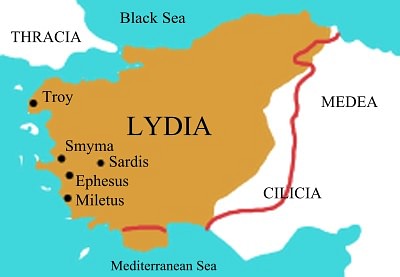

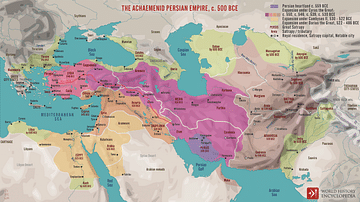

Artaphernes (active c. 513-492 BCE, also known as Artafarna) was the satrap of Lydia under the reign of his older brother Darius I (the Great, r. 522-486 BCE), monarch of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) which was founded by Cyrus II (the Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE). He is remembered for his role in the Ionian Revolt (499-494 BCE) when the Ionian Greek city-states of Asia Minor rose against Persian rule and the Battle of Sardis (498 BCE) when he defended his capital from invasion.

Artaphernes brokered a pact with ambassadors from Athens which the Persians believed made Athens subject to Persian rule. The ambassadors, however, were acting on their own when they agreed to the stipulations, which they seem to have misunderstood, and had no authority from Athens to make any such deal.

When Athens, with Eretria, supported the Ionian Revolt, some scholars claim, this was seen by Darius I as a breach of the contract the Athenians had sworn to with Artaphernes, providing further motivation for Darius I's invasion of Greece 492-490 BCE which was then followed by the invasion of Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BCE) in 480 BCE. Artaphernes was succeeded by his son, Artaphernes II (r. 492-480 BCE) who would take part in both of the later invasions of Greece in retaliation for the Ionian Revolt.

Political/Economic Background

In 522 BCE, Darius I and six other conspirators assassinated the Achaemenid king Bardiya (r. 522 BCE) claiming he was an imposter named Gaumata, a magi (priest) who had murdered the real king and taken his place. This claim is made by Darius I himself in his famous Behistun Inscription, but modern-day scholarship has challenged this version of events to suggest that Bardiya, the legitimate monarch, was deposed and killed by Darius I and his co-conspirators in a coup and the later story was created to justify their action.

Whoever Bardiya/Gaumata may have been or what his reign might have accomplished will never be known, but Darius I proved himself an efficient monarch from the start. After putting down rebellions against him, he reformed the infrastructure of the empire and appointed satraps (governors) to the various regions. The satrapy of Lydia was among the wealthiest as an important trade center and was also among the most powerful as the satrap Oroetus, who served under the king Cambyses II (r. 530-522 BCE), had defeated the Greek island state of Samos and taken their navy as his own.

After Darius I came to power, he had Oroetus executed and gave Lydia to Otanes (r. c. 522-513 BCE), one of his co-conspirators, whom he felt he could trust with such an important region. Lydia's location near the coast made it the entryway into the Achaemenid Empire for envoys from the west. Darius I, when he created his famous network of roads throughout the empire, linked the Lydian capital of Sardis with his imperial capitals of Babylon, Ecbatana, Persepolis, and Susa via the Royal Road.

Darius I had continued the policies of Cyrus the Great and Cambyses II in enlarging his empire but paid more attention than they had to creating a professional navy. The ships were built, and often manned, by the satrapy of Phoenicia and, by 513 BCE, Darius I was extending his control over Mediterranean trade and travel through this fleet and had used it to chart the coastline of mainland Greece and southern Italy, where a number of Greek colonies had been established, for future use.

At around this same time, Athens expelled the tyrant Hippias (d. c. 490 BCE) with the support of the Spartans under Cleomenes I (d. c. 489 BCE) who then established an oligarchy under Isagoras (l. late 6th century BCE). Isagoras was challenged by the Athenian statesman Cleisthenes (b. late 570s BCE) who, after an exile imposed by Isagoras, returned once the tyrant had been deposed. Cleisthenes was aware of the growing maritime power of the Achaemenids but was more concerned over the threat posed by Sparta and so sent envoys to Sardis asking for Persian support against Spartan aggression.

The Athenian Envoys

Artaphernes had succeeded Otanes as satrap of Lydia in 513 BCE but nothing is known of his reign until 507 BCE when he received the ambassadors from Athens. The details of the meeting are given by Herodotus:

Then they [the Athenians] sent a delegation to Sardis, because they knew that Cleomenes and the Lacedaemonians were up in arms against them, so they wanted to enter into an alliance with the Persians. The delegation reached Sardis and was in the middle of delivering its message when Artaphernes, who was the governor of Sardis, asked the Athenians who they were and where they were from that they sought an alliance with the Persians. The Athenian delegates gave him the information he had asked for, and then he curtly stated his position as follows: “If the Athenians give King Darius earth and water, he will enter into an alliance with them; otherwise, they will have to leave.” The delegates wanted to conclude the alliance, so of their own accord they agreed to offer the king earth and water. This got them into a lot of trouble on their return home. (V.73)

The envoys agreed to the offering of earth and water without seeming to recognize the significance of the act – which would have been understood by Artaphernes as one of submission – and so were censured upon their return to Athens; what form this censure took is unknown.

