Ardashir I (l. c. 180-241 CE, r. 224-240 CE) was the founder of the Persian Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE) and father of the great Sassanian king Shapur I (r. 240-270 CE). He is also known as Ardashir I Babakan, Ardeshir I, Ardashir the Unifier, and Ardashir Papakan.

He was the son of the prince of Istakhr, Papak (also given as Babak and Papag, r. c. 205-210 CE) and the Princess Rodak of the Shabankareh tribe (suggested by some scholars as Kurdish) and born in Tirdeh, Persis c. 180 CE. He is also believed to have been grandson of the High Priest of Zoroastrianism, Sasan (c. 3rd century CE), after whom the Sassanian Empire is named, though some evidence suggests he was Sasan's son and later adopted by Papak.

Ardashir I was a general in the Parthian army under the reign of the king Artabanus IV (r. 213-224 CE). His family controlled the symbolically significant region of Istakhr where the ruins of the Achaemenid capital of Persepolis lay. Even though the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) was a distant memory, it still resonated powerfully throughout the region at the time of Ardashir I, and his family refused to relinquish control of it to Artabanus IV. Further complicating relations between the two, Ardashir I had made significant gains for himself in the region at the expense of Artabanus IV whose power was waning.

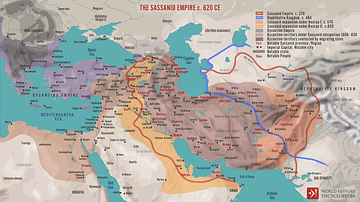

In 224 CE, Ardashir I defeated Artabanus IV in battle, toppling the Parthian Empire (247 BCE - 224 CE) and founding his own which he modeled on the success of the earlier Persian Achaemenid Empire. He soon after concentrated his efforts on urban development and military campaigns against Rome which were universally successful. He co-ruled with his son Shapur I toward the end of his reign and died peacefully after assuring that the empire he had founded would continue in good hands. He is considered one of the greatest kings of the Near East generally and of the Sassanian Empire specifically.

Failing Parthian Empire

After the fall of the Achaemenid Empire to Alexander the Great in 330 BCE, the Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE) held the region until they were replaced by the Parthians. The Parthian king Arsaces I (r. 247-217 BCE) established an independent kingdom of Parthia while the Seleucids were still firmly in control but, as their power waned, Parthia took advantage and enlarged their territories, finally controlling the majority of what had once been the Achaemenid Empire.

Recognizing the weakness of a centralized government – and especially of a centralized military deployed from a set point (as in the case of both the Achaemenids and Seleucids) – the Parthians decentralized both to enable more efficient administration and defense. Parthians satraps had a greater degree of autonomy and could field armies for defense without having to consult with the king first.

This model worked well for the Parthians for most of the empire's history but, by the time Ardashir I was born, their vitality was being steadily drained through engagements with the Roman Empire and internal dissent. The decentralization which had worked so well earlier was now a liability because Rome could field more men which small armies from individual satrapies could not contend with. Further, the autonomy of the satraps by this time resulted in mini kingdoms within the empire which were more concerned with their own self-interest than the preservation of the empire.

Early Life & Rise to Power

The satrap of Ardashir's region of Persis was Guchehr (also given as Gochihr) with whom Ardashir's father, Papak, had some disagreement. Sources are unclear on whether Papak – a high priest of Zoroastrianism and keeper of a Fire Temple as well as a royal – initiated a rebellion or was simply one of the leaders of a movement already in motion. Papak's eldest son, Shapur, seems to have been groomed to take over his father's position while his second son, Ardashir, was sent at age seven to the commander of Fort Darabgerd for instruction in military matters and administration.

Nothing is known of Ardashir's time at Darabgerd but he succeeded the commander at the fort sometime before 200 CE and so must have been considered an able soldier and administrator by this time. In 200 CE, Papak overthrew Guchehr and took the throne, which he then passed on to his son Shapur before his death. Ardashir had taken part in the coup with his family and seems to have contributed more than Shapur so he naturally took offense at being passed over in favor of his brother. He challenged Shapur's authority, and the two prepared for battle, but Shapur was killed by falling stones from a ruined battlement before their forces could meet.

Ardashir then declared himself king of Persis in 208 CE which was met by objections from his younger brothers so, rather than plunge the region into civil war, Ardashir had them all executed before they could mount any armed resistance. This move did not prevent other nobles from following the same course as the brothers and so Ardashir mounted campaigns and defeated all of them. These moves brought him to the attention of the Parthian King of Kings Artabanus IV, but Ardashir seems to have been confident in his abilities having been well trained at Darabgerd and already with a number of military victories to his credit.

