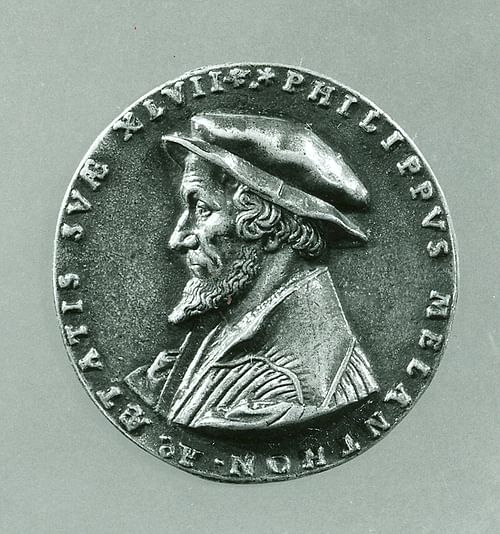

The Augsburg Confession is the affirmation of faith of the Lutheran Church written by Philip Melanchthon (l. 1497-1560) and presented at the Diet of Augsburg in June 1530. The document attempted to reconcile differences between the Lutherans and the Catholic Church in 28 articles: 21 stating tenets of Lutheran belief and 7 rejecting Catholic teachings.

Melanchthon was the friend and right-hand man of reformer Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) who had sparked the Protestant Reformation in 1517. Luther's 95 Theses, originally intended as an invitation to discuss abuses associated with the sale of indulgences, encouraged the widespread rejection of ecclesiastical authority in Germany and, once they were translated and published, in other regions. After his dramatic appearance at the Diet of Worms in 1521, Luther was branded an outlaw, but the belief system he had founded was reluctantly acknowledged by the Catholic hierarchy by 1530 since they had been unable to silence it.

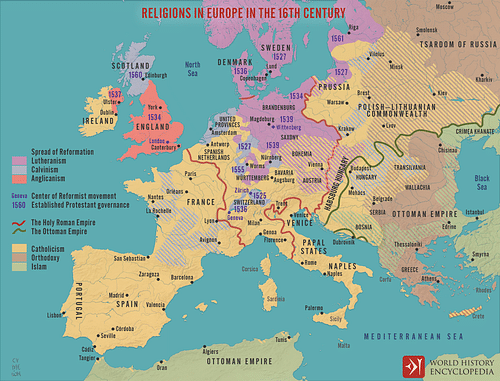

During this same period, c. 1521-1530, Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) had established the Reformation in Switzerland, causing further division, and in 1530, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1519-1556), called for an assembly at Augsburg to address the problem of Christian disunity as he feared an invasion of the region by the Ottoman Turks and needed his subjects united against them. Melanchthon wrote the Augsburg Confession (in Latin and German) to clarify Lutheran beliefs, including Luther's rejection of certain Catholic tenets, in terms acceptable to both parties.

The document was approved by the Protestant princes in attendance but rejected by Charles V and the Catholic Church through their Pontifical Confutation of the Augsburg Confession. Even so, the Confession and other documents relating to it became the central affirmation of the Lutheran movement, which was finally recognized as a legitimate religious entity at the Peace of Augsburg in 1555. The Augsburg Confession became a rallying point for the Lutheran princes of Germany, inspired the creation of other confessions of faith, and remains the affirmation of the Lutheran Church in the present.

Reformation, Division, & Diet of Augsburg

The Roman Catholic Church was the only Christian authority in Europe prior to the Protestant Reformation, and earlier attempts at reform had been silenced as quickly as possible. Luther was able to avoid this same fate through protection by powerful nobles, especially Frederick III (the Wise, l. 1463-1525) of Saxony, and his effective use of the printing press to disseminate his beliefs and criticisms of church policy. In Switzerland, Zwingli was able to accomplish the same thanks to support from the city council of Zürich and his own able manipulation of the press. The result was that, by 1530, there was no longer a single, unified Christian Church in Europe but, instead, fragmentary sects struggling to establish their own vision of Christianity.