Hippias, meanwhile, had made his way to Sardis and asked Artaphernes for help in reinstating him as tyrant of Athens. According to Herodotus, Hippias did “everything he could to blacken the Athenians in the eyes of Artaphernes, and to try to find a way to get Athens within his and Darius' control” (V.96). When the Athenians received word of Hippias' activities, they sent another group of envoys to Sardis denouncing Hippias' lies.

Artaphernes, still under the impression that Athens had submitted to Persian authority, told the Athenians their future safety and security depended on their acceptance of Hippias as their ruler as this was the will of Darius I. These envoys made no reply but brought the demand back to Athens where it was rejected and so, as Herodotus says, “they had effectively decided on open hostility towards Persia” (V. 96). Persia, however, made no move on this at the time.

The Siege of Naxos

Tensions in the region remained at the same level when c. 499 BCE a group of exiled aristocrats from the island of Naxos arrived at the satrapy of Miletus requesting assistance of the deputy governor Aristagoras (d. c. 496 BCE). Aristagoras was the cousin and son-in-law of Histiaeus (d. 493 BCE), tyrant of Miletus, who had been withdrawn by Darius I to Susa, leaving Aristagoras in charge. Histiaeus had been the official in charge of placing tyrants over the cities of the Ionian Greeks in Asia Minor and had served Darius I well in the Scythian Campaign of 513 BCE. Afterwards, Darius I rewarded him with a position at Susa which Histiaeus never wanted and secretly resented.

Aristagoras received the exiles and, considering how he could control the wealthy island of Naxos through them, promised them aid if it was approved by Darius I. He then went to Artaphernes and described the plan as an easy win with minimal investment and maximum profit, saying how he was investing the money for the expedition and would succeed if Darius I would agree to supply ships and military personnel. He noted that, once they took Naxos, they would also have control of the riches of the Cyclades which were its dependents. According to Herodotus, Artaphernes welcomed the plan, proposed raising the number of ships from Aristagoras' original 100 to 200, and sent word to Darius I requesting approval, which was granted.

Darius I placed his cousin, the general Megabates (late 6th/early 5th centuries BCE), in command of the fleet who joined with Aristagoras at Miletus. The fleet sailed for Chios, where they anchored in preparation for the attack. That night, Megabates discovered that sentries had not been set on board one of the ships and punished that ship's captain, Scylax, by having him pulled through an oar-hole and tied there. Scylax was a friend of Aristagoras who demanded his release and, when Megabates refused, Aristagoras went and untied Scylax himself. Megabates was outraged and retaliated by sending word to Naxos that they were about to be attacked.

The Naxians fortified their walls and prepared for a siege while the fleet, completely unaware of the warning, sailed for the island. When they arrived, they found Naxos so well defended they could not take it and lay siege. The siege dragged on for four months, and while the Naxians were well supplied behind their walls, the expeditionary force steadily ran out of supplies and money. Aristagoras finally admitted defeat and turned the ships around for Miletus. Megabates was never censured for the Naxos campaign and was later made satrap of Phrygia.

The Ionian Revolt Begins

Aristagoras' plan had completely failed and he now had to deliver this news to Artaphernes who would, of course, inform Darius I. Aristagoras feared he would be stripped of his title – or worse – and was considering how he might extricate himself when a messenger arrived from Histiaeus at Susa. Histiaeus was careful that his message should only be read by Aristagoras and so he shaved the head of one of his slaves, had the message tattooed on the man's scalp, then waited for his hair to grow in before sending him on his mission. The message incited Aristagoras to start a rebellion in Miletus as Histiaeus was tired of being confined to Susa and thought he would be sent back to his former position if revolt broke out.

Although this version of events, as given by Herodotus, is accepted as historically accurate, the revolt Histiaeus suggested and Aristagoras started could not have gained any momentum if the Ionian Greeks had been content under Persian rule. The tyrants Histiaeus installed over the cities were only charged with keeping the peace and were otherwise free to rule as semi-autonomous petty kings. Many of the tyrants – though certainly not all – treated the people poorly to enrich themselves and, as long as peace was kept, the central Persian government left them alone to do as they pleased.

Aristagoras began the revolt by calling a meeting with those loyal to him and outlining his plan – not mentioning that he was inspired in this by his failure at Naxos and the huge sum of money he now owed Artaphernes and Darius I – and all agreed with it except the writer Hecataeus (l. c. 550 - c. 476 BCE). He then declared Miletus a democracy, free from Persian rule, and had all the tyrants of the city-states delivered to their people to be punished. Afterwards, he commandeered the ships and Greek mercenaries Artaphernes had supplied him for Naxos and used them for his newly formed rebel force.

