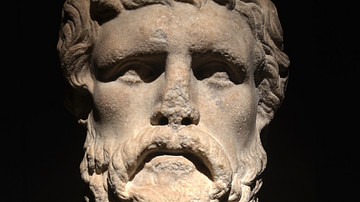

Artaxerxes II (r. 404-358 BCE, also known as Artaxerxes II Mnemon) was the 10th monarch of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE). He was the son of Darius II (r. 424-404 BCE) and Parysatis (who was Darius II's half-sister) and older brother of Cyrus the Younger (d. 401 BCE). His reign was marked by revolts beginning with that of his younger brother shortly after he came to power. Cyrus the Younger's revolt, which was crushed, was famously chronicled in the Anabasis of Xenophon (l. 430 - c. 354 BCE), commander of the Greek mercenary forces of the rebel army, who claimed Cyrus would have been the better king.

Shortly after putting down this revolt, Artaxerxes II involved himself in the Greek conflict of the Corinthian War (395-387 BCE), which accomplished nothing except empowering Athens, and then failed to put down a revolt in Egypt in 373 BCE. The failure of the Egyptian campaign led to the Great Satraps Revolt of 372-362 BCE which raged on while Artaxerxes II again involved himself in the affairs of Greece in trying to mediate the Theban-Spartan War (368-366 BCE).

He devoted significant resources to building projects, especially temples, and may have encouraged the cult of the goddess Anahita; leading some scholars to suggest he was not a Zoroastrian, as assumed by early scholars of the period, and this may have encouraged the lack of stability in his reign since is satraps (regional governors) most likely were. He died of natural causes and was succeeded by his son Artaxerxes III (r. 358-338 BCE) whose reign was even more unstable and ended with his assassination.

Although some scholars have marked the reign of Xerxes I (486-465 BCE) as the beginning of the decline of the Achaemenid Empire – noting his depletion of the treasury in his 480 BCE invasion of Greece and his poor performance afterwards – this claim ignores the effective reign of his successor Artaxerxes I (465-424 BCE). It seems far more evident that the empire began to decline under Artaxerxes II and the instability contributed to the fall of the Achaemenid Empire to Alexander the Great in 330 BCE.

Background, Rise to Power, & Revolt

Artaxerxes I had one son with his queen Damaspia, the future Xerxes II (r. 424 BCE) but many other children with his concubines. Among these were Sogdianus (r. 424 BCE), Darius II (r. 424-404 BCE) and Parysatis (l. 5th century BCE). When Artaxerxes I died, his legitimate heir Xerxes II succeeded him and reigned for just over a month before he was assassinated by Sogdianus. Sogdianus then ruled for six months before he was assassinated by his half-brother Nochus who took the throne name Darius II. Parysatis married Darius II and had a number of children with him, including Artaxerxes II and Cyrus the Younger.

When Darius II fell ill in 404 BCE, Parysatis argued that he should name Cyrus the Younger his successor because, even though Artaxerxes II was older, he had been born before Darius II was king while Cyrus the Younger had been born of the royal couple. Darius II dismissed this argument and chose his elder son to rule. Artaxerxes II, either before or after this event, married the noblewoman Stateira (d. c. 400 BCE) who would bear his heir Artaxerxes III. Parysatis, although she outwardly acknowledged her elder son as king, encouraged her younger, and favorite, son to assassinate him.

As part of a king's coronation (according to Ctesias, l. 5th century BCE, and others), he had to travel to Pasargadae, the capital of Cyrus the Great (founder of the Achaemenid Empire, r. c. 550-530 BCE), enter a temple (most likely the temple of Anahita), take off his clothes, and dress in those belonging to Cyrus, and then eat and drink in a symbolic ritual. Artaxerxes II was alerted by his general Tissaphernes (satrap of Caria, l. 445-395 BCE), that Cyrus the Younger was waiting (or planning to wait) inside the temple for Artaxerxes II to begin removing his clothes and then kill him. Artaxerxes II ordered Cyrus the Younger's imprisonment to await execution, but Parysatis intervened and had her son returned to his position as satrap in Asia Minor.