Catholics continued to persecute members of these sects as heretics while the different sects argued amongst themselves. Zwingli's movement had encouraged the more radical Anabaptist sect, which he then condemned. The Anabaptists were then persecuted by both Protestants and Catholics even as those two parties fought with each other, sometimes in armed conflicts such as the Kappel Wars. The Lutheran sect also struggled to form a unified front as various members parted ways with Luther on the interpretation of scripture and liturgical practices.

Charles V, a Catholic, recognized that the situation had already gotten far out of hand and any hope of silencing the reformers had been lost. He set aside his personal feelings about the Protestants in the interests of the greater good of protecting his territory from an invasion by the Turks of the Ottoman Empire and so sent invitations across the land for an assembly of the Imperial Diet in Augsburg to be held in April 1530.

Luther and his colleagues were suspicious of these invitations, thinking Charles V was preparing some sort of trap, but they were encouraged to go by the Elector (a noble who elected the Holy Roman Emperor) John of Saxony, who believed the emperor's concerns over unity were legitimate and should be addressed. Luther, Melanchthon, and two other reformers, Johannes Bugenhagen (l. 1485-1558) and Justus Jonas (l. 1493-1555), met John of Saxony at Torgau where they wrote the first draft of the Confession (known as the Torgau Articles), and then the entourage continued to Coburg where Luther remained behind since, as an outlaw ever since the Diet of Worms, he could have been arrested in Augsburg.

Melanchthon revised the Torgau Articles on the journey south to Augsburg and sent a copy back to Luther, who approved of it, and then he revised the document further through input from Jonas and others. The delegation handed the Confession to Charles V on 25 June, and it was read aloud in German. Measures had been taken by Charles V and the Catholic delegation to limit the audience who might hear the document, moving the meeting from the large city hall to a small chapel. The Saxon Chancellor and Protestant lawyer Christian Beyer (l. 1482-1535), however, read loudly and enunciated clearly so that, the windows being open due to the hot weather, each word could be heard clearly by the crowd gathered outside.

Augsburg Confession & Others

The Confession began by addressing the Lutheran understanding of the nature of God, which Melanchthon had carefully drafted to be acceptable to the Catholic delegation and Charles V. He had prepared two documents, one in Latin and the other in German, since Charles V did not speak German. Melanchthon focused Article I of the Confession on similar beliefs held by the Lutherans and Catholics such as belief in the Nicene Creed, citing the Lutherans' same use of the term "Person" as the Church Fathers, and listing the same groups held as enemies of the faith by both parties. Article I states:

Our Churches, with common consent, do teach that the decree of the Council of Nicaea concerning the Unity of the Divine Essence and concerning the Three Persons, is true and to be believed without any doubting; that is to say, there is one Divine Essence which is called and which is God; eternal, without body, without parts, of infinite power, wisdom, and goodness, the Maker and Preserver of all things, visible and invisible; and yet there are three Persons, of the same essence and power, who are also coeternal, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. And the term "person" they use as the Fathers have used it, to signify, not a part or quality in another, but that which subsists of itself. They condemn all heresies which have sprung up against this article, as the Manichaeans, who assumed two principles, one Good and the other Evil; also the Valentinians, Arians, Eunomians, Mohammedans, and all such. They also condemn the Samosatenes, old and new, who, contending that there is but one Person, sophistically and impiously argue that the Word and the Holy Ghost are not distinct Persons, but that "Word" signifies a spoken word and "Spirit" signifies motion in created things.

