The Anglo-Powhatan Wars were a series of conflicts between the English colonists of Virginia and the indigenous people of the Powhatan Confederacy between 1610-1646 CE. The Powhatan Confederacy (of over 30 tribes) was led by the chief Wahunsenacah (l. c. 1547 - c. 1618 CE) when Jamestown Colony of Virginia was established by the English in 1607 CE.

Wahunsenacah (also known as Chief Powhatan) at first thought the English could be valuable allies against Spanish raids and hostile Native American tribes, but relations between the Powhatan Empire and English deteriorated as the colonists demanded more land, especially after 1610 CE when the English began cultivating tobacco.

All three wars (also given as the Powhatan Wars) were won by the English as they resulted in further loss of land for the Native Americans and greater restrictions placed upon them. Although hostilities broke out before and after the official dates of the wars, the generally accepted dating is:

- First Powhatan War: 1610-1614 CE

- Second Powhatan War: 1622-1626 CE

- Third Powhatan War: 1644-1646 CE

The third war ended when the Powhatan chief, Opchanacanough (l. 1554-1646 CE), who had succeeded Wahunsenacah, was killed after being taken captive and his successor, Necotowance (l. c. 1600-1649 CE), signed a peace treaty which effectively dissolved the Powhatan Confederacy. Necotowance was succeeded by his son, Totopotomoi (l. c. 1615-1656 CE) who ruled only over his own tribe of the Pamunkey and greatly diminished lands. He was succeeded by his wife, Cocacoeske (l. c. 1640-1686 CE) who held even less power and fewer lands, especially after Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676 CE which led to the Treaty of Middle Plantation in 1677 CE and the indigenous people’s loss of almost all of their traditional lands.

Powhatan Confederacy & the Land

The region of modern-day Virginia, USA, was known by the indigenous inhabitants as Tsenacommacah (densely populated land or densely inhabited land) prior to the arrival of the English. There were over 30 different native tribes throughout the area, which were brought under the control of the Powhatans c. 1570 CE by Wahunsenacah.

Originally, there were six tribes under his rule – his own, the Powhatan, the Appamattuck, Arrohateck, Chiskiack, Mattaponi, and Pamunkey. Wahunsenacah expanded his empire by killing the chiefs of other tribes and appointing his sons, or trusted relatives, in their place. These tribes paid tribute to Wahunsenacah in return for peace and protection from others outside of the confederacy, notably the Iroquois who had also formed a powerful confederacy by this time.

Each tribe under Wahunsenacah had its own chief and council of elders but were subordinate to him. They considered Tsenacommacah their ancestral home, given to them by their gods Ahone, the Creator, and Oke, the helper who participated in the people’s daily life. The land was intimately linked to these deities and the rituals enacted asking for help or thanking them needed to be performed at certain places within this territory. Further, by the early 17th century CE, the indigenous people had been living in the region for over 12,000 years and had been interring their dead in the land throughout that time. The land was also, therefore, associated with rituals honoring their ancestors as this was an integral aspect of Native American religion and culture.

The people were also linked to the crops they cultivated and those that grew wild. Scholar David J. Silverman comments:

Edible crops had female spirits and therefore should be tended by females, unlike tobacco, which had a male spirit and was the sole plant raised by males. Many Native peoples east of the Mississippi have traditions of a woman, a Corn Mother, visiting the people in ancient times to teach them how and where to plant maize, beans, and squash, thereafter called the Three Sisters. (44)

Wahunsenacah’s empire stretched from modern-day Virginia through North Carolina and, although there were permanent settlements, crop rotation and the migration of various animals pursued in hunting meant some seasonal sites and a semi-nomadic lifestyle at certain times in the year. All of these activities, however, took place within Tsenacommacah which, c. 1607 CE, was inhabited by between 15,000-21,000 people.

