Aurelian was Roman emperor from 270 to 275 CE. He was one of the so-called Barracks Emperors, chosen by the Roman army during the turbulent period known as the Crisis of the Third Century (235-284 CE). Besides victories against various invading tribes, he successfully restored the Roman Empire by bringing the breakaway territories of the Gallic Empire and Palmyra back under Roman control, which earned him the title restitutor orbis ('Restorer of the World'). In order to defend Rome, he ordered the construction of the Aurelian Walls around the city, many parts of which are remarkably well-preserved thanks to their continued use as defensive structures well into the 19th century CE.

Rise to Power

Lucius Domitius Aurelianus was born on 9 September 214/215 CE in either Serdica or Sirmium in the province of Moesia (later Dacia Ripensis). We know little of his early life, except that he was of modest origins, his father being a colonus to a senator named Aurelius. He had a successful career during the reign of Gallienus (r. 253-268 CE), but despite a flourishing career under that emperor, Aurelian nevertheless was part of the conspiracy that eventually assassinated him. With the accession of the usurper Claudius II immediately thereafter, Aurelian was made commander (dux) of the cavalry. Despite successes against the various barbarian invaders such as the Goths, Vandals, and Juthungi on the Danube frontier, Claudius' reign was cut short when he succumbed to the plague which had broken out in 270 CE. Initially, Claudius' brother Quintillus succeeded as emperor, but he seems to have only reigned for a few months. Aurelian soon rose as a rival to Quintillus, and when the former was hailed emperor by the troops, he disposed of his rival (September or November 270 CE).

Early Reign

Once emperor, Aurelian immediately seized control of the imperial mint at Siscia (in modern Croatia), striking gold coins there in order to distribute as donatives to his soldiers and thus guarantee their loyalty. He then turned his attention to the wars with the Juthungi and the Vandals who had not yet been finished by Claudius II. With respect to the Juthungi, this tribe had successfully invaded Italy and, having plundered the north of it, were heading home with their booty, the weight of it making their return to their lands much slower. According to the fragments of the 3rd-century CE historian Dexippus, after Aurelian caught up with them, they promised him the contribution of 40,000 of their horsemen as well as 80,000 soldiers to serve in the Roman army. The emperor next turned his attention to the Vandals in Pannonia. After locating their main army, rather than directly attack them, Aurelian initiated a scorched earth policy around them, thus denying them access to food. This tactic worked, and the Vandals soon sued for peace, promising Aurelian the service of 2,000 of their cavalrymen before receiving food from the Romans so that they would not starve on their return home.

With these matters resolved and an ephemeral peace restored, Aurelian travelled to Rome. Upon arriving in the city, he had to address the immediate problem of a revolt in the city by the workers of the imperial mint. In the events leading up to this, it seems that the workers at the mint, in the emperor's absence, had developed an overconfident sense of independence that had crossed over the line to insubordination. Such behaviour led to corruption amongst the workers, who it seems were lining their pockets with imperial coin. What led to the revolt, however, is a subject of debate. It has been supposed that Aurelian's efforts to address the currency issue early in his reign may have made the mint workers uneasy; the prospect of an emperor known for instilling discipline and his possible curiosity at any illegal or corrupt activity may have moved the workers to revolt. Another possible cause for the revolt might have lain in the fact that its leader, the rationalis (chief fiscal officer) Felicissimus, may have been the tool of senatorial and equestrian interests who felt threatened by Aurelian's rule. In any case, the revolt lasted only a very short time before it was crushed by Aurelian, who then closed the Rome mint. Other domestic threats to Aurelian's rule included four separate attempts at usurpation by Septiminus (also called Septimius), Domitianus, Firmus (in Egypt during the Palmyrene war, although his existence is contested), and Urbanus, which were quickly found out and crushed.

While in Rome, Aurelian did his best to win the support of the people, cancelling debts to the treasury and making a public bonfire of the relevant records. This populist strain, according to the historian Ammianus Marcellinus, led him to descend on the rich 'like a torrent' and tax them punitively. The Senate was wary of the soldier-emperor but, realizing that little could be done to resist him, conferred its approval upon him.

Defending the Empire

In 271 CE, Aurelian found himself having to defend the empire from renewed incursions from the Juthungi, Alamanni, and Marcomanni. Aurelian found what are thought to be Juthungi and Alemannic invaders making incursions into Italy. After thinking he made peace with the Juthungi when meeting them at Milan in 271 CE, that tribe soon went back on their word and surprise attacked the Romans, inflicting a major defeat upon imperial forces. He defeated the invaders in three different places: at Fanum Fortunae, Metaurus, and Ticinus (near modern Pavia). This did not resolve the matter completely, as the invaders would simply regroup and then continue their attacks in other places. The best Aurelian could do was to anticipate enemy movements, find and defeat them in battle, and run the remainder to ground. Aurelian managed to do this and returned to Rome, possibly knowing that his victories had only provided a brief respite.

