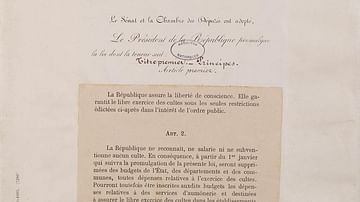

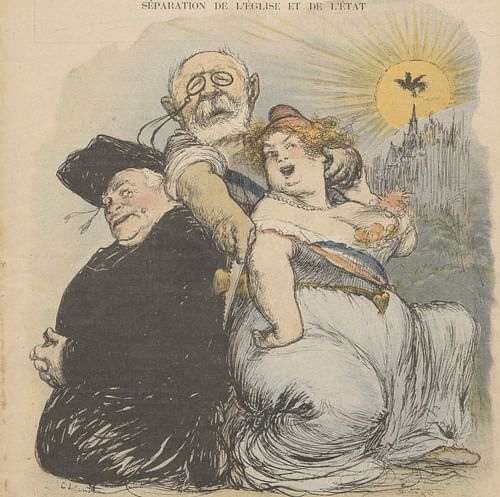

The Law of Associations was adopted by the French Parliament on 3 July 1901 to limit the influence of Catholic teaching orders as the first step toward the formal separation of church and state that would follow in 1905. Of 16,904 religious teaching institutions, almost 14,000 were closed.

Religion after the French Revolution

A religious crisis occupied France for ten years before Napoleon Bonaparte (l. 1769-1821) came to power to reverse many of the gains of the French Revolution (1789-1799). By all accounts, Napoleon was a man without strong religious leanings. He recognized, however, that the majority of French people were Roman Catholic and sought to bring the Church under his control for political purposes. An alliance with the Church became a political necessity. The Concordat was signed in 1801 between Napoleon and Pope Pius VII (l. 1742-1823) and "was to rule the relations between France and the papacy for more than a century" (Walker, 669).

After the signing of the Concordat, there were periods when the Church appeared to retrieve its influential place in French society. There were also diplomatic crises, intrigues, and considerable controversies which took place in the last two decades of the 19th century concerning the relations between church and state. Conflicts between the Vatican and the French government hardened opposition toward the Church and played into the hands of anticlerical forces who sought the termination of the Concordat of 1801. The Law of Associations in 1901 prepared the way for the eventual Law of Separation of Church and State that would end the Concordat in 1905. Of the many individuals who played a part in this drama, several stand out for special mention.

René Waldeck-Rousseau

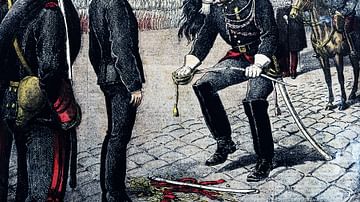

In 1899, René Waldeck-Rousseau (l. 1846-1904) was called upon to lead the French government as President of the Council in the wake of political chaos brought about by the Dreyfus Affair. Waldeck-Rousseau's government lasted three years, during which time he also held the position of Minister of the Interior and Religions. Seeing the 1801 Napoleonic Concordat as a means to control the clergy, he supported proposals for the separation of church and state. On 28 October 1900, he gave a speech at Toulouse where he outlined a project for the Law of Associations that would require religious teaching orders to request authorization to remain open. This proposed law concerned cultural associations and would enforce restraints on religious teaching orders.

In his speech, Waldeck-Rousseau described himself as a man without a sectarian spirit. He referenced the Concordat of 1801, which governed the relations between church and state. His main concern and the object of the proposed law was the religious teaching orders of the Catholic Church. These orders had grown in number and militancy and, in his opinion, risked dividing France into two groups by providing religious instruction in their schools. One group would become more democratic, while the other group would remain under the influence of religious dogma that had survived the revolutionary and intellectual movements of the 18th century.

Waldeck-Rousseau saw the rising influence of the Catholic Church as a powerful rival to the state, an influence that produced an intolerable situation against which all administrative measures had been ineffective. He viewed the proposed Law of Associations as the solution to educational concerns in requiring authorization of teaching orders by the government. He concluded his historic speech by announcing that the Law of Associations would be the departure point of the greatest and freest social evolution and, in addition, the indispensable guarantee of the most necessary rights of modern society. Religious orders could no longer organize or remain in existence without state authorization, and teachers belonging to these teaching orders were not permitted to lead educational institutions.