Jamestown & the Powhatans

In 1607 CE, the English established the colony of Jamestown in a swampy region which the natives avoided because it was almost unusable. The expedition was manned by 100 English men and boys who had little to no experience in agriculture. Many were aristocrats who had never done any actual work, and it seems almost all of the new colonists were under the impression they need do very little upon arrival besides picking up the large deposits of gold they believed were to be found all over the land, free for the taking. When they found there was no gold and they would have to work the land to survive, they became discouraged and grew more so when they lost almost half their number to disease between May and September 1607 CE. Wahunsenacah had provided them with food but they still stole even more.

Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631 CE) finally took control of the colony, instituting the edict of "He that will not work, shall not eat" that motivated the colonists to fend for themselves, but they still continued the practice of stealing from their neighbors. Smith formed an alliance with Wahunsenacah while the commander of the expedition, Captain Christopher Newport (l. 1561-1617 CE), established boundaries between the settlement and native lands, but both underestimated the Powhatan chief, and neither understood that they were not dealing with some "ignorant savage" but with a refined and powerful, ruler. Scholar David A. Price comments:

What the English did not realize was that they were facing a tightly run, martially adept empire. Only gradually, over some months, would they come to understand the reach of Chief Powhatan’s power. (40)

It seems the colonists were still treating the natives as their food supply in 1609 CE. Smith had already met Wahunsenacah’s daughter Pocahontas (l. c. 1596-1617 CE) by this time and, at first, had established trust between the two people, but the continual food shortage and neediness of the colonists strained the relationship. Smith returned to England in October 1609 CE and, by this time, his relations with the Powhatan were so poor that he did not even bother to tell them he was leaving.

In May of 1610 CE, more colonists arrived under Sir Thomas Gates (l. c. 1585-1622 CE), including John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622 CE) who brought with him tobacco seeds he hoped to cultivate in Virginia. Shortly after their arrival, Thomas West, Lord De la Warr (l. 1577-1618 CE) arrived and took control of colonist-native relations, instituting harsher policies of no compromise. Wahunsenacah had tried to deal fairly with the colonists, but as more land was now taken from him without compensation or respect, he ordered his warriors to attack the settlement, starting the First Powhatan War.

First Powhatan War

West demanded the Powhatans return tools and weapons the colonists had traded with them for food and Wahunsenacah replied that West and his people should leave and go back where they came from. West ordered Sir Thomas Gates to engage with one of the tribes, the Kecoughtans, and then sent two other commanders, James Davis (l. c. 1575-1623 CE) and George Percy (l. 1580-1632 CE), against the Paspaheghs in August of 1610 CE. Davis and Percy burned the Paspahegh capital, killing over 60 inhabitants, and kidnapped one of the chief’s wives and two of her children. The children were later thrown overboard and then shot on the trip back to Jamestown where their mother was executed.

Wahunsenacah responded with a counterattack, and West then sent Sir Thomas Dale (l. c. 1560-1619 CE) against the Arrohateck tribe, driving them from their lands and establishing the colony of Henricus north of Jamestown. The war was not a continuous engagement but a series of raids and counterraids. The English were used to formal battles in which antagonists faced each other on the field of battle and had to learn to counter and then employ guerilla warfare.

While the conflict wore on, more colonists arrived. John Rolfe’s tobacco crop was a financial success by 1612 CE, and this encouraged others to plant their own. Plantations for tobacco required more land and the influx of settlers cost the Powhatans even more. Wahunsenacah was not about to concede defeat and neither was West, but in 1613 CE, West became ill and returned to England. He turned over his position to Sir Samuel Argall (l. c. 1580-1626 CE) who maintained his policies.

In 1613 CE, Argall kidnapped Pocahontas and held her for ransom, first at Jamestown and later at Dale’s colony of Henricus. He demanded the return of captive colonists as well as the tools and weapons West had stipulated in 1610 CE. Wahunsenacah complied, but Argall refused to release Pocahontas. She remained a hostage at Henricus where she learned English and met John Rolfe, whose plantation was just across the river. In April 1614 CE, Pocahontas converted to Christianity, took the name Rebecca, and married John Rolfe at Jamestown. Their marriage was blessed both by Argall and Wahunsenacah and the First Powhatan War was brought to a close.

