The Antinomian Controversy (1636-1638 CE) was a religious-political conflict which divided the Massachusetts Bay Colony of New England in the 17th century CE. The disagreement, also known as the Free Grace Controversy, centered on the primacy of God's grace over good deeds or as the preeminence of a Covenant of Grace over a Covenant of Works.

The antagonists were John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649 CE), governor of the colony, aligned with other magistrates including John Cotton (l. 1585-1652 CE) and Thomas Dudley (l. 1576-1653 CE), among others, and the dissenters Anne Hutchinson (l. 1591-1643 CE), John Wheelwright (l. c. 1592-1679 CE) and, in the early stages, then-governor Sir Henry Vane (l. 1613-1662 CE). All of these individuals were Puritan Christians who recognized the primacy of the doctrine of God's free grace; the dispute never questioned this directly and was actually about the challenge to the Boston magistrates' civil authority over religious matters and the colony's unity of vision.

The Antinomian Controversy (antinomian from the Greek "against the law") ended with the banishment of Anne Hutchinson in 1638 CE. Wheelwright had been banished the year before and Henry Vane had returned to England that same year (1637 CE). After Hutchinson was expelled, another religious dissenter, Roger Williams (l. 1603-1683 CE), who had been banished in early 1636 CE, began a literary duel with John Cotton over religious freedom and persecution which addressed a number of points raised by the Antinomian Controversy.

The argument was never definitively won by either side. Cotton continued to argue for the importance of the covenant of works and defended the practice of religious persecution of dissenters while Williams championed religious tolerance and liberty of conscience in his new colony of Providence just as Hutchinson and the others did in theirs. The dispute would eventually inform the decision of the Founding Fathers to separate church from state in the formation of the United States government.

Unity in the Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was founded on the vision of John Winthrop's sermon, A Model of Christian Charity, delivered in 1630 CE either before he and his party left England or en route to North America aboard the ship Arbella. Winthrop led 700 Puritans in four ships on this expedition and made clear that they were on a holy mission from God. God and the colonists had formed an agreement, a covenant, which the colonists needed to honor completely to receive God's blessings; otherwise, they would be deserving of his wrath.

Honoring the covenant hinged on unity of vision, Winthrop explained, in order to make the colony "a city upon a hill", a model Christian community, which would serve as an example to the world. The Puritans were so-called because they wanted to 'purify' the Anglican Church of Catholic elements. Since the monarch of England was head of the Church, however, any criticism of it was considered treason, and Puritans were persecuted. Those Puritans who felt the Church was too corrupt to be purified were known as separatists, and a separatist congregation had been part of the expedition which successfully founded Plymouth Colony in 1620 CE. Winthrop's colony was founded ten years later but on a different model and that model demanded conformity.

The Plymouth Colony was made up of separatists and Anglicans who had made the transatlantic voyage together aboard the Mayflower and formed a democratic government through the Mayflower Compact which addressed the concerns of both groups. Massachusetts Bay Colony was founded entirely by Puritans, and although its government appeared to be a democratic Republic, it was actually a theocracy because no official would be elected who did not support Winthrop's vision of a single true understanding of Christianity and its practice. Everyone in the colony needed to adhere to this same vision, Winthrop maintained, because loss of unity threatened the covenant and the success of the colonists.

The Dissenters

The first well-known dissenter who challenged this vision was Roger Williams, who arrived at Boston in 1631 CE, came into conflict with the magistrates, and left for Plymouth Colony. Williams criticized the Bay colony as being too legalistic and closely aligned with the Anglican Church. He found Plymouth Colony just as legalistic and returned to the Bay colony to accept a position at the Salem church. He continued to share his opinions and criticisms of the Church of Boston and was finally banished in 1635 CE, narrowly escaping deportation back to England when he fled the colony in early 1636 CE.

John Cotton was a popular Puritan preacher in England who was forced to leave to avoid persecution in 1633 CE. He had been Anne Hutchinson's minister and, when he left for North America, Hutchinson and her family followed him to Boston, arriving in 1634 CE. She was at first well received by Winthrop who referred to her as a "goodly woman", but she resumed the practice of holding assemblies (known as conventicles) in her house, as she had in England, to study the Bible and discuss spiritual concerns, and these meetings would eventually form the basis of the charges against her. Like Cotton, Hutchinson emphasized the primacy of grace over works during her conventicles.

