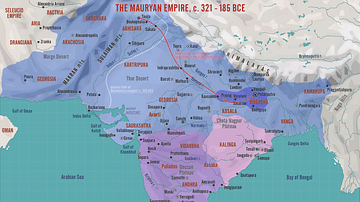

Ashoka the Great (r. 268-232 BCE) was the third king of the Mauryan Empire (322-185 BCE) best known for his renunciation of war, development of the concept of dhamma (pious social conduct), and promotion of Buddhism as well as his effective reign of a nearly pan-Indian political entity.

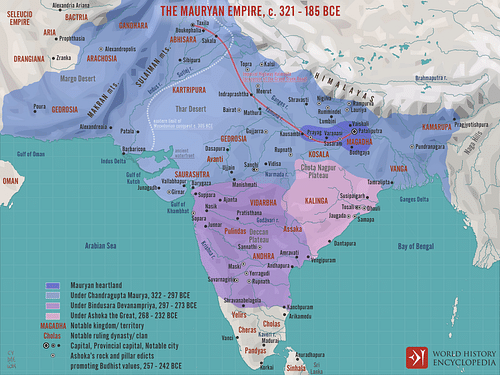

At its height, under Ashoka, the Mauryan Empire stretched from modern-day Iran through almost the entirety of the Indian subcontinent. Ashoka was able to rule this vast empire initially through the precepts of the political treatise known as the Arthashastra, attributed to the Prime Minister Chanakya (also known as Kautilya and Vishnugupta, l. c. 350-275 BCE) who served under Ashoka's grandfather Chandragupta (r. c. 321-c.297 BCE) who founded the empire.

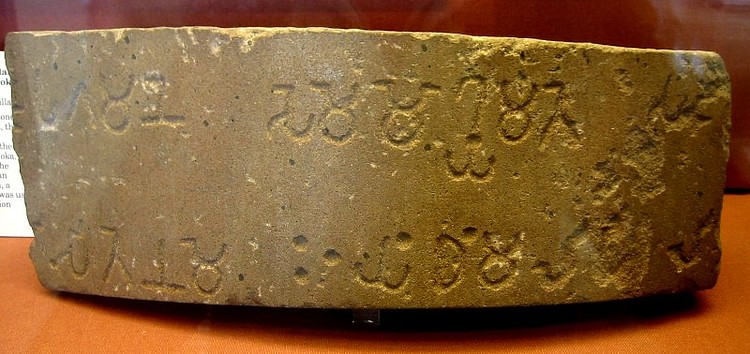

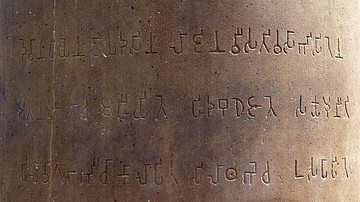

Ashoka means “without sorrow” which was most likely his given name. He is referred to in his edicts, carved in stone, as Devanampiya Piyadassi which, according to scholar John Keay (and agreed upon by scholarly consensus) means “Beloved of the Gods” and “gracious of mien” (89). He is said to have been particularly ruthless early in his reign until he launched a campaign against the Kingdom of Kalinga in c. 260 BCE which resulted in such carnage, destruction, and death that Ashoka renounced war and, in time, converted to Buddhism, devoting himself to peace as exemplified in his concept of dhamma. Most of what is known of him, outside of his edicts, comes from Buddhist texts which treat him as a model of conversion and virtuous behavior.

The empire he and his family built did not last even 50 years after his death. Although he was the greatest of the kings of one of the largest and most powerful empires in antiquity, his name was lost to history until he was identified by the British scholar and orientalist James Prinsep (l. 1799-1840 CE) in 1837 CE. Since then, Ashoka has come to be recognized as one of the most fascinating ancient monarchs for his decision to renounce war, his insistence on religious tolerance, and his peaceful efforts in establishing Buddhism as a major world religion.

Early Life & Rise to Power

Although Ashoka's name appears in the Puranas (encyclopedic literature of India dealing with kings, heroes, legends, and gods), no information on his life is given there. The details of his youth, rise to power, and renunciation of violence following the Kalinga campaign come from Buddhist sources which are considered, in many respects, more legendary than historical.

He was highly educated at court, trained in martial arts, and was no doubt instructed in the precepts of the Artashastra – even if he was not considered a candidate for the throne – simply as one of the royal sons. The Artashastra is a treatise covering many different subjects related to society but, primarily, is a manual on political science providing instruction on how to rule effectively. It is attributed to Chanakya, Chandragupta's prime minister, who chose and trained Chandragupta to become king. When Chandragupta abdicated in favor of Bindusara, the latter is said to have been trained in the Arthashastra and so, almost certainly, would have been his sons.

