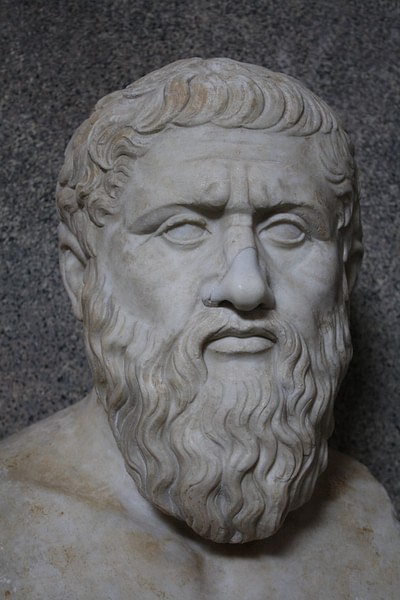

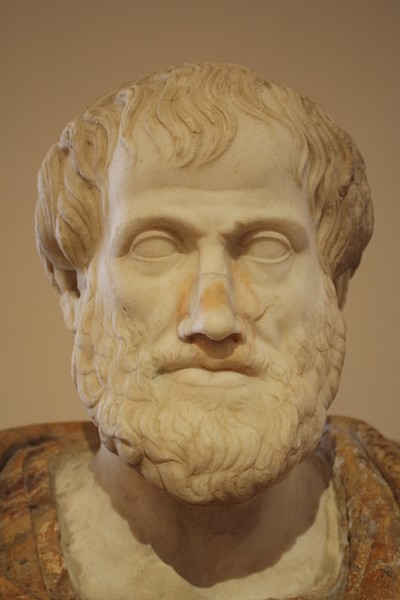

Aristotle of Stagira (l. 384-322 BCE) was a Greek philosopher who pioneered systematic, scientific examination in literally every area of human knowledge and was known, in his time, as "the man who knew everything" and later simply as "The Philosopher”, needing no further qualification as his fame was so widespread.

He literally invented the concept of metaphysics single-handedly when he (or one of his scribes) placed his book on abstract philosophical speculation after his book on physics (metaphysics literally means “after physics”) and standardized in learning – how information is collected, assimilated and interpreted, and then communicated – across numerous disciplines.

During the later Middle Ages (c. 1300-1500 CE), he was referred to as "The Master", most notably in Dante's Inferno where the author did not need to even identify Aristotle by name for him to be recognized. This particular epithet is apt in that Aristotle wrote on, and was considered a master in, disciplines as diverse as biology, politics, metaphysics, agriculture, literature, botany, medicine, mathematics, physics, ethics, logic, and the theatre. He is traditionally linked in sequence with Socrates and Plato in the triad of the three greatest Greek philosophers.

Plato (l. c. 424/423-348/347 BCE) was a student of Socrates (l. c. 469/470-399 BCE) and Aristotle studied under Plato. The student and teacher disagreed on a fundamental aspect of Plato's philosophy – the insistence on a higher realm of Forms which made objective reality possible on the earthly plane – although, contrary to the claims of some scholars this did not cause any rift between them. Aristotle would build upon Plato's theories to advance his own original thought and, although he rejected Plato's Theory of Forms, he never disparaged his former master's basic philosophy.

He was hired by Philip II, King of Macedon (r. 359-336 BCE) as tutor for his son Alexander the Great (l. 356-323 BCE) and made such an impression on the youth that Alexander carried Aristotle's works with him on campaign and introduced Aristotelian philosophy to the east when he conquered the Persian Empire. Through Alexander, Aristotle's works were spread throughout the known world of the time, influencing ancient philosophy and providing a foundation for the development of Jewish, Christian, and Muslim theology.

Early Life

Aristotle was born in 384 BCE in Stagira, Greece, on the border of Macedonia. His father, Nichomachus, was the court physician to the Macedonian king and died when Aristotle was ten years old. His uncle assumed guardianship of the boy and saw to his education. Aristotle probably spent time with the tutors at the Macedonian court, as the son and nephew of palace staff, but this not known with certainty. When he was 18, Aristotle was sent to Athens to study at Plato's Academy where he remained for the next 20 years.

He was an exceptional student, graduated early, and was awarded a position on the faculty teaching rhetoric and dialogue. It appears that Aristotle thought he would take over the Academy after Plato's death and, when that position was given to Plato's nephew Speusippus, Aristotle left Athens to conduct experiments and study on his own in the islands of the Greek Archipelago.

Aristotle & Alexander the Great

In 343 BCE Aristotle was summoned by King Philip II of Macedon to tutor his son Alexander and held this post for the next seven years, until Alexander ascended to the throne in 336 BCE and began his famous conquests. By 335 BCE, Aristotle had returned to Athens but the two men remained in contact through letters, and Aristotle's influence on the conqueror can be seen in the latter's skillful and diplomatic handling of difficult political problems throughout his career. Alexander's habit of carrying books with him on campaign and his wide reading have been attributed to Aristotle's influence as has Alexander's appreciation for art and culture.

