In 509 BCE with the exit of the last Etruscan king, Tarquin the Elder, the Roman people were presented with a unique opportunity, an opportunity that would eventually have an immense impact on the rest of Europe for centuries to come: the chance to create a new government, a republic. Although most rights were restricted to an elite patrician class, this new government would have three-branches: a centuriate assembly, a Senate (whose only purpose was to serve in an advisory capacity), and two co-executives, called Consuls. The idea of co-consuls meant no one individual could abuse the executive power. A consul, elected through the assembly, had the power of a king, power albeit restricted by his one-year term and the authority of the other consul. Although not a true democracy by the modern definition, the Roman Republic appeared somewhat representative.

Elected by the assembly in a special election, each consul, who had to be at least 42 years old and initially only a patrician, served a one-year term and could not serve successive terms. Basically, a consul served as both a civil and military magistrate with almost unlimited executive power, or imperium. In the city of Rome he exercised imperium domi, the power of enforcing order and obedience to his commands, but this power was not absolute. An individual had the right to provocatio ad populum, an appeal of the decision of the consul. Usually, this appeal only occurred if it was a matter of life, death, or the individual believed he was being singled out by the consul. However, outside the city, the consul had unrestricted power in the field, or imperium militiae, a power often extended to a commander, enabling him to use whatever force he considered necessary.

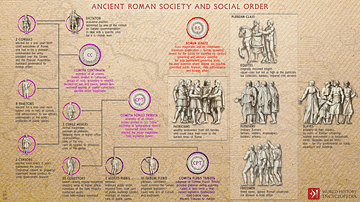

At the time of the Etruscans, there were two distinct classes of people within the city of Rome: the aristocratic families or patricians, who owned most of the land; and the plebians, who comprised the remainder of the populace. Despite the fact that not all plebians were poor, they were excluded by law from participating in the government; no voting rights meant no membership in either the assembly or Senate. Over time as the city grew and Rome began to extend its borders, the plebians tired of being considered second-class, rebelled, and went on strike, protesting their restriction from participating in their government; this was called the First Secession of the Plebs. The patricians had little choice but to make certain compromises. The plebians were permitted to create their own assembly called the Concilium Plebis or Council of Plebs. The Council of Plebs named their own magistrates called tribunes and had the power to make laws affecting the plebians.

Realizing the need for the cooperation of the plebians, the patricians gradually recognized their rights in what became known as the Struggle or Conflict of the Orders. However, without any law code in place, the plebians feared possible abuses, so a new series of laws, the Twelve Tables, was enacted in 450 BCE. As time passed, the lines between the two classes gradually lessened (although never completely disappeared). In 367 BCE a new law was passed allowing a plebian to be elected consul, and in 366 BCE the first plebian consul was named. Later, by law, at least one of the consuls had to be a plebian. In 287 BCE the Lex Hortensia was passed, making all laws enacted by the plebian assembly binding to all citizens.

Whether it was a plebian or patrician, a consul's powers remained the same: he presided over the Senate, proposed laws, and commanded the army. If a consul died or resigned, the other consul would hold a special election and that individual would serve the remainder of the term. A list of consuls and an official chronicle of each term in office was also kept, called the fasti. Even the Roman calendar was dated by the name of the consul in power. The position of consul was often the highpoint of a Roman politician's career. After he left office, he remained a member of the Senate and would most often be rewarded for his service and named governor of one of the Roman provinces, a pro-consul.

Bedecked in his light woolen toga with a purple border (an indication of his rank), a consul was always accompanied by twelve attendants who carried the symbol of his power, the fasces, and cleared a path for him as he walked the streets of Rome. Gradually, many of the consul's powers were given to other offices, called the cursus honorum; the censor was responsible for the census, the praetor (the only other magistrate with imperium powers) dealt with dispensing justice in both Rome and the provinces, the quaestor managed financial affairs, and the aedile supervised public games, the city's water supply, and the Roman roads. Often, each of these offices served as a path to the consulship.

Unfortunately, the demise of the Republic and rise of the empire under Augustus would spell the end of power of the consul. The assemblies would lose their ability to make laws and thereby name a consul. While the title of consul would remain, an emperor would simply assume the title himself. This passing does not diminish the role of the consul during the Republic. Rome was able to make the successful transition from a king to a magistrate - the consul - who was imbued with much of the same authority. The government that ruled Rome through its early years of empire building would serve as a role model for governments yet unborn.