Support from Athens & Eretria

Recognizing the need for support for his rebellion, he first turned to Sparta – who rejected him – and then to Athens who agreed to help since they had already been expecting some form of aggression from Persia after rejecting the demand they return Hippias to power. Eretria also agreed to help in the interests of maritime trade and commercial profit. The Achaemenid Empire's ships were still mainly in control of the Mediterranean and the fall of the empire would have benefited Eretria, Athens, and the Ionian Greek city-states as well as many others. Scholar Kaveh Farrokh comments on the underlying motive of the Ionian Revolt and the aid offered by Athens and Eretria:

The predominant historical view found among Western historians is that the Ionian Revolt and the Greco-Persian wars were an epic contest between democracy (as represented by Greece) and “Persian tyranny”. [The scholar] Frye cautions that, “the interpretation of…Greeks defending liberty [is] an example of imposing modern concepts on the past [and] distorting our understanding…” While the Ionian desire for independence from Achaemenid rule is a major factor that led to war, the element of economic rivalry was and equally important factor. (69)

Yet another factor was the close ties of kinship between the Athenians and the Ionians which almost guaranteed Athenian support once the revolt was launched in 499 BCE. In early 498 BCE, the Athenians sent a fleet of twenty ships and Eretria a contingent of five which joined with Aristagoras' army at Ephesus. Aristagoras refused to lead the army himself and designated his brother Charopinus and a Milesian general named Hermophantus as supreme commanders.

Battles of Sardis, Ephesus, & Lade

These generals enlisted the aid of Ephesian guides to lead them by the best way to Sardis to catch Artaphernes by surprise. Their plan worked and they were able to take the lower city but Artaphernes gathered his forces to the high ground of his citadel which he held. Scholar A. T. Olmstead describes the destruction of the lower part of the city and the ensuing Battle of Ephesus:

Sardis was a collection of reed huts or of mud-brick houses roofed with reeds; when a single house was fired by a Greek, the whole town was in flames. Trapped by the fire which destroyed the famous temple of Cybele on the Pactolus, the Persian garrison descended from the acropolis and, with the native Lydians, collected in the marketplace [to defend the city]. The allies were driven back [and] retreated toward the sea, but just before reaching Ephesus they were crushed in a great battle by Persian levies which had been raised from the various administrative divisions. (153-154)

The Battle of Ephesus was a complete victory for the Lydian-Persian forces and the Athenians barely managed to make it to their ships and escape. Aristagoras had used the same sort of speech on them as he had on Artaphernes in pitching his proposal for the taking of Naxos, claiming that the Achaemenid Empire was weak and would fall easily. Recognizing now that this was not the case, the Athenians withdrew their support and so, presumably, did Eretria.

The loss of Athens and Eretria did nothing to slow or stop the rebellion, however, and it spread from Miletus and Ephesus up and down the coast of Asia Minor. Darius I first initiated the tactic of divide-and-conquer by entering into negotiations with different city-states, promising them rewards for abandoning the cause but, failing in this, prepared his army to crush the rebellion by force. In 494 BCE, the Persians defeated the rebels at the Battle of Lade, a naval conflict off the coast of Miletus, and then systematically reduced each rebel city-state and brought them back under his control. In an effort to prevent future uprisings, he abolished the system of tyrants and granted the Ionians greater freedom.

Conclusion

Aristagoras, by this time, had been killed in a conflict with the Thracians and Histiaeus, who had been sent to the region from Susa as he had hoped, was called before Artaphernes to answer for any role he may have played in the revolt. Histiaeus claimed complete ignorance and innocence of having any part in the rebellion but Artaphernes knew he was lying and, according to Herodotus, said, “I'll tell you what actually happened in this business, Histiaeus: it was you who stitched the shoe, while Aristagoras merely put it on” (VI.1). Still, Histiaeus was trusted by Darius I and Artaphernes could do nothing to punish him.

Artaphernes later intercepted letters from Histiaeus encouraging further rebellion and had his co-conspirators killed and Histiaeus arrested. Artaphernes did not want him returned to Susa where he would have a chance to deceive Darius I into accepting his lies and had him impaled and beheaded. When Darius I received the news, he ordered that Histiaeus' head be buried with all honors as he refused to believe he had been disloyal; proving Artaphernes' sound judgment in ordering the traitor's execution.

Later in 493 BCE, Artaphernes reorganized the Ionian city-states and, on the advice of Hecataeus, pardoned the former rebel cities and treated all with leniency and justice. He disappears from the historical record after this, possibly dying in 492 BCE, and was succeeded as satrap of Lydia by his son Artaphernes II who would command part of the punitive invasion of Greece in Darius I's action of 492-490 BCE and Xerxes I's invasion of 480-479 BCE.

As the Siege of Naxos is considered the first act in the drama of the Greco-Persian Wars, and the Ionian Revolt the second, Artaphernes' involvement in both links his name forever in history with the conflict which the Greek writers would characterize as a struggle between the West and the East for ideological and political supremacy. This characterization of the Greco-Persian conflict has informed political thought, rhetoric, and policy ever since.