John Wheelwright, Hutchinson's brother-in-law, arrived after her and was also welcomed as a prominent preacher who was accepted as a member in good standing of the Boston Church. Cotton, Hutchinson, and Wheelwright all believed in the primacy of the covenant of grace over the covenant of works but, at first, phrased their views in conformity with the vision of the community which valued works as demonstrating God's grace in the life of a believer.

Sir Henry Vane was elected governor of the colony in 1636 CE and, according to Winthrop, fell under Hutchinson's "spell" and began to also advocate for the recognition of the importance of grace over works. Winthrop charged Vane with causing Cotton's "corruption" even though it is clear that Cotton held the same views before and after Vane's arrival, only changing them (or rephrasing them) during Hutchinson's trial. Winthrop seems to have considered Vane an especially dangerous threat to the colony as he was an aristocrat in a position of authority who was advocating views contrary to Winthrop's own.

Wheelwright's Sermon & the Petition

In December 1636 CE, the magistrates held a private meeting with Cotton and Hutchinson to discuss their differences in opinion regarding scripture and Hutchinson's practice of criticizing ministers whose views she rejected as anti-biblical. Nothing was resolved at this meeting, but Hutchinson's answers to questions, which she thought private, would later be used at her trial. Cotton seems to have defended Hutchinson at this meeting while also maintaining his good standing among the magistrates.

In January 1637 CE, Wheelwright was invited to preach a fast-day sermon, which was expected to emphasize penitence and humility but, instead, attacked those who supported a covenant of works. He claimed that those who believed works were evidence of justification before God were wrong and, further, led others astray from the true path of righteousness by causing them to believe that anything they did could warrant God's love; God loved his people because they were his people, Wheelwright noted, not because of anything they might do in his name. This sermon was completely in keeping with the Puritan view of grace and works, but Wheelwright's overt attack on the covenant of works, which the Boston ministers promoted, was considered seditious and dangerous.

Winthrop, Dudley, and the other magistrates censured Wheelwright while Vane, Hutchinson, and others supported him and signed a petition calling for his reinstatement. Winthrop and the others rejected the petition and moved to charge Wheelwright with sedition for challenging the authority of the works-based magistrates and ministers of the church. Vane opposed Winthrop's efforts to eject Wheelwright, but Winthrop's faction pushed for an election of the governor before Wheelwright's trial and Vane was voted out of office; Winthrop took his place. Vane then left the colony to return to England and Wheelwright was banished in the fall of 1637 CE. The last dissenter in the colony was now Anne Hutchinson who then became the central figure of the Antinomian Controversy.

Antinomian Controversy

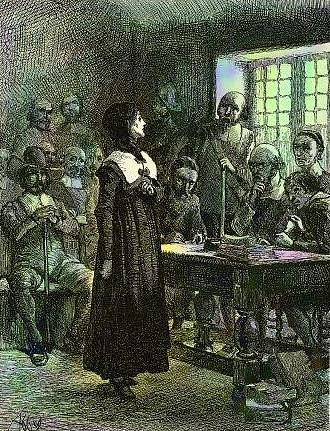

Hutchinson was called to answer the charges against her in November 1637 CE. She was charged with three offenses:

- As a woman exercising authority over men.

- As a denier of the significance and worth of a person's deeds.

- As a heretic who claimed the ability to identify who was 'saved' and who was not.

At the civil trial, John Cotton (who would eventually side with the Boston magistrates) tried to defend and apologize for Hutchinson, but his arguments were more or less ignored. As noted, Cotton was originally a champion of the covenant of grace and influenced both Hutchinson and Wheelwright. He seems to have later tempered his views after recognizing that he had contributed to a challenge of civil and religious authority in the colony by inspiring others who took his arguments to their natural conclusions.

Puritan theology, citing both the Bible and the works of the reformer John Calvin (l. 1509-1564 CE), claimed that Jesus Christ had not died on the cross to redeem all of humanity but only the elect, those God had chosen before they were even born, and that the gift of eternal life was God's gift, freely given. There was nothing, therefore, that anyone could do to earn this gift nor was it possible for those not of the elect to win election; the decision had already been made. One's good deeds, therefore, counted for nothing toward salvation. This was the covenant of grace, which Hutchinson argued for at her trial and which Cotton tried to help her defend.

John Winthrop and the other magistrates, all of whom acknowledged the primacy of the covenant of grace, argued that works did count because they were the outward, physical manifestation of one's inward spiritual state. Believers, Winthrop argued, should go to church, give alms, and practice Christian charity and good deeds as evidence of their election to salvation. Further, a covenant of works encouraged social order, harmony and, especially, unity in that everyone shared and participated in a single vision of Christian practice. Winthrop was not contesting the primacy of the covenant of grace; he was arguing against the rejection of a covenant of works.

