Aqueducts transport water from one place to another, achieving a regular and controlled supply to a place that would not otherwise receive sufficient quantities. Consequently, aqueducts met basic needs from antiquity onwards such as the irrigation of food crops and drinking fountains. Ancient aqueducts took the form of tunnels, surface channels and canals, covered clay pipes and monumental bridges.

Ever since the human race has lived in communities and farmed the land, water management has been a key factor in the well-being and prosperity of a community. Settlements not immediately near a freshwater source dug shafts into underground water tables to create wells and cisterns were also created to collect rainwater so that it could be used at a later date. Underground aqueducts and those built as bridges on the surface, however, allowed communities not only to access clean and fresh water but to live further from a water source and to utilise land which would otherwise have been unusable for agriculture.

Where Were the Earliest Aqueducts?

The earliest and simplest aqueducts were constructed of lengths of inverted clay tiles and sometimes pipes which channelled water over a short distance and followed the contours of the land. The earliest examples of these date from the Minoan civilization on Crete in the early 2nd millennium BCE and from contemporary Mesopotamia. Aqueducts were also an important feature of Mycenaean settlements in the 14th century BCE, ensuring autonomy against siege for the acropolis of Mycenae and the fortifications at Tiryns.

Aqueducts in Mesopotamia

The first sophisticated long-distance canal systems for water supply were constructed in the Assyrian Empire in the 9th century BCE and incorporated tunnels several kilometres in length. These engineering feats permitted the aqueducts to be constructed in a more direct line between source and outlet. The Babylonians in the 8th century BCE also built extensive and sophisticated canal systems. In the 7th century BCE, a wide canal crossed a 280 m long bridge to bring water to Nineveh, and water was brought through a 537-metre tunnel to supply Jerusalem.

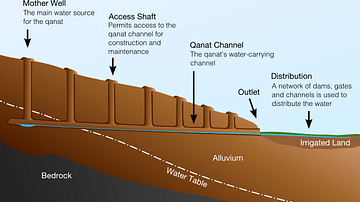

Another important innovation in water management was qanats. These probably originated from Persia (or perhaps Arabia) and were large underground galleries which collected groundwater. Tunnels at a lower level than the reservoir and often several kilometres in length then channelled off the water via the force of gravity. Such underground aqueducts as the Qanats were present throughout the ancient world from Egypt to China.

Greek Water Management

The first Greek large-scale water management projects occurred in the 7th century BCE and were usually to supply communal drinking fountains. Both Samos and Athens were supplied by long-distance aqueducts from the 6th century BCE; the former was 2.5 km long and included the famous 1 km tunnel designed by Eupalinus of Megara. Pisistratus constructed an aqueduct of 15 to 25 cm wide ceramic pipes in the Ilissus valley, 8 km long.

In the 4th century BCE, Priene in Asia Minor had a similar system of underground pipes which followed an artificial ditch covered in stone slabs. 3rd-century BCE Syracuse benefitted from no fewer than three aqueducts and Hellenistic Pergamon, c. 200 BCE, had some of the most sophisticated water management structures known at that time.

Roman Aqueducts

It is, however, the Romans who have rightly gained celebrity as the aqueduct builders par excellence. Hugely ambitious Roman engineering projects successfully mastered all kinds of difficult and dangerous terrain and made their magnificent arched aqueducts a common sight throughout the Roman Empire, supplying towns with water to meet not only basic needs but also those of large public Roman baths, decorative fountains (nymphaea) and private villas. Whilst most aqueducts continued to run along the surface and follow land contours wherever possible, the invention of the arch allowed for the construction of large-span structures, employing new materials such as concrete and waterproof cement, which could ignore unfavourable land features and draw the water along the straightest possible route along a regular gradient. Similarly, an increase in engineering expertise allowed for large-scale and deep tunnelling projects.

Another innovation which allowed for aqueducts to cross valleys was the large-scale inverted siphon. These were made of clay or multiple lead pipes reinforced with stone blocks and with the force of gravity and pressure as the water ran down the valley the momentum gained could drive the water up the opposite side. Arched bridges running across the valley floor could lessen the height the water had to fall and more importantly, go up on its ascent. Stopcocks to manage pressure and regulate the water flow, storage reservoirs, settling tanks to extract sediment and mesh filters at outlets were other features of Roman aqueducts. Sometimes water was also 'freshened' by aerating it through a system of small cascades. Interestingly, Roman aqueducts were also protected by law and no agricultural activity was allowed near them in case of damage by ploughing and root growth. On the other hand, agriculture did benefit from aqueducts, as in many cases, run-off channels were created to provide water for land irrigation.

The first aqueducts to serve Rome were the 16 km long Aqua Appia (312 BCE), the Anio Vetus (272-269 BCE) and the 91 km long Aqua Marcia (144-140 BCE). Steadily, the network increased and even created connections between aqueducts: the Aqua Tepula (126-125 BCE), Julia (33 BCE), Virgo (22-19 BCE), Alsietina (2 BCE), Aqua Claudia and Anio Novus (completed in 52 CE), Aqua Traiana (109 CE) and the Aqua Alexandrina (226 CE). Gradually, other aqueducts were built across Italy, for example, in Alatri (130-120 BCE) and Pompeii (c. 80 BCE). Julius Caesar built an aqueduct at Antioch, the first outside Italy. Augustus (r. 27 BCE - 14 CE)oversaw the construction of aqueducts at Carthage, Ephesus, and the 96 km aqueduct which served Naples. Indeed, the 1st century CE saw an explosion of aqueduct construction, perhaps connected to the spread of Roman culture and their love of bathing and fountains but also to meet the water needs of ever-larger population concentrations.

From the 1st to the 2nd centuries CE, the very limits of architectural feasibility were stretched and some of the largest Roman aqueducts were constructed. These had two or three arcades of arches and reached prodigious heights. The aqueduct of Segovia was 28 m high and the Pont du Gard in southern France was 49 m in height, both of which still survive today as spectacular monuments to the skill and audacity of Roman engineers.