Aristotle, who held a low opinion of non-Greek “barbarians” generally and Persians specifically, encouraged Alexander's conquest of their empire. As with most – if not all - Greeks, Aristotle would have been brought up hearing stories of the Battle of Marathon of 490 BCE, the Persian Invasion of 480 BCE, and the Greek triumph over the Persian forces at Salamis and Plataea. His advocacy of conquest, then, is hardly surprising considering the cultural atmosphere he grew up in which had remained largely anti-Persian.

Even without this consideration, Aristotle was philosophically pro-war on the grounds that it provided opportunity for greatness and the application of one's personal excellence to practical, difficult, situations. Aristotle believed that the final purpose for human existence was happiness (eudaimonia – literally, “to be possessed of a good spirit”) and this happiness could be realized by maintaining a virtuous life which developed one's arete (“personal excellence”).

Beliefs & Differences with Plato

Once Aristotle returned to Athens in 335 BCE, he set up his own school, The Lyceum, a rival to Plato's Academy. Aristotle was a Teleologist, an individual who believes in `end causes' and final purposes in life, and believed that everything and everyone in the world had a purpose for existing and, further, these final purposes could be ascertained from observation of the known world.

Plato, who also dealt with first causes and final purposes, considered them more idealistically and believed they could be known through apprehension of a higher, invisible, plane of truth he called the `Realm of Forms'. Plato's philosophy was deeply rooted in the mysticism of the Pythagorean School, founded by the Pre-Socratic philosopher and mystic Pythagoras (l. c. 571-c.497 BCE). Pythagoras emphasized the immortality of the soul and the importance of virtuous living, recognizing there are essential, indisputable truths in life which one must recognize and adhere to in order to live a good life.

Plato was also significantly influenced by another Pre-Socratic philosopher, the sophist Protagoras (l. c. 485-415 BCE), considered the first relativist thinker. Protagoras famously maintained that “Of all things, a man is the measure”, meaning that individual perception determines truth. There can be no objective truth in any given situation, Protagoras argued, because all observable phenomenon or emotional or psychological experiences are subject to an individual's interpretation.

Aristotle could never accept Plato's Theory of Forms nor did he believe in positing the unseen as an explanation for the observable world when one could work from what one could see backwards toward a First Cause. In his Physics and Metaphysics, Aristotle claims the First Cause in the universe is the Prime Mover – that which moves all else but is itself unmoved. To Aristotle, this made more sense than the realm of Forms.

To Aristotle, a horse is beautiful because of certain characteristics humans associate with the concept of beauty: the horse's coat is a pleasing color, it is in good health, it has good form in the ring. To claim that a horse is beautiful because of some unseen and unproveable realm of Perfect Beauty was untenable to Aristotle because any claim should require proof in order to be accepted.

In rejecting the Theory of Forms, Aristotle mentions Plato and how he hates to argue against his former teacher, a man who remains dear to him. He feels he must address the impracticality of Plato's theory, however, and encourages Platonists to abandon it, writing:

In the interest of truth, one should perhaps think a man, especially if he is a philosopher, had better give up even theories that once were his own, and in fact must do so…it is our sacred duty to honor truth more highly than friends [i.e. Plato]. (Nicomachean Ethics I.1096a.15)

Plato claimed that intellectual concepts of the Truth could not be gained from experience and nothing could actually be learned. He most notably demonstrates this in his dialogue of the Meno where he argues that all learning is actually “remembering” from a past life. Aristotle rejected this claim, arguing that knowledge was obviously learned because people could be taught and this was evident in changes in their perception of life and behavior.

A good man was good, Aristotle argued, because he had been taught the value of living a good, virtuous life. If an individual could not actually “learn”, but only “remember” essential truths from a past life in which they were “good”, then that person could not be considered “good” themselves. The virtue a human exhibited in life was the result of that person deciding to behave a certain way and practicing virtuous habits for their own sake, not for reputation or praise from others. Aristotle writes:

Honor seems to depend on those who confer it rather than on him who receives it, whereas our guess is that the good is a man's own possession which cannot easily be taken away from him. (Nicomachean Ethics I.1095b.25)

Aristotle advocated moderation in all things in order to attain this “good” in life which, ultimately, was a happiness no person or set of circumstances could take or diminish. Aristotle maintained that “a man becomes just by performing just acts and self-controlled by performing acts of self-control” (Nicomachean Ethics I.1105b.10). This self-control was exemplified by his concept of the Golden Mean. Aristotle writes:

In regard to pleasures and pains…the mean is self-control and the excess is self-indulgence. In taking and giving money, the mean is generosity, the excess and deficiency are extravagance and stinginess. In these vices excess and deficiency work in opposite ways: an extravagant man exceeds in spending and is deficient in taking, while a stingy man exceeds in taking and is deficient in spending. (Nicomachean Ethics I.1107b.5-10)

The Golden Mean provides a control which acts to correct one's behavior. If one knows that one is prone to the excess of extravagance, one should revert to the extreme opposite of stinginess. Since one's natural inclination will be to spend freely, making a conscious attempt to spend nothing will result in one drifting to the moderate ground between the extremes.