Xenophon claims Tissaphernes lied about Cyrus the Younger's intentions, noting Cyrus' noble character and personal integrity, and defends his later revolt as a response to his public humiliation of arrest and imprisonment:

Cyrus had been humiliated and had come close to losing his life, so once he was back in his province he began to make plans; he wanted never again to be in his brother's power, and he wanted, if he could, to rule in his place. (Anabasis, I.1)

After he had been restored to his satrapy, Cyrus the Younger began building an army, claiming he was going to campaign against the tribes of Pisidia, and sent out a request for Greek mercenaries to join him. One of the Greek leaders who answered this call was Xenophon, a former student of Socrates (d. 399 BCE), who arrived with a large force. Tissaphernes was sure Cyrus the Younger was amassing the army to depose his brother and warned Artaxerxes II of this who then began building up his own army.

Cunaxa & Parysatis

The two forces met at the Battle of Cunaxa (401 BCE). Cyrus the Younger was winning when, as he charged against his brother, he was hit in the temple by a dart (or javelin) hurled by a soldier named Mithridates (d. 401 BCE), knocking him from his horse. According to most reports, this killed him although there are others claiming he was then killed with a stone or a second dart. Cyrus the Younger's troops then scattered and Xenophon, along with his 10,000 Greek mercenaries, found himself on the losing side of the battle in a foreign country with no way home. His account of the conflict, and how he led his troops through hostile territory and back to Greece, is told in his Anabasis.

Artaxerxes II wanted his troops to believe that he had killed Cyrus the Younger himself and so bribed Mithridates to keep quiet while the king received the glory for the kill and the victory. Mithridates was rewarded for his silence with fine clothes, jewels, and a sword allegedly for bringing Artaxerxes II the tack from Cyrus' horse. It seems few people believed this story, however, and at a banquet, Mithridates was asked how it was that simply bringing the king some trappings from Cyrus' horse had won him such gifts. Mithridates was drunk and told the company – which included palace eunuchs of both Artaxerxes II and Parysatis – how he had killed Cyrus, not the king. Artaxerxes II was outraged and had Mithridates executed by scaphism.

Another version of the story has Parysatis decree the death of Mithridates. Parysatis remained as influential a figure in Artaxerxes II's court as she had been during the reign of Darius II. She had spies everywhere who kept her well-informed and enhanced her influence. She is said to have executed anyone who had any connection to the death of her favorite son but could not kill the king himself; so she did the next best thing.

She recognized that the only person Artaxerxes II truly loved was his wife Stateira with whom she already had a very public rivalry as both women tried their best to control the king. Artaxerxes II was aware of the enmity between his mother and wife and, when they dined together, made sure both of them were served the same food from the same vessels so that neither could poison the other. Parysatis got around this, allegedly, by having her servant Gigis carve a half of the roasted bird for the dinner with a poisoned knife and the other with a different blade. The poisoned part was served to Stateira, killing her. Artaxerxes II had Gigis executed and banished his mother but later relented and allowed her to return to court. Parysatis' eventual fate is unknown.

Campaigns in Greece & Egypt

Shortly after this, Artaxerxes II involved himself in the affairs of Greece during the Corinthian War between Sparta and a coalition of the city-states of Argos, Athens, Corinth, and Thebes. The underlying cause of the war was the new expansionist policies of Sparta which alarmed the other Greek cities, especially after Sparta's recent victory over Athens in the Second Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE). Artaxerxes II backed the allies in this against Sparta.

Sparta began the conflict from a position of strength but, funded by the vast wealth of the Achaemenid Empire, the allies began to score a number of significant victories. Athens was able to revitalize and reequip its navy and took back territories lost to Sparta earlier. As Athens grew stronger, Artaxerxes II realized he may have made a mistake and switched sides in support of Sparta. The opposing forces then stopped the conflict and asked Artaxerxes II to mediate a treaty, resulting in the King's Peace (also known as the Peace of Antalkidas, after the Spartan diplomat to Artaxerxes II's court) of 387/386 BCE.

