Without the valuable contributions of historians, later generations would have little knowledge of the past - the good as well as the bad. Herodotus and Thucydides, the fathers of historical writing, would never have written their histories. Without Plutarch one would know nothing of the lives and accomplishments of many of the great Greeks and Romans. Lost would be the contributions of great civilizations - the Sumerians, the Egyptians, and the Persians. Without Arrian or Diodorus, how would anyone know of the military campaigns of Alexander the Great? And, lastly, without Titus Livius, better known as Livy (59 BCE - 17 CE), the struggles of the Roman people and the creation of an empire would have been forgotten long ago.

While he would spend most of his adult life in Rome, arriving there at the age of thirty, Livy, was actually born in the small town of Patuvium located in northern Italy, modern day Padua, around 59 BCE, and it was in his place of birth that he would return to die in 17 CE at the age of sixty. Although much of his early life is shrouded in mystery, it was in this small town that he received his formal education at the time of the civil wars of 49 to 30 BCE. It was in his youth that he first wrote short historical and philosophical works. Little of his family is known; he was married and had a least one son and a daughter who would later marry a rhetorician named Lucius Magus. While there is only speculation as to why he travelled to Rome, it was there that he would achieve fame and even notoriety following the publication of a 142 volume history of Rome entitled Ab Urbe Condita or From the Foundation of the City. It was a complete history of the Roman Republic from it early founding at the time of Aeneas to the end of the Republic and through the early years of Imperial Rome and the reign of Emperor Augustus - a period of over seven centuries.

Unlike many historians of the era, Livy never held a public office and had no political or military experience (something for which others, including his contemporaries, considered a fault) and unlike many in his profession, he would assume the role of a full-time historian. The multi-volume work of which only a small portion has survived (volumes 1 to 10 and 21 to 45) would consume him, yet his surviving work offers an amazing insight to both the growth of the Roman Republic and what he viewed as the demise of the Roman character. These volumes (the last twenty-two volumes were not published until after his death) were written in a year-to-year structure, a pentad, and demonstrate what one historian saw as a more Stoic perspective, but one that emphasized ethics, not the fatalism of classical Stoicism. While he lacked personal insight into the mind of a soldier, his works demonstrated respect for the heroism seen in Roman victories. Livy believed that the historical environment surrounding Rome shaped its people. To him history should not just inform the reader but elevate him as well - what some saw as moral education.

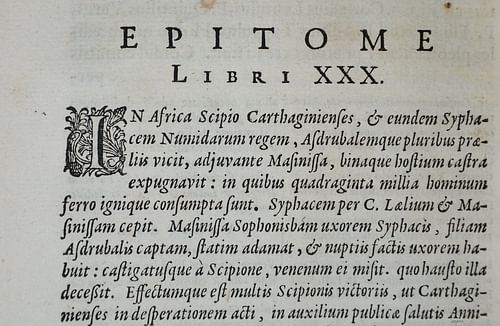

While the majority of his work is lost, there remain brief summaries or periochae of all but two books. The first volume which covered the longest time period (over 200 years) began with the arrival of the Trojans in Italy and ended with the expulsion of King Tarquin and the Etruscans around 509 BCE. In the preface to this book he laid the foundation for his history. He wrote in an almost apologetic manner:

Whether the task I have undertaken of writing a complete history of the Roman people from the very commencement of its existence will reward me for the labour spent on it, I neither know for certain, nor if I did know would I venture to say. For I see that this is an old-established and a common practice, each fresh writer being invariably persuaded that he will either attain greater certainty in the materials of his narrative, or surpass the rudeness of antiquity in the excellence of his style.

He took pride in his role of writing the history of what he called “the annals of the foremost nation in the world.” He understood the troubles that beset Rome in the years prior to Augustus' reign. He said he had to close his eyes:

to the evils which our generation has witnessed for so many years, so long, at least, as I am devoting my thoughts to retracing those pristine records, free from all the anxiety which can disturb the historian of his own times even if it cannot warp him from the truth.

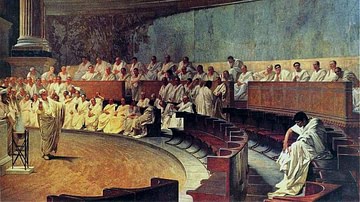

The subsequent books, those up to number 45, trace Rome from the days of the creation of the Twelve Tables through the Punic and Macedonian Wars. In fact, most of what is known about these wars is due primarily to Livy's work. The opening paragraphs of the second book speak of the overthrow of the last king and establish another reason for writing his history:

It is of a Rome henceforth free that I am to write the history - her civil administration and the conduct of her wars, her annually elected magistrates, the authority of her laws supreme over all her citizens. The tyranny of the last king made this liberty all the more welcome, for such had been the rule of the former kings that they might not undeservedly be counted as founders of parts, at all events, of the city….

Unfortunately, many of those historians who followed him criticized him for not being an original researcher and called him careless for not verifying many of his facts. While he used several of the sources available at the time, he was dismissed as being merely a writer and not a true academic. He had a poor knowledge of geography (as many other writers did) and had difficulty with Greek but, to his credit, he was a master of drama.

To others Livy's major rationale for writing his history was to illustrate the evolution of the Roman character - the conditions that developed or shaped the virtues that made his fellow Romans great; critics believe that Livy exaggerated many of these intrinsic values. Although Livy was skeptical about the old Roman gods who continually meddled in human life, he acknowledged the value of Roman religion and its traditional rituals. He saw how the neglect of this important institution led to the eventual decline of Roman morality. Unfortunately, Livy was obliged to not only discuss the rise of these values but also their deterioration.

While his treatment of the Emperor Augustus was thought to be very kind, controversy still surrounds Livy's relationship to him. Although most concur that they could be considered friends, this can only be speculative since the books covering the emperor's reign are lost. It is known from other sources that Augustus called Livy Pompeian in reference to his admiration of the old Republic - Livy thought the Roman senator Cicero represented the best of republican principles. However, Livy's independent nature prevented him from ever being regarded as a court historian. While Augustus favored him, Caligula disliked him and thought his writing sloppy, but, supposedly, Livy had a tremendous influence on the future Emperor Claudius, enabling him to write his own histories.

Over the years, historians who followed Livy have criticized his work for one reason or another. One can only speculate what the missing books would add to our historical knowledge. To some his history is confusing, demonstrating a Rome that waged constant warfare - Carthage and Macedonia for example - and was constantly besieged by internal dissension. As one historian put it, to Livy it was a Rome created by divine favor gained through piety and morality, but when this was lost, it could only spell disaster.