When Ashoka was around the age of 18, he was sent from the capital city of Pataliputra to Takshashila (Taxila) to put down a revolt. According to one legend, Bindusara provided his son with an army but no weapons; the weapons were provided later by supernatural means. This same legend claims that Ashoka was merciful to the people who lay down their arms upon his arrival. No historical account survives of Ashoka's campaign at Taxila; it is accepted as historical fact based on suggestions from inscriptions and place names but the details are unknown.

She was not apparently married to Ashoka nor destined to accompany him to Pataliputra and become one of his queens. Yet she bore him a son and a daughter. The son, Mahinda, would head the Buddhist mission to Sri Lanka; and it may be that his mother was already a Buddhist, thus raising the possibility that Ashoka was drawn to the Buddha's teachings [at this time]. (90)

According to some legends, Devi first introduced Ashoka to Buddhism, but it has also been suggested that Ashoka was already a nominal Buddhist when he met Devi and may have shared the teachings with her. Buddhism was a minor philosophical-religious sect in India at this time, one of the many heterodox schools of thought (along with Ajivika, Jainism, and Charvaka) vying for acceptance alongside the orthodox belief system of Sanatan Dharma (“Eternal Order”), better known as Hinduism. The focus of the later chronicles on Ashoka's affair with the beautiful Buddhist Devi, rather than on his administrative accomplishments, can be explained as an effort to highlight the future king's early association with the religion he would make famous.

Ashoka was still at Ujjain when Taxila rebelled again and Bindusara this time sent Susima. Susima was still engaged in the campaign when Bindusara fell ill and ordered his eldest son's recall. The king's ministers, however, favored Ashoka as successor and so he was sent for and was crowned (or, according to some legends crowned himself) king upon Bindusara's death. Afterwards, he had Susima executed (or his ministers did) by throwing him into a charcoal pit where he burned to death. Legends also claim he then executed his other 99 brothers but scholars maintain he killed only two and that the youngest, one Vitashoka, renounced all claim to rule and became a Buddhist monk.

The Kalinga War & Ashoka's Renunciation

Once he had assumed power, by all accounts, he established himself as a cruel and ruthless despot who pursued pleasure at his subjects' expense and delighted in personally torturing those who were sentenced to his prison known as Ashoka's Hell or Hell-on-Earth. Keay, however, notes a discrepancy between the earlier association of Ashoka with Buddhism through Devi and the depiction of the new king as a murderous fiend-turned-saint, commenting:

Buddhist sources tend to represent Ashoka's pre-Buddhist lifestyle as one of indulgence steeped in cruelty. Conversion then became all the more remarkable in that by `right thinking' even a monster of wickedness could be transformed into a model of compassion. The formula, such as it was, precluded any admission of Ashoka's early fascination with Buddhism and may explain the ruthless conduct attributed to him when Bindusara died. (90)

This is most likely true but, at the same time, may not be. That his policy of cruelty and ruthlessness was historical fact is borne out by his edicts, specifically his 13th Major Rock Edict, which addresses the Kalinga War and laments the dead and lost. The Kingdom of Kalinga was south of Pataliputra on the coast and enjoyed considerable wealth through trade. The Mauryan Empire surrounded Kalinga and the two polities evidently prospered commercially from interaction. What prompted the Kalinga campaign is unknown but, in c. 260 BCE, Ashoka invaded the kingdom, slaughtering 100,000 inhabitants, deporting 150,000 more, and leaving thousands of others to die of disease and famine.

Afterwards, it is said, Ashoka walked across the battlefield, looking upon the death and destruction, and experienced a profound change of heart which he later recorded in his 13th Edict:

On conquering Kalinga, the Beloved of the Gods [Ashoka] felt remorse for, when an independent country is conquered, the slaughter, death, and deportation of the people is extremely grievous to the Beloved of the Gods and weighs heavily on his mind…Even those who are fortunate to have escaped, and whose love is undiminished, suffer from the misfortunes of their friends, acquaintances, colleagues, and relatives…Today, if a hundredth or a thousandth part of those people who were killed or died or were deported when Kalinga was annexed were to suffer similarly, it would weigh heavily on the mind of the Beloved of the Gods. (Keay, 91)

Ashoka then renounced war and embraced Buddhism but this was not the sudden conversion it is usually given as but rather a gradual acceptance of Buddha's teachings which he may, or may not, have already been acquainted with. It is entirely possible that Ashoka could have been aware of Buddha's message before Kalinga and simply not taken it to heart, not allowed it to in any way alter his behavior. This same paradigm has been seen in plenty of people – famous kings and generals or those whose names will never be remembered – who claim to belong to a certain faith while regularly ignoring its most fundamental vision.

It is also possible that Ashoka's knowledge of Buddhism was rudimentary and that it was only after Kalinga, and a spiritual journey through which he sought peace and self-forgiveness, that he chose Buddhism from among the other options available. Whether the one or the other, Ashoka would embrace Buddha's teachings in so far as he could as a monarch and establish Buddhism as a prominent religious school of thought.