Émile Combes

In June 1902, Émile Combes (l. 1835-1921) replaced Waldeck-Rousseau as President of the Council. Neither President Émile Loubet nor his secretary general Abel Combarieu (l. 1856=1944) expressed enthusiasm for Combes. In excerpts from his Souvenirs, published to reflect on the political atmosphere of these crucial years of the Third Republic, Combarieu wrote that among the essential policies of Combes's cabinet was the firm application of the recent Law of Associations and upholding of the Concordat.

Combes found in the writings of the famous poet and novelist Anatole France (l. 1844-1924) a defense of his strict application of the Law of Associations. Anatole France, in the preface to Combes's book, Une compagne laïque, evoked the Dreyfus Affair and the antisemitism supposedly orchestrated by the Catholic Church. He described the agitation that the 1901 law provoked, the surprise and indignation among the clericals at the closure of unauthorized teaching institutions, the organized resistance to the law in Brittany, and the Church's exhortations that led to violence. Parliamentarians claimed that the Catholic Church had constantly violated the Concordat and had pushed the Republican party to its limits, and when the Republican party turned against the Church and requested accountability for the Church's actions, the Church only requested one thing – the upholding of the Concordat.

Combes's policies did not go uncontested. Combarieu serves as an eyewitness to the intrigue and the tensions in the summer of 1902 produced by the application of the law of 1901 and the shutting down of religious establishments. The news that nuns were expelled from unauthorized convents was reported to have grieved President Émile Loubet and his wife, who deplored the task undertaken by Combes as damaging for her husband and harmful for France. The policies of Combes, however, appeared to have the support of a majority in Parliament, and the president found himself powerless to intervene. Waldeck-Rousseau remarked to the president that Combes was carrying out a thoughtless policy that was contrary to what had been understood at the time the law of 1901 was adopted. He reaffirmed that the object of the law had been to prevent further multiplication of religious teaching establishments and did not concern existing establishments.

Further opposition to Combes came from the Jewish intellectual Bernard Lazare (l. 1865-1903). In a letter dated 6 August 1902, Lazare expressed his opposition to Combes and the laws enacted in the pretense of educational liberty. He challenged the partisan exploitation of the Dreyfus Affair to tear down the religious teaching orders and the Church. Lazare made it clear that he was not defending the Church against which he had waged combat in the past. Yet he refused to accept either the dogmas formulated by the state or the dogmas of the church. He insisted on one thing – complete liberty for reason – which did not require force to triumph.

Although Émile Combes severely applied the 1901 Law of Associations, he continued to uphold the Concordat even if the door was left open for its later rescindment. His early support to maintain the Concordat is evident during a debate in January 1903 on state funds allocated to support the concordataire churches under the terms of the Concordat. He believed that the suppression of these funds for churches would bring about confusion. Combes asserted that when he came to power he had promised to support the continuation of the provisions of the Concordat. He confessed that philosophically, and in his political sensibilities on the Left, he wished that free thought supported by reason alone might lead people throughout life, but realized that moment had not yet arrived. Until that time, he needed to postpone the Left's desire for separation of church and state and the repeal of the Concordat.

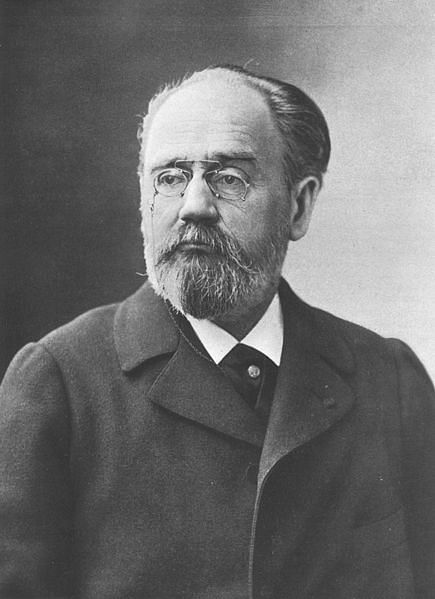

Émile Zola

Émile Zola's (l. 1840-1902) final novel Vérité was published posthumously in 1903 in which he recalled the conflict of the Dreyfus Affair and the struggle against religious schools. He asserted that Rome was the cause of the nation's suffering and its division into two Frances at war with each other. Zola described France as the last of the great Catholic powers who alone had the men, money, and power to impose Catholicism in the world. He contended that Rome chose France as the arena of struggle in its desire to reconquer temporal power and permit it to achieve its secular dream of universal domination. Zola also claimed that under the politics of Pope Leo XIII (l. 1810-1902), the Republic was accepted in order to be invaded by the Catholic Church. He ascribed fault to the Jesuits and other teaching orders that in 30 years tripled the number of students and expanded their influence throughout the country.

