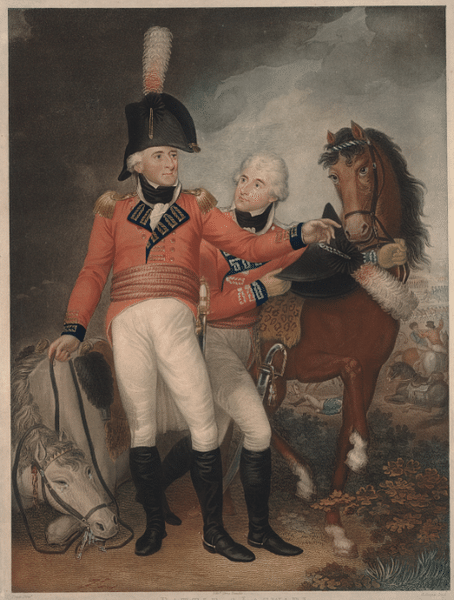

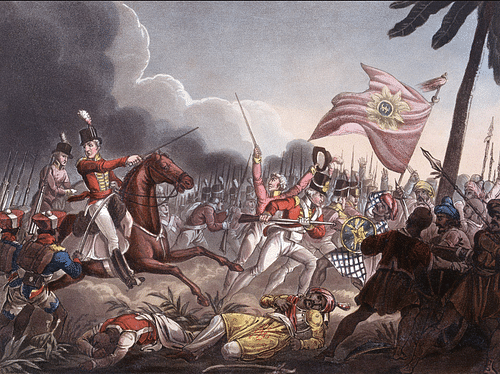

At the Battle of Assaye on 23 September 1803, General Sir Arthur Wellesley (1769-1852, the future Duke of Wellington) masterminded victory for the EIC over the Maratha army of Daulat Rao Sindhia, head of the Gwalior state. The cause was greatly helped by Wellesley first steadily building up supplies and then bribing British and Anglo-Indian mercenary officers in the Marathas' employ not to fight. When the Marathas heard of this subterfuge, they promptly dismissed all their European officers believing them all of suspect loyalty. The unfortunate consequence for the Marathas was that their army now had no command structure and was routed, but not before their artillery had caused tremendous damage to the British. The costs for the EIC victory in this bloody battle were high, with around one-third of its army killed or wounded. 6,000 Maratha soldiers were killed at Assaye. The experienced British officers were all in agreement that the Maratha artillery was as well organised and deadly as that of any European army they had ever faced. There was some consolation for the human losses in the capture of 98 Maratha cannons. Wellesley then won another battle at Argaum (aka Argaon) in November 1803, but at the end of his career and even after defeating Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) at Waterloo in June 1815, Wellesley declared that his greatest ever military challenge had been at Assaye.

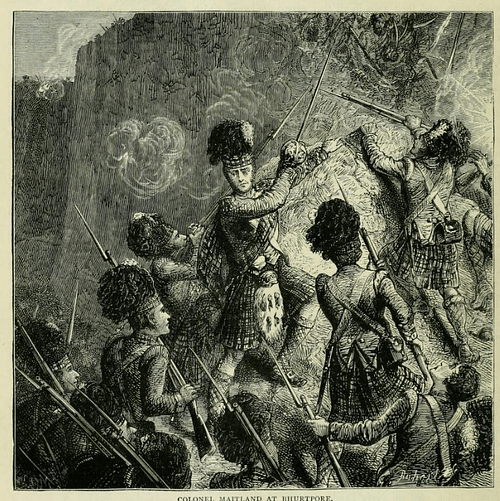

On 1 November 1803, the EIC won another decisive victory at the Battle of Laswari, this time with a force of 10,000 men under the able command of General Gerard Lake (1744-1808), a veteran of the American War of Independence. Again, the costs of victory were high, with around 838 EIC troops killed or wounded. The EIC then took over Delhi and its surrounding territory. There were a few minor Maratha successes, such as the defence of Bhurtpore (aka Bharatpur) against multiple British attacks in early 1805, but with the large losses in central India to Wellesley and in northern India to Lake, the Maratha Confederacy was now but a shadow of its former self. The Hindu princes were largely obliged to follow EIC policies and put up with a permanent resident backed by sepoys (EIC Indian troops). However, there would be one more conflict to come in a doomed effort to regain the Marathas' lost independence.

Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817-1819)

Between 1814 and 1816, the EIC was busy in the north of the subcontinent where it won the Anglo-Nepalese War (aka Gurkha War). Then, in 1817, the EIC turned its attention southwards again. The Marathas were not at all happy with the level of political interference the EIC was orchestrating in central India while, on the other side, the EIC was growing tired of bands of Pindaris (raiders supposed to be under the control of the Marathas) looting what it considered its property. By now, the EIC had the largest army in Asia – some 113,000 men were mobilised – and when it formally declared war on the Maratha Confederacy, its fate was sealed.

The Third Anglo-Maratha War, also known as the Pindari War, saw Baji Rao II defeated by an EIC army at the Battle of Kirki (aka Kirkee or Khadki) on 5 November 1817 and again at the Battle of Koregaon on 1 January 1818. As to the two remaining Maratha princes, the Raja of Nagpur lost the Battle of Sitabaldi on 27 November 1817 and another on 16 December, this time outside Nagpur. The EIC then defeated Malhar Rao Holkar III (r. 1811-1833) at the Battle of Mahidpur (aka Mahdipore) on 20 December 1817. Superior numbers, training, discipline, and the lack of loyalty in the opposition were all reasons for the EIC victories, as the historian L. James here summarises:

…many Marathas and Pindaris defected, lured into the Company's army by the prospect of higher wages, paid regularly. A new pattern of war was emerging: the Company divided, conquered and then recruited. (73)

After this third war, the Maratha Confederacy ceased to exist as the EIC now controlled Gujarat, Maharastra, Rajasthan, and Berar. Consequently, Baji Rao II was the last Peshwa of the Marathas, but at least he received a generous pension until 1853. The Maratha princes were obliged to sign the familiar subsidiary alliance the EIC imposed on the vanquished, leaving them only in control of minor domestic affairs. The EIC was now the sole great power in India. Many of the Marathas did not forget the wars and rose against the EIC in the infamous but failed rebellion of 1857-8, known as the Sepoy Mutiny or The Uprising against British colonial rule in India. This rebellion led to the British government taking over the territories of the EIC, and so the British Raj (rule) of India began.