The meeting of the Assembly of Notables in 1787 was a last-ditch effort by the ministers of King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) to fix the disastrous condition of French finances. The assembly failed to agree on a series of radical financial reforms and insisted on convening the Estates-General, a representative body, which alone had the authority to consider reforms.

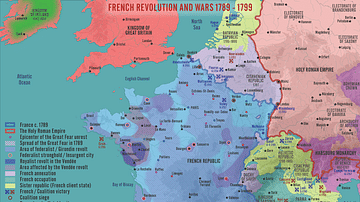

The Assembly of Notables was called at the behest of Charles Alexandre de Calonne (1734-1802), the latest in a long string of finance ministers to Louis XVI. Calonne, who sought to bypass the authority of the troublesome parlements, hoped that an assembly of 144 handpicked notables would lend enough legitimacy to his reforms to force the parlements to register them in their respective jurisdictions. What Calonne had not counted on was that several factors, including his own deep unpopularity, would turn the notables against his reforms. When the assembly claimed it had no authority to accept any reforms at all, Louis XVI had no choice but to call a meeting of the Estates-General in 1789, the event that triggered the French Revolution (1789-1799).

A Crown in Crisis

When Charles Alexandre de Calonne came to his office as Controller-General of Finances in late 1783, he found himself faced with quite the mess. The recent French involvement in the American Revolution, the latest in a century's worth of expensive military endeavors, combined with a disjointed system of taxation to send the state rapidly hurtling toward bankruptcy and financial ruin. It was therefore Calonne's unenviable task to succeed where his predecessors, Anne-Robert Jacques Turgot and Jacques Necker, had failed. Still, it appeared Calonne was confident in his abilities. When Queen Marie Antoinette (l. 1755-1793) told him that his task appeared to be one of great difficulty, Calonne responded, "if it is but difficult, it is done; if it is impossible, it shall be done"(Carlyle, 62).

Alongside his patron, the powerful Comte de Vergennes (1719-1787), Chief Minister of France, Calonne worked to plan the reforms that he hoped would save the kingdom. What he came up with, in the words of historian William Doyle, proved to be "the most radical and comprehensive plan of reform in the monarchy's history" (Doyle, 68). The plan involved aspects of proposals that had been tried before; for instance, Calonne called for the elimination of restrictions on the grain trade, a policy that had been attempted by one of his predecessors, Anne-Robert Jacques Turgot, and had resulted in the Flour War riots of 1775. Yet coupled with other proposals, such as the abolition of internal customs barriers and the conversion of the corvée (a system of unpaid labor) into a money tax, Calonne was convinced these measures could stimulate France's stifled economy.

The heart and soul of Calonne's reform plan was in his proposed land value tax. This tax was to act as a replacement of the vingtième (twentieth) tax and was designed to circumvent the privileges of the clergy and nobility and get them to pay their fair share. While the vingtième taxed 5% of an individual's net earnings, Calonne's land tax would be levied against landowners based on the value of their landholdings. Such a tax would be overseen by new provincial assemblies that would be comprised of taxpayers themselves. Calonne estimated that his land value tax would bring in 35 million more livres than the existing vingtième.

To summarize, Calonne's financial reform plan was fivefold:

- To implement a general land tax, applicable to all landowners in France, designed to circumvent the tax-exempted privileges of the upper classes

- To convert the corvée labor system into a money tax

- Abolish all internal tariffs

- Abolish restrictions on the grain trade

- The creation of provincial assemblies made up of elected taxpayers

Opposition to the Plan

When Calonne officially presented his plan to the king in August 1786, he may have expected a warm reception. After all, in the words of his assistant and soon-to-be bishop Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, the plan was "more or less the result of all that good minds have been thinking for several years" (Doyle, 71). Yet Calonne was to face several significant obstacles before he could implement his reforms. The first of these was the anticipated resistance of the parlements, France's 13 judicial courts. Although these courts were not legislative bodies, any royal edict had to be registered by a parlement before it could go into effect within the parlement's jurisdiction. In recent years, the parlements had become engaged in a power struggle with royal authority, especially when it came to financial reforms. Since the leaders of the parlements, nobles and wealthy bourgeoisie, were at risk of losing some of their privileges should Calonne's reforms go into effect, he found it doubtful that they would welcome his plans with open arms.

The second major obstacle to Calonne's reforms was his own reputation. In 1786, the national deficit reached massive heights, coming to approximately 112 million livres. Calonne's opponents argued that this was much higher, during a time of peace, than it had been during the American War, and concluded that Calonne was an irresponsible spendthrift who should not be trusted with the state's finances. This ignored the fact that much of Calonne's spending was made to simply keep the kingdom afloat, and that the Controller-General was currently facing the financial consequences of France's participation in the war, in the form of the outstanding loans he had to pay. The man who had taken out those loans, Jacques Necker (1732-1804), was one of Calonne's biggest critics. Having resigned from the king's cabinet five years before, Necker made his triumphant return to Paris in 1786, after public opinion of the government had hit rock bottom in the wake of the affair of the diamond necklace. While Calonne and the king were despised by the public, Necker, a Protestant commoner from Geneva, was more popular than ever.