Louis Méjan

There were some who believed the Law of Associations prefigured an inevitable separation of church and state. Louis Méjan (l. 1874-1955), son of a Calvinist pastor, was one of the first to see separation on the horizon. He recounted conversations with politicians to whom he expressed his concern that the Law of Associations would lead to the separation of church and state. In a conversation with Henri Brisson (l. 1835-1912) in 1902, one of the founders of the Third Republic, Brisson told Méjan: "Before we might achieve the separation of Church and State, France must live through forty years of happiness" (Bruley, 82). On another occasion, in conversation with Charles Dumay, Director of Religious Affairs, a post later occupied by Méjan, Dumay opined that the separation of church and state would be a madness similar to that of a government opening the cages of ferocious beasts in a public place to devour the crowd. Whether the separation was madness or not, France never achieved 40 years of happiness, and separation soon become a reality.

Alphonse Aulard

The historian Alphonse Aulard (l. 1849-1928), a recognized expert on the French Revolution, expressed his support for a necessary separation in articles published in La Dépêche de Toulouse in April 1903. Aulard addressed those on both sides of the issue – those who advocated separation and those who supported the maintenance of the Concordat of 1801. In a humorous manner, he named the two groups respectively Tant-Mieux and Tant-Pis (So Much the Better and Too Bad) to explain the arguments for and against separation. Tant-Pis accused Combes of seeking reprisals against the pope stemming from a quarrel on the interpretation of the Concordat in the nomination of bishops. Tant-Pis supported the Concordat in order to have the means to control the Catholic Church with financial support. Tant-Pis also feared that a free church in a free state would soon lead to the Church as a mistress and the state as a slave. Tant-Mieux did not understand how the Church would be freer if the clergy no longer received their salaries from the state and claimed that without state support the Church would no longer have the means to wage war against modern civilization. Tant-Mieux had no fear of the loss of diplomatic relations since the pope advised the clergy to make France a Catholic Republic. Tant-Pis concluded that it would be easier to maintain the Concordat. Tant-Mieux responded that the Concordat was outdated and that the regime needed to be changed in conformity with the principles of the present-day French Republic.

During a speech at the Vatican to counter the aggressive stance of Combes's government, Pope Pius X (l. 1835-1914) inserted himself into the debate in November 1903. He declared it his duty to intervene in matters of power, justice, and equity. This duty extended both to private and public life, to social and political issues, and not only to those who obey but also to those who command. As supreme head of the Church, the pope desired to maintain good relations with princes and governors. Yet he clearly declared that it was necessary that the Church attend to politics and that no one could separate political matters from faith and morals.

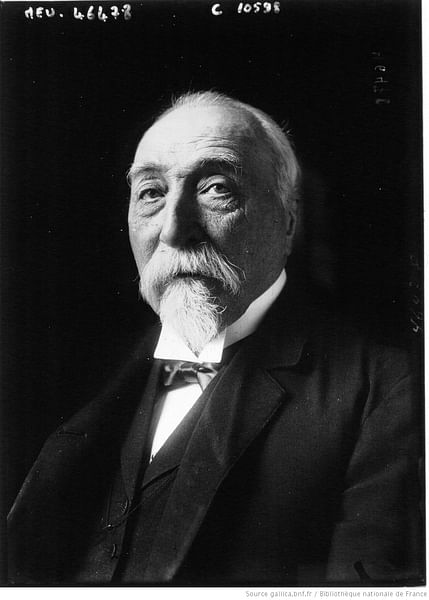

Georges Clemenceau

Later that same month, statesman Georges Clemenceau (l. 1841-1929) denounced the tyranny of both a secular state and the Catholic Church. The context was debate over whether to repeal the Law Falloux of 1850 enacted during the Second Republic. This law benefited the Catholic Church in granting greater liberty in primary and secondary school education. Clemenceau called Catholics citizens of a Roman society stuck into revolutionary French society and members of an international corporation in submission to a foreign sovereign. He also recognized the dangers of a secular state and feared the totalitarian tendencies of socialism. In his speech, the state was described in these words:

The State, I know well. It has a long history of murder and blood. All the crimes which have taken place in the world—the massacres, the wars, the stakes, the tortures—all have been justified in the interest of the State, for reasons of State. . . . Because I am the enemy of the king, of the emperor and of the pope, I am the enemy of the omnipotent State, the sovereign master of humanity.

(Clemenceau, 42)