Scholar Kaveh Farrokh suggests that Ardashir's confidence, and later success, was due to his personal charisma and his family's link with the highland Kurds:

Ardashir's success in receiving the support of the Medes and Kurds in his revolt against the Parthians may have been partly due to his own possible heritage as a highlander. (178)

Ardashir's challenge to the king's authority could not go unanswered but Artabanus IV did not command the kinds of resources his predecessors had. Roman incursions into the Parthian empire had been ongoing since 116 CE, and by 198 CE, the empire was the weakest it had ever been. There were many satraps throughout the region – long before Papak launched his coup – who were dissatisfied with how Artabanus IV was handling the various threats and these were now courted by Ardashir and brought into his rebellion. In 224 CE, at the Battle of Hormozdgan, Ardashir defeated Artabanus IV and the Parthian Empire fell. Pockets of resistance remained afterwards and some kingdoms retained their Parthian identity but, formally, Hormozdgan was the end of the empire.

Early Reign & War with Rome

Ardashir's first order of business was to unite the disparate regions of the empire and crush any resistance; both of which he accomplished between 224-227 CE. During this same time, he commissioned a number of building projects, including the restoration of the city of Ctesiphon, formerly the capital of the Parthian Empire, which had been destroyed by Septimus Severus in 197 CE. He afterwards made Ctesiphon the Sassanian capital.

He centralized the government and the military, bringing the army back into line in accordance with the earlier Achaemenid model, and retained the best aspects of both Seleucid and Parthian warfare regarding body armor and, in the case of the Parthians, the use of cavalry in battle. He revived the Achaemenid model of a standing army (the spada or spah) and a levy (the kara) imposed on satraps to fill the ranks and improved upon the Parthian cavalry in the form of the elite mounted cataphracts known as the Savarans, heavily armored, fully equipped, and highly trained warriors who were also expert horsemen.

In 226-227 CE Ardashir I tried, unsuccessfully, to take the city of Hatra which remained an independent Parthian kingdom. Most scholars accept Ardashir I's coronation at Ctesiphon as occurring in 224 CE but there is some evidence to suggest he was not coronated until after he had united the majority of the lands, and rebuilt the city, in either 226 or 227 CE once he had abandoned attempts at integrating Hatra into his empire. There are valid reasons for accepting these later dates as they are suggested by Roman historians in relating the accounts of the Sassanian wars with Rome and he most likely would not have been able to rebuild Ctesiphon prior to 226 CE.

The Romans had grown used to dealing with the failing Parthian Empire and so were ill-prepared for the advent of a new Persian empire which was strong enough to make demands. Farrokh writes:

The Romans soon realized that the “new management” in Persia was a power to be reckoned with. Ardashir boldly claimed “his rightful inheritance from his forefathers” in having all the territories of the ancient Achaemenid Empire as far as the Aegean Sea restituted to Persia. The Romans who occupied all territories west of the Tigris knew that a showdown with the new Sassanian Empire was all but inevitable. (184)

Before this “showdown” could begin in earnest, Ardashir I and his son Shapur I marched their armies into Mesopotamia and Syria and drove the Romans out in 229 CE. The Roman emperor Alexander Severus (r. 222-235 CE) sent Ardashir I a letter demanding his withdrawal, but Ardashir I ignored him and, to add insult, took Cappadocia. Alexander Severus again wrote Ardashir I reprimanding him and Ardashir I sent 400 delegates in answer who repeated his demand that Rome vacate the regions once belonging to the Achaemenid Empire and return them to him, their rightful king. Severus responded by arresting the delegates, stripping them of their weapons and clothing, and sentencing them to work as slaves on Roman farms. He then mounted a campaign to deal with the new Persian king for good.

Severus' Campaign

In 231 CE, Alexander Severus launched his war along three fronts. The first Roman army marched through Armenia to come at Ardashir from the north, the second came up through Mesopotamia from the south, and the third came toward the Sassanian capital of Ctesiphon from between these two. The northern advance took back Cappadocia and ravaged Armenia while the southern made steady progress upwards and the center was also successful, but none of the commanders were aware that, so far, they had been facing only a portion of the Sassanian army and had yet to encounter the heavily-armed and highly-trained cavalry, including the Savaran knights.

The momentum of the Roman troops was stopped in 233 CE when Severus' armies met the Sassanian cavalry at the Battle of Ctesiphon and were defeated. The Savarans were masters of the lance and drove the Roman infantry into smaller formations where they were easily killed by mounted Sassanian archers pouring arrows down upon them repeatedly and retreating quickly only to return and strike again.

Severus' strategy of the three-pronged attack was misguided in the end because, as Farrokh notes, all Ardashir had to do was to “observe the Roman axes of advance and then decide where he was going to strike with the bulk of his forces” (185). A single, large, Roman force, in the end, would have been far more effective against the fewer troops of the Sassanians. Severus returned to Rome where he announced a great victory while Ardashir I, tired from campaigning for so many years of his reign, allowed him to go and, further, passed the responsibility for further campaigns to his son Shapur I.