Necker's popularity was rooted in his publication of the Compte Rendu au Roi (Report to the king) in 1781, the first instance of royal finances made public. This report claimed a low national deficit during Necker's years as Director of Finances during the height of the American War, something that Calonne later disputed, claiming that a 40 million livre deficit had been hidden from the report in the year of its publication. In any event, the simple facts were that Necker was popular and Calonne was not, giving Necker's critiques more validation in the public's eyes, and making the attacks against Calonne all the more impactful. Before long, pamphlets were being circulated that called Calonne 'Monsieur Deficit', comparing him with the queen, another widely hated spendthrift who had long been known as 'Madame Deficit.'

With these two obstacles working against him, Calonne saw only two ways he could bypass the authority of the parlements to implement his reforms. One solution was to call a meeting of the Estates-General, a representative body comprised of the three estates of pre-revolutionary France: the clergy, nobility, and commoners, but Calonne and the king considered this a risky move. The Estates-General had not been convened since 1614, and as such, calling one to order was seen as too unpredictable. To Calonne's mind, the safer route was the second option available to him, which was calling an Assembly of Notables.

Like the Estates-General, the Assembly of Notables was an ancient institution that had not been called in over a century. Yet, working in Calonne's favor, each notable would be a distinguished figure handpicked by the Crown. This was much preferable to the elected deputies of an Estates-General. Calonne believed that an Assembly of Notables would rubber-stamp his reforms without much debate and that the approval of a body of the most illustrious men in France would give the parlements no choice but to register the reforms. However, Calonne was soon to learn it would not be as smooth as all that, for, as historian Simon Schama put it, it would be "Calonne, not the debt, that would be sunk by 1787" (235).

The Assembly Convenes

King Louis XVI announced the meeting of an assembly on 29 December 1786 and scheduled it for January of the next year. However, the assembly did not meet until February, on account of both Calonne and his patron Vergennes coming down with violent fevers. While Calonne eventually recovered, Vergennes did not, and his death on 13 February meant that Calonne was deprived of his most powerful ally when he needed him most.

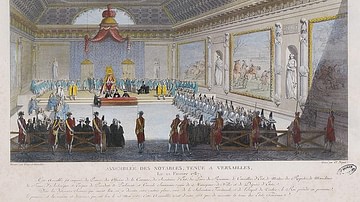

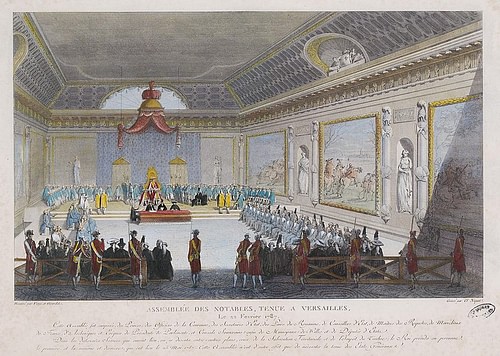

The Assembly of Notables met in Versailles on 22 February 1787. Off the 144 selected notables, all but five were nobles, including seven princes of the blood, numerous dukes and marshals, and presidents of the parlements. Members included future revolutionary leaders such as Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834), who had already built himself a reputation as a freedom fighter and a hero of the American Revolutionary War. Although Necker himself was not amongst the notables, enough of his supporters were present to make trouble for Calonne.

Calonne opened the assembly with a speech attacking Necker, stating that the Crown had borrowed no less than 1,250 million livres since 1776 to create a powerful navy and wage the war against Britain. Such actions had become self-defeating and resulted in abuses, such as increasing confusion between private and public finances and unjustifiable tax exemptions accorded to certain individuals. In answer to these problems, which would bring about the ruin of France if left undealt with, Calonne announced the details of his own reform plan.

Far from the immediate acceptance Calonne had anticipated, the notables pushed back against the plan. It has been traditionally thought that this disagreement stemmed from the notables' desire to retain their privileges and not bear the burden of Calonne's land tax. However, historian Simon Schama claims that many of the notables believed strongly in financial reform, with some even believing that the suggested reforms did not go far enough. Lafayette, for example, wanted to transfer oversight of all taxation to the proposed provincial assemblies, not just Calonne's land tax. Other notables argued for a levy on the net product of the land once costs of seed and labor had been deducted. In Schama's view, the problem the notables had was not with the idea of ceding some of their privileges but, instead, with Calonne and his methods. Of course, the traditional view still also holds merit, as other notables were not willing to take on taxation burdens that had historically fallen on the shoulders of the commoners, the Third Estate.

