Review

| Rating: | |

|---|---|

| Title: | The World of Sugar: How the Sweet Stuff Transformed Our Politics, Health, and Environment over 2,000 Years |

| Author: | Bosma, Ulbe |

| Audience: | University |

| Difficulty: | Medium |

| Publisher: | Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press |

| Published: | 2023 |

| Pages: | 464 |

How sugar - which had been unknown for much of human history - became a pervasive element in our lives only in recent times is the subject matter of Ulbe Bosma’s magisterial work "The World of Sugar." The rise of sugar from relative obscurity, the author argues, has been achieved at the expense of slavery, environmental degradation, and human well-being. Extensively researched, this work should be an engaging read for both scholars and general readers.

While granulated sugar was produced in India as early as the 6th century BCE, its usage for a long time remained limited to royalty or ceremonial purposes. It was not until the 13th century that sugar became a major commercial product throughout Eurasia. India, China, Persia, and Egypt were significant in this transformation, prompting Bosma to state that “sugar capitalism began in Asia.”

The introduction of sugarcane to the Iberian Peninsula and Sicily by the Moors eventually shifted Europe’s reliance on Asian-based sugar. By the 15th century, Valencia, Granada, Sicily, and Cyprus became key sugar suppliers, as well as the newly Portuguese-acquired Madeira and the Azores.

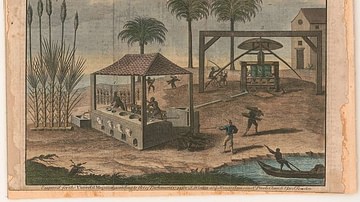

It was Columbus’ introduction of sugarcane to Santo Domingo on his second voyage in 1493 that set the stage for industrial-scale production of sugar. In 1500, the Spanish began commercial sugar production in Hispaniola as did the Portuguese shortly after in Brazil. The Dutch, the French, and the English followed suit. Sugar became an integral part of European colonialism.

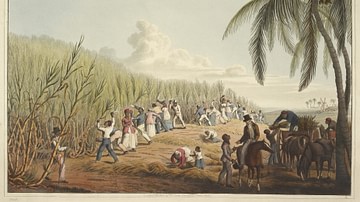

To harness the Americas’ immense sugar-making potential, European planters resorted to importing African slaves to work in the plantations. An estimated six to nine million slaves were imported from Africa to work in sugarcane fields under brutal conditions. Nearly 40% of the enslaved Africans died within the first year. By the mid-19th century, half of the sugar consumed by the working class in Europe and North America was produced by "enslaved people," writes Bosma.

Bosma documents how slave workers in Haiti were able to revolt against their cruel French masters and eventually gain their freedom. The author could have mentioned that the French exacted a huge price for Haiti’s independence by forcing it to pay reparations to the descendants of their masters for generations.

A major strength of Bosma’s analysis is how sugar capitalism was a product of the intertwined economic interests of the planters and the home country’s ruling class. Citing the English plantation in the Caribbean, Bosma informs us that as many as seventy-five members of the British Parliament directly owned plantations that used slavery or invested in trades that relied on slavery.

The support of their national governments also enabled planters to develop remarkable ingenuity during difficult times. When Napoleon’s continental blockade prohibited the import of sugar from the British colonies, the continental planters quickly developed beet sugar aided by tariffs. Likewise, after slavery was universally abolished, the sugar industry found alternatives in indentured labor from India, China, and Southeast Asia and forced cultivation in Java. In Louisiana, planters enticed approximately 300,000 Sicilians over several decades to primarily work in the sugar fields.

To protect the sugar industry, the U.S. today subsidizes it to the tune of $ 4 billion a year. This has helped keep sugar prices low, enabling beverage companies to mass market sugary drinks globally alongside health implications like diabetes, cancer, and other diseases. North Americans currently consume a staggering 60 kilograms (132 lbs.) of sugar per person annually.

Bosma, a renowned professor of international comparative social history, has put together an impressive work drawing on his expertise and a vast array of research. A work on this global scale deserves a bibliography. A glossary would have helped readers to grapple with terms such as "vacuum pans" and "sugar central." In his conclusion, Bosma hopes that legislative bodies can limit individual sugar consumption to the WHO-prescribed average of 20 kilograms (44 lbs.) per year. Unfortunately, as long as policymakers depend on political contributions for their viability, any change is unlikely to happen in the foreseeable future.

About the Reviewer

Cite This Work

APA Style

Chaudhuri, S. (2023, September 06). The World of Sugar: How the Sweet Stuff Transformed Our Politics, Health, and Environment over 2,000 Years. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/review/381/the-world-of-sugar-how-the-sweet-stuff-transformed/

Chicago Style

Chaudhuri, Shankar. "The World of Sugar: How the Sweet Stuff Transformed Our Politics, Health, and Environment over 2,000 Years." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified September 06, 2023. https://www.worldhistory.org/review/381/the-world-of-sugar-how-the-sweet-stuff-transformed/.

MLA Style

Chaudhuri, Shankar. "The World of Sugar: How the Sweet Stuff Transformed Our Politics, Health, and Environment over 2,000 Years." World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 06 Sep 2023. Web. 11 Dec 2023.