The whole of the Augsburg Confession was written to address all aspects of the Lutheran faith and, Melanchthon hoped, to be acceptable to both Protestants and Catholics, even though it was already understood that Charles V and the Catholic delegation would almost surely reject it. The whole document is comprised of 28 articles, divided between 21 theses on Lutheran belief and 7 antitheses criticizing Catholic doctrine:

Art. I. Of God

Art. II. Of Original Sin

Art. III. Of the Son of God

Art. IV. Of Justification

Art. V. Of the Ministry

Art. VI. Of New Obedience

Art. VII. Of the Church

Art. VIII. What the Church Is

Art. IX. Of Baptism

Art. X. Of the Lord's Supper

Art. XI. Of Confession

Art. XII. Of Repentance

Art. XIII. Of the Use of the Sacraments

Art. XIV. Of Ecclesiastical Order

Art. XV. Of Ecclesiastical Usages

Art. XVI. Of Civil Affairs

Art. XVII. Of Christ's Return to Judgment

Art. XVIII. Of Free Will

Art. XIX. Of the Cause of Sin

Art. XX. Of Good Works

Art. XXI. Of the Worship of the Saints

Art. XXII. Of Both Kinds in the Sacrament

Art. XXIII. Of the Marriage of Priests

Art. XXIV. Of the Mass

Art. XXV. Of Confession

Art. XXVI. Of the Distinction of Meats

Art. XXVII. Of Monastic Vows

Art. XXVIII. Of Ecclesiastical Power

Article XXII began the criticisms and rejection of Catholic tenets, and Melanchthon added a concluding section in which he invited contribution and discussion of the articles, stating, "If there is anything that anyone might desire in this Confession, we are ready, God willing, to present ampler information according to the Scriptures." The German and Latin copies of the Confession were accepted by Charles V and the Diet after the document was read.

Other confessions were also brought before Charles V at Augsburg, the Tetrapolitan Confession (also known as the Strasbourg Confession), which sought to unite Lutheran and Zwinglian beliefs, written by the reformers Martin Bucer (l. 1491-1551) and Wolfgang Cupito (l. c. 1478-1541), and Zwingli's Confession to the Emperor Charles, written by Zwingli himself. Both of these were ignored by the Diet as they seem to have been considered poorer versions of Melanchthon's work and, in Zwingli's case, purposefully divisive. The Catholic priest and theologian Johann Eck (l. 1486-1543), who had debated Luther at Leipzig in 1519, wrote a refutation of Zwingli's Confession dismissing him as a threat to Christian unity who had already caused greater harm than the Turks or Huns. The Tetrapolitan ("four-city") Confession received no response at all.

Reaction of Luther & the Church

Luther, still at Coburg, became increasingly agitated at receiving no word from Melanchthon and the others prior to the presentation of the Confession, and when he finally did hear from them, he criticized Melanchthon for compromise. Scholar Lyndal Roper comments:

Luther was sent the confession only after it had been presented to the emperor and he complained that if he had written it, he would not have made so many concessions. He dashed off a letter that started by congratulating Melanchthon but then objected that he was going against Holy Scripture because Christ is the stone that the builders cast aside, that is, he should expect to be despised and cast aside. There was little else he [Luther] could do now. He saw himself as an unrecognized war hero. (321-322)

Charles V commissioned a refutation of the Augsburg Confession from the Catholic delegation, including Johann Eck, which was read to the Imperial Diet on 3 August but only to the secular attendees; the evangelical Protestants and especially Luther's delegation were not given a copy. As Roper notes, "The imperial side sought to prevent at all costs a theological dispute that Luther might win" (322). Afterwards, the two sides entered into negotiations to reach some mutual agreement and establish the unity Charles V had convened the assembly to accomplish. Melanchthon repeatedly wrote Luther for advice but received no answer. Roper elaborates:

[The delegation] needed urgently to know where they might compromise. Everything had been discussed in advance at the meeting of Luther and his companions at Torgau, Melanchthon conceded, but real-life encounters were always unpredictable. What was essential, and what could be negotiated? Luther, incensed by feeling that he had been ignored for several weeks, now took the opportunity to sulk. He sent word that he was furious with the Wittenberg delegation, but otherwise refused to respond. (322)

Melanchthon had incorporated Luther's suggestions on the Confession earlier but now was forced to revise and edit it on his own. Luther seems to have felt he was being sidelined in the movement he had established and led, and when he did finally respond to Melanchthon's letters, it was largely to criticize him for weakness in standing up for the faith. He encouraged Melanchthon to "remain firm, to be a man and act in a manly way" as Luther claimed he himself would do if he were at Augsburg (Roper, 327). Melanchthon was not only dealing with the negotiations and revisions of the Confession but also with stories of "signs and portents" which each side was interpreting as messages from God favoring their view and condemning their opponents.