Over the coming days, the assembly continued to argue and made so little progress that Lafayette wrote to his friend Thomas Jefferson, wondering if the group should not instead call themselves an assembly of "Not Ables" (Fraser, 248). As the days turned to weeks and the weeks turned to months, the king began to become increasingly impatient. Facing the prospect of national bankruptcy, Louis XVI quickly became depressed. He would show up weeping to Marie Antoinette's apartments and took far longer than usual on his hunts before gorging himself on large dinners, unusual behavior even for his appetite. The public, along with the scathing and slanderous libelle pamphlets, got wind of the change in the king's behavior, and rumors started to circulate that he had become a drunkard.

As the king sulked, the assembly stalled. On 3 March, someone made the first overt claim that an Assembly of Notables had no authority to discuss issues of taxation and that an Estates-General must be called. It was at this point that the assembly truly began to unravel. The Comte de Mirabeau, hardly a paragon of virtue himself, discovered that Calonne had engaged in shady stock-exchange dealings in his past, something that Calonne's enemies latched onto, demanding he release full financial accounts. By April, the proceedings of the assembly, which were supposed to largely be kept secret, had been leaked to the public, and the chorus for both an Estates-General and the removal of Calonne grew louder.

On 8 April, Louis XVI seemed to show support for Calonne by dismissing his Keeper of Seals, Armand de Miromesnil, who had long been one of Calonne's staunchest opponents. This show of support did not last long, as later that same day, the king dismissed Calonne himself. The king, becoming increasingly desperate, clearly determined that Calonne was too much of a liability to pass any reforms. Calonne left Versailles in disgrace, traveling through the streets of Paris amidst hostile crowds that cheered his dismissal and burned him in effigy. Eventually, he made his way to Britain, where he would spend most of the rest of his life in exile.

The Rise of Brienne

With Calonne gone, Louis XVI needed to find a fresh face to pass his reforms. He found a potential savior in the person of Étienne Loménie de Brienne (1727-1794), the 60-year-old archbishop of Toulouse and a close ally of the queen. The king himself disapproved of Brienne's character, at one point saying of him that "an archbishop…must at least believe in God!" (Fraser, 253). Yet Louis was quickly running out of options, and Brienne, who had participated in the assembly as a notable and had the queen's full support, seemed the best choice.

Brienne made minor modifications to Calonne's original plan, redefining the land tax as a specific amount of money determined by the revenue needs of the state each year. The other parts of Calonne's plan were largely left unchanged. Upon unveiling this new edition of the plan to the assembly on 9 May, Brienne was soon met with similar skepticism as Calonne had endured. Many of the notables had spent the time between Calonne's fall and Brienne's rise scrutinizing accounts and insisted that the true nature of French finances must be established by a permanent commission of auditors before any further reforms could be discussed. Brienne had no objections to this idea, but the king believed it to be an infringement on his authority and vetoed it. With the royal veto, all semblance of productivity in the assembly came to an end.

Calls for an Estates-General became louder than ever, as many notables became convinced that social matters, such as the abolition of privileges allocated to certain estates, could not be discussed without the presence of representatives from all three societal orders. Many people, both within and outside the assembly, had also already decided that only the Estates-General possessed the authority to approve such sweeping financial reforms. On 21 May, Lafayette went even further and urged the Crown to go beyond an Estates-General and convene a national assembly, in which individual representatives would each receive one vote, rather than the method of an Estates-General in which entire estates only had one vote each. If an Estates-General had sounded risky to the king, a national assembly was certainly out of the question.

By now, it was apparent the Assembly of Notables was not going to come to a useful conclusion, and Brienne dissolved the assembly on 25 May. In his closing speech, he announced his intention to press on with his modified version of the financial reforms, by taking them to the parlements. If Brienne had believed the parlements would view him in a better light than they had viewed Calonne, he was mistaken. Far from registering his reforms, the parlements joined their voices to the ever-growing chorus calling for an Estates-General. When the frustrated king issued a lit de justice, which was supposed to have enforced a royal decree regardless of parlement approval, the parlements declared this to be illegal, beginning another struggle between royal and parlement authority, the Rebellion of the Parlements (1787). This struggle only ended in 1788, with Brienne's resignation, Necker's reinstatement, and a royal promise that an Estates-General would be summoned in 1789.

Conclusion

The failure of the Assembly of Notables to agree on Calonne's reforms showed how broken France under the Ancien Régime really was. The assembly put both France's financial and societal problems on full display for all the world to see and forced the king into convening an Estates-General, a slap in the face of the absolutist regime that had been the legacy of Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715), the Sun King. The meeting of the Estates-General in 1789 kicked off the French Revolution and served as the point of no return for Louis XVI's decaying monarchy.