Peace of Pocahontas & the Second War

The marriage of Rolfe and Pocahontas established what became known as the Peace of Pocahontas (1614-1622 CE) during which the colonists and Powhatans cooperated with each other. Colonists compensated the Powhatans properly in land deals and refrained from stealing while the Powhatans ceased all hostilities and traded amicably with the colonists. In 1616 CE, John Rolfe, Pocahontas, and their young son, Thomas Rolfe (l. 1615 - c. 1680 CE) went on a promotional tour for the colony to England and, on the return trip, Pocahontas fell ill and died in 1617 CE. Thomas was left in England with Rolfe’s brother.

Wahunsenacah had sent a number of his people along on the trip to bring him back news of the English in their own land. One of these was his sage (and Pocahontas' brother-in-law) Tomocomo, who, upon his return, denounced the English and said they could not be trusted. English reports claim that Tomocomo’s charges were denounced before a Powhatan council by the colonists and that he was shamed into silence, but this account is not universally accepted, and later events strongly suggest Tomocomo’s words influenced the Powhatan council far more than the colonists’ defense.

Wahunsenacah had stepped down as chief in 1617 CE and was succeeded by his half-brother Opchanacanough. It was formerly believed that Opchanacanough launched the Second Powhatan War in response to the killing of his war chief, Nemattanew, in 1621 CE but this claim has been discredited. It is now generally accepted that Opchanacanough had been planning his attack long before Nemattanew was killed.

One of the stated goals of the colonists was the conversion of the natives to Christianity and the success of Pocahontas’ conversion encouraged efforts to reach more of the indigenous people. Opchanacanough took advantage of this policy, sending warriors to, allegedly, seek conversion and even did so himself. The Peace of Pocahontas was still in observance and the colonists seem to have believed the natives were sincere in their interests in conversion, so no defensive measures were in place.

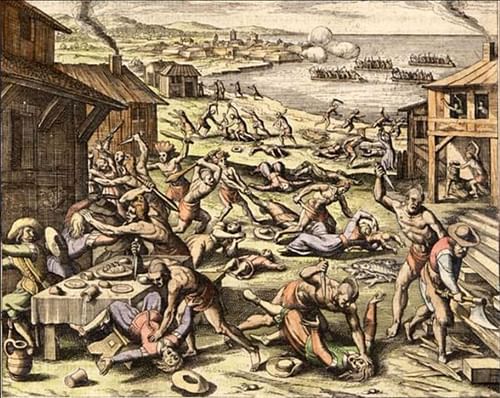

On 22 March 1622 CE, Opchanacanough launched the attack which came to be known as the Indian Massacre of 1622 CE, killing over 300 colonists and destroying a number of settlements, including Henricus. Jamestown itself was only spared because it was able to raise a defense after it was warned by a young Powhatan boy. The entire action took place in a single day and, when it was over, Opchanacanough withdrew back to his own lands and waited for a response.

He seems to have hoped that the overwhelming destruction and death would be enough to discourage the English from continued colonization. This proved to be a vain hope, however, and so the Second Powhatan War was begun. This conflict followed the same pattern as the First Powhatan War with each side winning small victories but nothing conclusive. Opchanacanough never was able to mount another offensive like the March 1622 CE massacre, and the colonists found themselves fighting a guerilla war of attrition against an enemy who could strike and disappear instantly. The colonists’ muskets were not as effective as the Powhatan bows and arrows and, further, the natives simply knew the land better and could ambush their enemy at will.

Since the colonists could not succeed in battle, they resorted to trickery in 1623 CE. They asked to meet the Powhatans for a peace treaty but poisoned the drinks they offered at the meeting and then slaughtered the Powhatan delegation. This time, it was the Powhatans who were caught off guard and unprepared and the colonial militia burned the villages of a number of tribes, slaughtering as many natives as they could find. The conflict officially ended in 1626 CE when Opchanacanough sued for peace, but hostilities continued, on and off, until 1629 CE.

The Palisade Peace & Third Powhatan War

To prevent further problems, the colonists built a palisade to form a stockade wall between them and the Powhatans. Made of wood, it stretched 6 miles (9 km) across the Virginia Peninsula. William Berkeley (l. 1605-1677 CE) became governor of Virginia in 1641 CE and encouraged further tobacco cultivation by staking himself out a large plantation.