Negotiations finally failed completely in September, and the emperor adjourned the Diet of Augsburg on the 23rd. Both sides had been willing to compromise to provide Charles V with the religious unity he had sought, but neither trusted the other to keep their word. Roper explains:

What finally kept the two sides apart was the absence of trust – on marriage, the sacraments, and other issues, the evangelicals simply did not believe that the Catholics meant what they said, or that they would keep their word. They feared that concessions would lead to their being crushed at a Church council that would be held outside Germany and set up to defeat them. The result was not inevitable, but rather a narrowly missed opportunity to prevent the splitting of the Catholic Church. This was why negotiations continued for so long, with one committee succeeding another, and why Charles had been willing to countenance ever more attempts to reach agreement. (330)

Roper, among other scholars, notes that, had negotiations been left entirely up to Melanchthon, an agreement might have been reached. Melanchthon, however, had to answer to Luther, who insisted there was no room for compromise and that Lutheran tenets, representing true Christianity, must triumph over the false teachings and policies of the Catholic Church. Melanchthon left Augsburg with the Confession having failed in his stated goal, and later stories of the 'rift' between Luther and Melanchthon – exaggerated as the years went on, and even up to the present day – date from this event.

Conclusion

The failed attempts at compromise and unity at Augsburg and the Protestant concern over an attack on German cities by Charles V and a Catholic coalition led to the establishment of the Schmalkaldic League in 1531 by the Lutheran princes. The league was a military alliance admitting any prince or polity who had signed or accepted the legitimacy of the Augsburg Confession. Membership included the understanding that armed forces would be provided, in the event of hostilities initiated by Charles V, to any in the league regardless of one's personal or political relationship with them.

The League helped establish Lutheranism throughout Germany while simultaneously dismantling Catholic establishments, confiscating lands owned by Catholic churches, monasteries, and convents, and providing the stability for the development of Luther's vision. Luther wrote his Smalcald Articles (in part), a more concise Lutheran confession than the Augsburg Confession, to assist the league in their goals. Luther's Preface to the Smalcald Articles exemplifies his view of the Catholic Church, and his refusal to compromise, as he accuses the pope of "lying and cheating," claims Catholics are "dreadfully afraid" of a free and open Christian council, and argues that the pope would prefer people be damned than admit any need for reform.

The Schmalkaldic League acted on Luther's condemnation of the Church and continued for 15 years while Charles V was busy fighting foreign wars, but in 1546, Charles turned his attention back to the Protestants of Germany and launched an offensive. The league had grown used to operating without opposition, and each prince regarded himself as superior to the others, and so when it came time to mobilize forces for military action, there was no unity of leadership and so no possibility of agreeing upon a cohesive strategy or tactics. Charles V won the Schmalkaldic War (1546-1547) not only through his own skill at seizing on opportunities but through the lack of trust and cooperation among the Protestant princes.

The Augsburg Confession, however, continued as the Lutherans' affirmation of faith, and, in spite of Charles V's efforts, Lutheranism had become so firmly entrenched throughout Europe that nothing could be done save to legitimize it at the Peace of Augsburg in 1555. The Augsburg Confession had influenced the others presented in 1530 and would continue to exert the same influence over later confessions. It is still recited in the present day by Lutherans as their official confession and echoes of Melanchthon's work can be heard in those of other Protestant sects around the world.