The Golden Mean was among the many precepts Aristotle taught to his students at the Lyceum. His habit of walking back and forth as he taught earned the Lyceum the name of the Peripatetic School (from the Greek word for walking around, peripatetikos). Aristotle's favorite student at the school was Theophrastus who would succeed him as leader of the school and who collected and published his works. Some scholars have claimed, in fact, that what exists today of Aristotle's work was never written to be published but was only lecture notes for classes which Theophrastus and others admired a great deal and so had copied and distributed.

Famous Contributions & Works

The Golden Mean is one of Aristotle's best-known contributions to philosophical thought (after the Prime Mover) but it should be noted that this was only in the realm of ethics and Aristotle contributed to every branch of knowledge available in his time. In ethics, he also famously explored the difference between voluntary actions and involuntary actions, encouraging people to try to fill their lives with as many voluntary actions as possible in order to achieve the greatest happiness. He understood that there were many chores and responsibilities one would meet in a day which one would rather not do but suggested one consider these apparent annoyances as opportunities and avenues to happiness.

For example, one might not want to do the dishes and would consider having to perform this chore and involuntary action. Aristotle would suggest one look at cleaning the dishes as a means to the desirable end of having a clean kitchen and clean plates to use at the next meal. The same would apply to a job one does not like. Instead of seeing the job as an obstacle to happiness, one should look at it as the means by which one is able to buy groceries, clothes, take trips, and enjoy hobbies. The value of positive thinking and the importance of gratitude have been highlighted by a number of authors in different disciplines in the 20th and 21st centuries CE but Aristotle was a much earlier proponent of the same view.

In his work On the Soul, Aristotle addresses the issue of memory-as-fact, claiming that one's memories are impressions but not reliable records of what really happened. A memory assumes a different value as one undergoes new experiences and so one's memory of an unpleasant event (say a car accident) will change if, because of that car accident, one met the love of one's life. People pick and choose what they will remember, and how they will remember it, based on the emotional narrative they are telling themselves and others. This concept has been explored since Freud and Jung in the mid-20th century CE but was not an original thought of either of them.

His Politics addresses the concerns of the state which Aristotle sees as an organic development natural to any community of human beings. The state is not a static structure imposed on people but a dynamic, living entity created by those who then live under its rules. Long before Thomas Hobbes wrote his Leviathan concerning the burden of government or Jean-Jacque Rousseau developed his Social Contract, Aristotle had already addressed their same concerns.

Aristotle's Poetics introduced concepts such as mimesis (imitation of reality in art) and catharsis (a purging of strong emotion) to literary criticism as well as the creative arts. His observations on poetic and rhetorical form would continue to be taught as objective truths on the subject up through the period of the European Renaissance. Aristotle was naturally curious about all aspects of the human condition and natural world and systematically studied whatever subject came to his attention, learned it to his satisfaction, and then tried to make it comprehensible and meaningful through philosophical interpretation. Through this process, he developed the Scientific Method in an early form by forming a hypothesis and then testing it through an experiment which could be repeated for the same results.

Conclusion

After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, when the tide of Athenian popular opinion turned against Macedon, Aristotle was charged with impiety owing to his earlier association with Alexander and the Macedonian Court. With the unjust execution of Socrates in mind, Aristotle chose to flee Athens, "lest the Athenians sin twice against philosophy", as he said. He died of natural causes a year later in 322 BCE.

Aristotle's writings, like Plato's, have influenced virtually every avenue of human knowledge for the past two thousand years. Although he was not widely read in the west after the fall of Rome, his works were appreciated in the east where Muslim scholars drew inspiration and understanding from his works. Aristotle's Ethics (written for his son, Nichomachus, as a guide to good living) is still consulted as a philosophical touchstone in the study of ethics. He contributed to the understanding of physics, created the field and the study of what is known as metaphysics, wrote extensively on natural science and political philosophy, and his Poetics remains a classic of literary criticism.

In all this, he proved himself to be in fact The Master recognized by Dante. As with Plato, Aristotle's work infuses the entire spectrum of human knowledge as it is apprehended in the present day. Many scholars, philosophers, and thinkers over the past two thousand years have argued with, dismissed, ignored, questioned, and even debunked Aristotle's theories but none have argued that his influence was not vast and deeply penetrating, establishing schools of thought and creating disciplines taken for granted in the present as having always just existed.