This is the heart of the Antinomian Controversy. The dissenters were arguing “against the law” – against legalistic interpretations of scripture – while advocating for the freedom of the Holy Spirit to lead a believer in the path God had ordained. Their opponents were not denying the power of the Holy Spirit but claimed, citing the Bible, that "by their fruits shall ye know them" (Matthew 7:16) and that one's works identified one as a member of the elect though they could not justify one in God's eyes.

Hutchinson's Trial

Hutchinson was the daughter of a Puritan minister who had served in positions in the Anglican Church, been jailed for criticizing church policies, and had brought her and her siblings up reading them transcripts of his ecclesiastical trial and conviction. She was not only well-versed in the Bible but also in court proceedings and, further, had been encouraged by her father to always speak her mind, especially concerning her religious convictions.

Winthrop presided over the court and examined Hutchinson by questioning her on her beliefs and practices relating to the charges against her. Scholar David D. Hall describes Hutchinson's response:

She deflected the charges against her and embarrassed the ministers by questioning their account of the conversations held the previous December, a discussion she regarded as having been "private". Then, however, she described a spiritual quest triggered by the doubts she had begun to have about the legitimacy of Puritan clergy who remained in the Church of England. Was it possible that they were agents of the Antichrist? Wandering in a wilderness of "atheism", she found assurance of truth only after she heard a "voice" she interpreted as God speaking to her. (212)

This last claim of hers was too much for the magistrates to tolerate since she was claiming for herself knowledge only God could have and, therefore, was completely undermining the authority of the magistrates. This voice, Hutchinson claimed, was a gift from God and it told her who was among the elect and who was not. Cotton and Wheelwright, she claimed, were ministers in good standing with God and clearly among the elect; those ministers who downplayed the importance of grace and emphasized works were clearly not. In essence, those who agreed with Hutchinson's theology were saved; those who did not were not only outside of God's grace but leading others astray. Hutchinson was found guilty on all charges and placed under house arrest. In the spring of 1638 CE, she was banished after an ecclesiastical trial at which Cotton abandoned her and sided completely with the magistrates.

Conclusion

When Roger Williams had left the colony, he first found refuge among the Native Americans of the Wampanoag Confederacy before purchasing land from them and the Narragansett tribe to establish Providence Colony (modern-day Providence, Rhode Island). After Hutchinson was banished, Williams invited her to Providence, but she and her followers founded the colony of Portsmouth instead. Wheelwright would go on to establish another colony in New Hampshire at Exeter, and other dissenters would establish still other settlements elsewhere in New England.

In 1644 CE, while in England to secure a charter for his colony, Williams wrote his famous The Bloody Tenent of Persecution in which he defended the liberty of conscience and condemned religious persecution by civil authorities, arguing for a strict separation of church and state. The work was begun as a rebuttal of the Boston magistrates' claims and actions regarding himself, Wheelwright, and Hutchinson but focused on attacking the claims of a document he thought had been written by Cotton called A Model of Church and Civil Power, which supported the concept of civil authority prosecuting citizens for religious infractions.

Cotton, though he had nothing to do with that document, did agree with its views and so wrote a rebuttal to Williams' work, The Bloody Tenent Washed and Made White in the Blood of the Lamb in 1647 CE, justifying his views and those of the other works-based magistrates. This book then inspired another by Williams, The Bloody Tenent Yet More Bloody by Mr. Cotton's Endeavor to Wash it White in the Blood of the Lamb in 1652 CE. Their conflict was never resolved, and their works only went to strengthen the beliefs of people on either side of the argument who already had made their decision on the matter and were unlikely to be moved.

Those who wanted greater religious freedom went to Providence or Portsmouth or, later, Newport and like-minded colonies, while those who agreed with Winthrop's legalism remained in Massachusetts Bay Colony or went to Plymouth. In time, the differences in the various Puritan colonies diluted their vision while also causing conflicts which lost Puritanism the devotion of many of its members. The rise of other Christian sects, such as the Quakers and Baptists, also drew people away from Puritan congregations. Those who left were, to greater or lesser degrees, making the same arguments as the dissenters of the Antinomian Controversy and their demands for religious freedom would eventually inform the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights, establishing the separation of church and state in the new nation.