Upon returning to Rome Aurelian proclaimed a German victory but knew that this did not allay the fears of the city's inhabitants of a renewed barbarian attack. Meeting with the Roman Senate, the emperor proposed the construction of a wall around the city for its defence. Civilian workers were mobilized to perform this task, and a wall was built to defend the city, 6.5 m (21 ft) in height and just under 19 km (12 mi) in length. He followed this action with a march to the Balkans with his army, defeating Gothic forces in the area and killing Cannabaudes, their leader. Despite this victory, Aurelian realized that the province of Dacia across the Danube was too hard and too expensive to defend, and organized the evacuation of the province's inhabitants back across the river, resettling them in the new province of Dacia Aureliana, partly carved out of the old Moesian province.

Restorer of the World

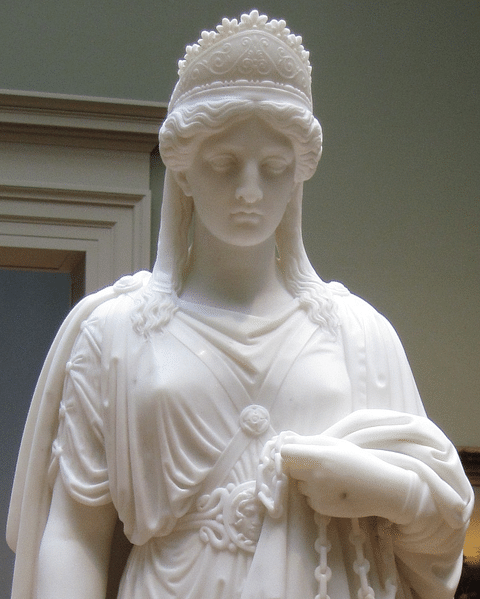

Aurelian's next move was against the breakaway empire of Palmyra that had wrested much of the empire's eastern possessions away from imperial control and into the hands of Palmyra's queen Zenobia and her underage son Vaballathus. Aurelian began his campaign against Palmyra in 272 CE, and marched through Asia Minor, reclaiming it for Rome and meeting with little resistance. When Aurelian offered mercy to resistant cities such as Tyana and took no reprisals against it once it was recaptured for Rome, word of this conciliatory policy spread to other cities, which opened their gates to Aurelian without any resistance whatsoever. Aurelian followed up these peaceful victories with military ones, defeating Zenobia's forces at the Battle of Immae and at Emesa. Within six months of the beginning of his campaign, Aurelian and his army stood at the gates of Palmyra, which surrendered. Zenobia tried to flee with her son to the Sassanian Persian Empire, but they were soon captured and made to walk the streets of Rome in the triumph that Aurelian eventually celebrated. Aurelian marched back westward, defeating the Carpi on the Danube. Palmyra tried to revolt shortly thereafter, which obliged Aurelian to return east and sack that city in 273 CE. Palmyra never regained the power or influence it previously enjoyed after this time.

After this, Aurelian turned his attention to the breakaway Gallic Empire in the West, which at this time controlled Gallic and British provinces. He defeated these rebels at the Battle of the Catalunian Fields (Châlons-sur-Marne), causing the Gallic emperor Tetricus to desert his own forces and sue for peace. Aurelian granted Tetricus mercy, and the erstwhile rebel marched with Zenobia in Aurelian's triumph which celebrated the reintegration of the Gallic and Palmyrene empires back into the Roman sphere of control. Aurelian proclaimed himself restitutor orbis ('Restorer of the World') to celebrate this occasion.

Aurelian is known for promoting the worship of Invictus Sol ('God of the Unconquered Sun'), creating an official priesthood as well as building a temple to that deity on the Campus Martius with this aim in mind. Although Aurelian did not aim to diminish the role of the traditional Roman state gods in enacting these measures, he hoped to use Invictus Sol as a way of making steps towards a degree of religious unity within the empire.

Death & Legacy

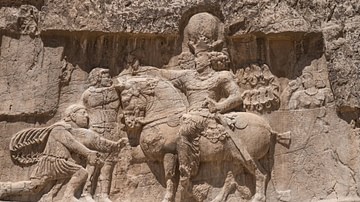

By 275 CE, Aurelian was planning a major campaign against the Sassanian Empire, perhaps taking advantage of the weak leadership that had come to the Persian throne after the death of Shapur I around 272 CE. Before, he could do this, however, he was assassinated in a household plot at Caenophrurium near the city of Byzantium.

Aurelian has almost universally been described as a ruthless emperor with a predisposition to cruelty (his nickname, manu ad ferrum "hand on hilt" implies that he may have solved problems with a sword rather than words). This portrayal, however, comes into conflict with the fact that he offered mercy on a number of occasions (to the city of Tyana, to Zenobia, to Tetricus) and might imply a bias against him by the historians who wrote about him.

Aurelian's death did much to eliminate existing threats, but it did not end the uncertainty that the empire would experience until 284 CE with the accession of Diocletian.