By this time, Rolfe’s product had become so popular worldwide that tobacco was Virginia’s chief crop, and, in order to harvest it faster for greater profit, Africans were imported as slaves to work the fields. Tobacco was a labor-intensive crop and so more and more slaves were needed and this meant more land to house them, more land for the growing number of plantations, more land for the influx of settlers drawn by the promise of wealth.

By 1644 CE, the English colonists outnumbered the remaining Powhatan in the region, and Opchanacanough, though nearly 90 years old, launched another attack in an attempt to drive them from his lands. He broke through the palisade with every warrior he could muster and killed between 400-500 colonists in a brutal surprise raid, launching the Third Powhatan War. Again, Opchanacanough did not press his advantage but returned to his lands to see what the colonists would do. The colonists, just as they had done earlier, fortified their defenses and then struck back.

In 1645 CE, Berkeley led a major attack on Opchanacanough’s capital, killing most of his warriors and capturing the chief himself who was led back to Jamestown in chains. The Powhatan survivors of the attack, and all others who could be caught, were sold into slavery. Opchanacanough was caged in Jamestown and displayed for visitors as a curiosity until he was shot in the back by his guard, against orders from Berkeley, in 1646 CE. The chief’s death ended the Third Powhatan War, and peace was formalized by the signing of the Treaty of 1646 between Opchanacanough’s successor Necotowance and Governor Berkeley.

Conclusion

The Treaty of 1646 dissolved the Powhatan Confederacy and conferred most of their land to the colonists. Necotowance was chief of the confederacy in name only since most of the indigenous people who had been living in the region c. 1607 CE were now dead either from disease or through conflict, sold into slavery in the West Indies, or had fled the region and joined with other tribes elsewhere. Totopotomoi, Necotowance’s successor, was only chief of two tribes, and his successor, his wife Cocacoeske, only presided over the Pamunkey tribe.

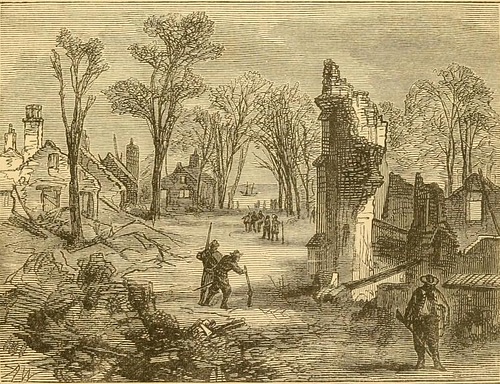

Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676 CE, during which indentured servants and landowners of the interior attacked the remaining native villages as well as Jamestown itself, killed off more of the indigenous people. Jamestown was burned and the government moved to another colony known as Middle Plantation (present-day Williamsburg) where the Treaty of Middle Plantation was signed 28 May 1677 CE under the new governor Sir Herbert Jeffreys.

The treaty stipulated reservations for the remaining Native Americans, where they were guaranteed the right to bear arms, conduct trade freely, and hunting and fishing rights to their ancestral lands as long as they lived in peace with the colonists. Cocacoeske had convinced the other remaining chiefs in the region to sign, and the indigenous people were confined to small areas of their ancestral lands which then grew even smaller as the Virginia government encouraged colonists to take even more land on their own initiative.

In the present day, the only two tribes in Virginia that still maintain their original reservations are the Mattaponi and Pamunkey. The Racial Integrity Act of 1924 CE denied them official existence as it mandated that everyone in Virginia be classified as either “white” or “colored” and the Mattaponi and Pamunkey did not consider themselves as either white or black, nor did they fit the official designation.

They petitioned the Virginia government for recognition as early as the 1950s CE and were recognized as Native American tribes in the 1960s CE, but this was only by Virginia, not the Federal Government of the USA. It was not until 2018 CE that the Mattaponi and Pamunkey were recognized by the Federal Government as the original people of the land once known as Tsenacommacah.