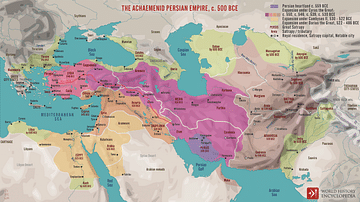

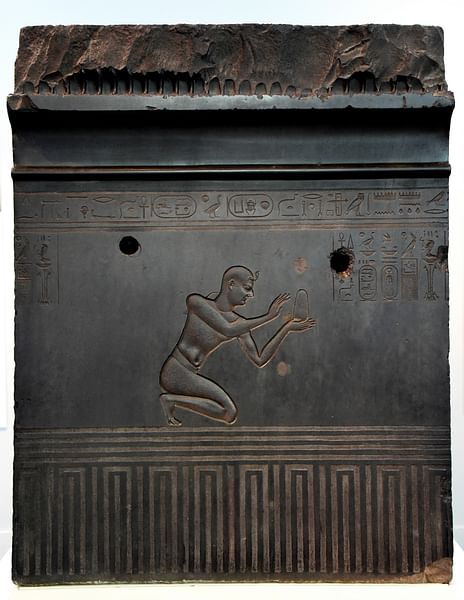

While Artaxerxes II had been busying himself with the war in Greece, the Persian satrapy of Egypt was breaking away. The Persian king Cambyses II (r. 530-522 BCE) had taken Egypt into the empire in 525 BCE following the Battle of Pelusium but Egypt had rebelled under the past two of Artaxerxes II's predecessors – as recently as 405 BCE under Darius II – and Artaxerxes II should have been paying more notice. Lower Egypt had already been lost and the Persians only held Upper Egypt. An Egyptian noble of Lower Egypt, Nectanebo I (r. c. 379-363 BCE), came to power and founded the 30th Dynasty of Egypt, modeling himself on the great Egyptian kings of the past and declaring Egyptian independence.

It was not until 373 BCE that Artaxerxes II took action and launched 12,000 troops, made up of Persian regulars and Greek mercenaries, to put down the revolt. The army was commanded by the Greek general Iphicrates and Persian satrap and general Pharnabazus, who each had their own idea on how the campaign should operate. Nectanebo I heavily fortified the city of Pelusium and the shores of the Nile, which forced the advancing Persian forces into a more difficult branch of the river near the city of Mendes, which would make for a longer journey to reach the goal of the city of Memphis. Even though Memphis was no longer Egypt's capital, it still had great symbolic resonance and was the first the Persians planned on reducing.

By the time the Persians navigated their way close to Memphis, Iphicrates and Pharnabazus were in conflict and Memphis was so heavily fortified that it could not be taken. The Egyptian campaign was a failure and the Persian army returned home. Artaxerxes II then replaced Pharnabazus with the satrap of Cappadocia Datames (l. c. 407 - c. 362 BCE) and ordered him to complete the campaign, but Datames decided to use the army to depose Artaxerxes II instead.

The Great Satraps Revolt & Mediation in Greece

The failure of the Egyptian campaign emboldened a number of satraps who were already dissatisfied with the reign of Artaxerxes II. Datames felt he was being treated poorly by Artaxerxes II in being asked to lead a campaign that had already failed. Instead of marching on Nectanebo I, he accepted support from him to turn on the Persian king. He was killed in action in 362 BCE but the revolt was continued by the Persian governor of Phrygia, Ariobarzanes (d. 362 BCE), who led the rebels until he was betrayed by his son and crucified.

The revolt posed a serious threat to the throne, not only because the governors who were supposed to protect and defend the king were now attacking him, but because the rebels were backed by almost all of Asia Minor, Egypt, and Sparta. Without the support of the satraps, the central Persian government was weakened. Artaxerxes II – like the Achaemenid kings before him – relied on his satraps to provide troops in times of crisis and now those troops were turned against him.

His reign was preserved, not by any decisive action he took, but by the lack of unity among the rebels. One of the best-known examples of this is the case of Mausolus, satrap of Caria (r. 377-353 BCE), famous for his Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world. Mausolus, who remained loyal to Artaxerxes II but seemed to support the rebellion at one point, used the other satraps for his own benefit. He requested funds from the rebel satraps to build a defensive wall, claiming imminent need and, once he had the money, said he had heard from the gods that the time was wrong for building the wall and then deposited the donations in his private account.