Building Projects & Policies

A number of modern-day scholars have suggested that Ardashir I – and the Sassanians in general – could have had no knowledge of the Achaemenid Empire because it had fallen some 500 years earlier and there is no extant written evidence that the Sassanians had any specific information on the first Persian empire. This claim ignores the fact that Persian culture held to an oral tradition and so, of course, there would be no written records. The Persians prided themselves on their skill in storytelling and the history of the Achaemenid Empire and its great kings would have been passed down from generation to generation by the storytellers.

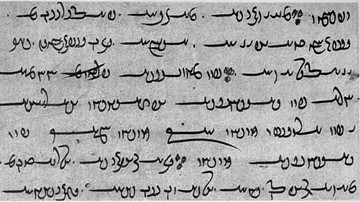

Ardashir I's knowledge of the past, stretching back to the Achaemenid Empire, is evidenced most clearly in his efforts to preserve the religious tradition of his people in writing. The religion of Zoroastrianism was an oral faith – there was absolutely no written scripture – and so the faith was kept by the priests who recited the precepts of the prophet Zoroaster in the ancient language of Avestan. Each generation of priests taught the memorized verses to the next until Ardashir I decreed that they should be committed to writing. He invited Zoroastrian priests to his court to recite the central text of the religion – the Avesta – and have it transcribed. In order to accomplish this, an entirely new script had to be developed from existing Aramaic in order to preserve the inflection and precise pronunciation of the Avestan spoken language.

This effort was begun under Ardashir I, continued by Shapur I, but only completed under Shapur II (r. 309-379 CE) and Kosrau I (r. 531-579 CE). Ardashir I's vision of preserving the past saved the Avesta from being lost to time, especially when one considers the suppression of Zoroastrianism after the Muslim-Arab invasions of the 7th century CE when so many Zoroastrian texts were destroyed in an effort to establish the supremacy of Islam. If the faith had remained an oral tradition, the massacre of the Zoroastrian priests would have silenced it forever but, as it was, the Avesta was preserved in writing and is still an integral part of the living religion of Zoroastrianism in the present day.

It seems abundantly clear from the primary sources that Ardashir I knew the history of his people well and made the most of it by keeping what worked best for his own empire and discarding other aspects which had proven themselves ineffective. One of the most impressive facets of the Sassanian Empire has always been its vision in retaining the best of the past, improving upon it, and discarding other elements.

Along these lines, Ardashir I commissioned building projects which mirrored the grandeur of Achaemenid masterpieces like Persepolis but made use of Parthian innovations like the arch. Parthian architecture emphasized circularity – symbolizing wholeness, stability – and Ardashir I's works continued this tradition. He also borrowed from Roman architecture the concept of the dome from Roman architecture but, instead of a dome set upon the top of a structure, it grew organically from the ground up, often supported by the arch. Precisely which extant ruins were commissioned by Ardashir I is difficult to discern but it is believed that his son continued his vision and, possibly, the great standing arch of Taq Kasra at Ctesiphon was constructed under Shapur I along the lines of the vision of his father.

One of the best-known architectural innovations of Ardashir I's reign was the development of the minaret, which took the concept of the dome to a higher level. Instead of a simple dome topping a structure, the minaret accentuated height by its spire and added to the grandeur of a structure through ornamentation. The minarets of the Near East, which today are almost synonymous with Muslim-Arabian architecture, were actually Persian in origin and date to the time of Ardashir I's reign.

Ardashir I's father and, possibly, grandfather had both been Zoroastrian high priests in charge of maintaining the Fire Temples dedicated to the god Ahura Mazda. Ardashir I, therefore, not surprisingly, made Zoroastrianism the state religion but, in keeping with the Achaemenid policy of religious tolerance, allowed other faiths to worship as they saw fit. It appears that Ardashir I was not as tolerant as perhaps the Achaemenid kings such as Cyrus the Great or Darius I were as there is some evidence that non-Zoroastrians were accorded less rights than those of Ardashir I's faith, but this trend would be reversed under Shapur I.

Conclusion

Ardashir I had co-ruled with his son toward the end of his reign and finally surrendered responsibility fully in 240 CE. Shapur I now reigned as King of Kings of the Sassanian Empire, though Ardashir I is thought to have continued to advise on matters of state until his death in 241 CE. Ardashir I had united the region under his reign and established an empire which would last for over 400 years. Farrokh writes:

During his 20-year reign, Ardashir not only consolidated Sassanian power, but was able to defeat Roman attempts at destroying the new Iranian Empire. (184)

His vision was continued by Shapur I who, in keeping with the Persian talent for adaptation and improvement, discarded his father's tendency toward religious intolerance and fully embraced the Achaemenid model of Cyrus the Great. Under Shapur I, all faiths were welcome to worship freely. Shapur I, like his father, is also regarded as among the greatest of the Sassanian kings but his reign was informed by the first king and founder of the empire whose impressive talents included the ability to see what needed to be done and the skill and courage to make that vision a reality.