The Path of Peace & Criticism

According to the accepted account, once Ashoka embraced Buddhism, he embarked on a path of peace and ruled with justice and mercy. Whereas he had earlier engaged in the hunt, he now went on pilgrimage and while formerly the royal kitchen slaughtered hundreds of animals for feasts, he now instituted vegetarianism. He made himself available to his subjects at all times, addressed what they considered wrongs, and upheld the laws which benefited all, not only the upper class and wealthy.

This understanding of Ashoka's post-Kalinga reign is given by the Buddhist texts (especially those from Sri Lanka) and his edicts. Modern-day scholars have questioned how accurate this depiction is, however, noting that Ashoka did not return the kingdom to the survivors of the Kalinga campaign nor is there any evidence he called back the 150,000 who had been deported. He made no effort at disbanding the military and there is evidence that military might continued to be used in putting down rebellions and maintaining the peace.

All of these observations are accurate interpretations of the evidence but ignore the central message of the Artashastra, which would have essentially been Ashoka's training manual just as it had been his father's and grandfather's. The Artashastra makes clear that a strong State can only be maintained by a strong king. A weak king will indulge himself and his own desires; a wise king will consider what is best for the greatest number of people. In following this principle, Ashoka would not have been able to implement Buddhism fully as a new governmental policy because, first of all, he needed to continue to present a public image of strength and, secondly, most of his subjects were not Buddhist and would have resented that policy.

Ashoka could have personally regretted the Kalinga campaign, had a genuine change of heart, and yet still have been unable to return Kalinga to its people or reverse his earlier deportation policy because it would have made him appear weak and encouraged other regions or foreign powers toward acts of aggression. What was done, was done, and the king moved on having learned from his mistake and having determined to become a better man and monarch.

Conclusion

Ashoka's response to warfare and the tragedy of Kalinga was the inspiration for the formulation of the concept of dhamma. Dhamma derives from the concept, originally set down by Hinduism, of dharma (duty) which is one's responsibility or purpose in life but, more directly, from Buddha's use of dharma as cosmic law and that which should be heeded. Ashoka's dhamma includes this understanding but expands it to mean general goodwill and beneficence to all as “right behavior” which promotes peace and understanding. Keay notes that the concept is equated with “mercy, charity, truthfulness, and purity” (95). It is also understood to mean “good conduct” or “decent behavior”.

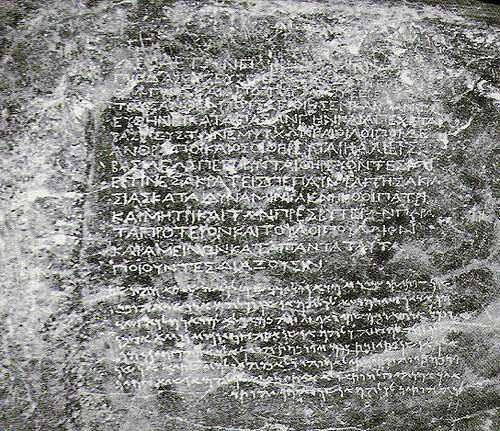

After he had embraced Buddhism, Ashoka embarked on pilgrimages to sites sacred to Buddha and began to disseminate his thoughts on dhamma. He ordered edicts, many referencing dhamma or explaining the concept fully, engraved in stone throughout his empire and sent Buddhist missionaries to other regions and nations including modern-day Sri Lanka, China, Thailand, and Greece; in so doing, he established Buddhism as a major world religion. These missionaries spread Buddha's vision peacefully since, as Ashoka had decreed, no one should elevate their own religion over anyone else's; to do so devalued one's own faith by supposing it to be better than another's and so lost the humility necessary in approaching sacred subjects.

Ashoka died after reigning for nearly 40 years. His reign had enlarged and strengthened the Mauryan Empire and yet it would not endure for even 50 years after his death. His name was eventually forgotten, his stupas became overgrown, and his edicts, carved on majestic pillars, toppled and buried by the sands. When European scholars began exploring Indian history in the 19th century, the British scholar and orientalist James Prinsep came across an inscription on the Sanchi stupa in an unknown script which, eventually, he came to understand as referencing a king by the name of Devanampiya Piyadassi who, as far as Prinsep knew, was referenced nowhere else.

In time, and through the efforts of Prinsep in deciphering Brahmi Script as well as those of other scholars, it was understood that the Ashoka named as a Mauryan king in the Puranas was the same as this Devanampiya Piyadassi. Prinsep published his work on Ashoka in 1837 CE, shortly before he died, and the great Mauryan king has since attracted increasing interest around the world; most notably as the only empire-builder of the ancient world who, at the height of his power, renounced warfare and conquest to pursue mutual understanding and harmonious existence as both domestic and foreign policy.