There is no report that any of the other satraps called Mausolus to answer for this, which epitomizes the underlying problem of the revolt: there was no central command which could have responded to Mausolus' trickery or any other betrayal of the cause. Each satrap who joined Datames' initial revolt did so out of self-interest, and this remained the model throughout the rebellion. The betrayal of Ariobarzanes by his son is only one example of this. After Ariobarzanes' death, one Aroandas took the leadership and betrayed the rebels to Artaxerxes II who crushed them. Nectanebo II found himself involved with his own troubles in Egypt, and so never sent the promised troops for support, and Sparta was engaged in the Theban-Spartan War, withdrew their aid, and the rebellion failed.

Artaxerxes II wisely decided not to punish the rebel satraps, fearing this would lead to another revolt he might not survive, and pardoned them all. He had earlier, again, involved himself in the wars of Greece, outlining a peace treaty which favored Thebes, which was rejected and did nothing to strengthen his authority.

Building Projects & Religion

When he was not interfering in the affairs of Greece, Artaxerxes II engaged in a number of building projects, not only his well-known contributions to Persepolis and Susa, but temples to the goddess Anahita throughout the empire. His buildings included inscriptions asking for the protection of Ahura Mazda, Anahita, and Mithra which some scholars argue supports the claim that Zoroastrianism was a polytheistic faith and these three deities served as a kind of Zoroastrian Trinity. This claim is unsupported by any evidence, however, as Zoroastrianism was founded as a monotheistic religion.

The prophet Zoroaster (c. 1500-1000 BCE) founded his religion in opposition to the polytheism of the Early Iranian Religion after receiving a vision from Ahura Mazda as the one true god. Ahura Mazda had earlier been the king of the gods in the Iranian pantheon but, according to Zoroaster's vision, was actually the sole deity and all the others simply emanations and aspects of him. Zoroastrianism was well-established by the time the Achaemenid Empire was founded c. 550 BCE and so early scholars and archaeologists studying this period assumed the Achaemenid kings from Cyrus the Great onwards were Zoroastrians. This conclusion has since been challenged, however, since the inscriptions of Cyrus and Darius I (r. 522-486 BCE), at least, can be interpreted as referencing the earlier polytheistic religion as easily as Zoroastrianism.

It is quite likely that Artaxerxes II was not a Zoroastrian as evidenced by the number of temples erected to Anahita under his reign. Anahita was among the most popular goddesses of the earlier religion, presiding over fertility, water, health and healing, wisdom, and war. The historian Berosus (3rd century BCE) claims that Artaxerxes II was the first Achaemenid monarch to erect statues of Anahita in temples in the major cities of the empire. This suggests the king's support of a cult of Anahita whose popularity under his reign was more widespread than under his predecessors. If Artaxerxes II did, in fact, support the earlier polytheistic religion – or at least a cult following of Anahita - it might account for the lack of support from the satraps, many of whom were most likely, or certainly, Zoroastrians.

Conclusion

The reign of Artaxerxes II was troubled from the start and never really stabilized following the rebellion of Cyrus the Younger. Xenophon, in his Anabasis, claims that Cyrus the Younger was more fit to be king, writing:

Of all the successors of [Cyrus the Great], no Persian was a more natural ruler and none more deserved to rule. This was the view of all who were held to have been close to Cyrus…he demonstrated, first, that the quality he held most important when he was making a treaty or entering into a contract or making a promise was his own personal integrity. This is why the cities trusted him and put themselves into his hands and why individuals trusted him too. (I.9)

Artaxerxes II was chosen to rule over Cyrus the Younger, not on merit, but simply because he was the older brother. His reign marked no significant advances in Persian culture and its lack of stability would continue through the reigns of his successors. By the time Alexander the Great invaded in 334 BCE, although the empire was still intact, it lacked the cohesion of the reigns of the kings from Cyrus the Great to Artaxerxes I and no longer had the strength it would have needed to save itself from falling to the Macedonians.