Warfare is generally understood to be the controlled and systematic waging of armed conflict between sovereign nations or states, using military might and strategy, until one opponent is defeated on the field or sues for peace in the face of inevitable destruction and greater loss of human life. The first recorded war in history is that between Sumer and Elam in Mesopotamia in 2700 BCE in which Sumer was victorious, and the first peace treaty ever signed ending hostilities between nations was between Rameses II (the Great) of the Empire of Egypt and Hattusili III of the Hittite Empire in 1258 BCE.

In both of these cases, war was waged, and a treaty signed, to resolve political and cultural conflicts. Warfare has been a part of the human condition throughout recorded history and invariably results from the tribe mentality inherent in human communities and their fear or mistrust of another, different, `tribe' as manifested in the people of another region, culture, or religion.

Warfare & the Unification of China

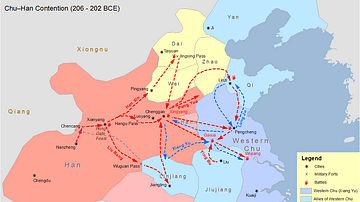

One example of the tribe mentality resulting in warfare can be seen in China during the Warring States Period (476-221 BCE) where seven tribal states fought for supreme control of the land. The Zhou Dynasty (1046-226 BCE) which had served as the seat of political authority in China (though not of a unified China) was in decline and each of the independent states recognized the opportunity to gain supremacy.

As every state employed the same tactics and observed the same policies of war, none could gain a significant advantage over the others. The Chinese historian Sima Qian wrote that the people of China during this period knew no other life than that of warfare generation after generation.

The first military conflicts in China are recorded with the rise of the Xia Dynasty (c.2070-1600 BCE) but, once political contentions were settled, peace prevailed. During the Warring States Period, however, the country was in constant turmoil. This situation was resolved by the King of Qin, Ying Zheng, who implemented the concept of Total War in his campaigns so effectively that, between 230-221 BCE, he had conquered the other states completely.

Ying Zheng unified China under the Qin Dynasty and claimed for himself the title of First Emperor or, Qin Shi Huangti, the title by which he is best known. His use of warfare to resolve long-standing political disputes serves as a paradigm for the use of war generally, whether on a larger or a smaller scale.

The Victors & the Vanquished

Warfare in ancient times was conducted differently than what would be considered acceptable by today's standards; the vanquished could be certain that slavery or summary execution awaited them. When Alexander the Great took the Phoenician city of Tyre in July of 332 BCE, he had most of the population killed and sold the rest into slavery. In September of 52 BCE, when Julius Caesar defeated Vercingetorix and his Gallic tribes at Alesia, the garrison was sold into slavery and each man in Caesar's legions received, as a gift, one Gaul as a personal slave. Over 40,000 Gauls were taken as slaves by the legionnaires alone, not counting those others sold to tribes who made peace with Caesar and formed alliances after Alesia.

When Octavian defeated Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE a similar fate awaited the conquered who were not fortunate enough to die in battle. This same model of warfare obtains as far back as Sargon the Great of Akkad (2334-2279 BCE) who united Mesopotamia under the Akkadian Empire and was perfected by the Assyrian Empire during the Iron Age (1000-500 BCE). The Assyrians were the first political force to employ large-scale deportations of the conquered populace to other regions and a re-settlement of the region by their own people. The citizens of the defeated city or state were either sold into slavery or forced to re-locate to an area or region dictated by their conquerors.

Tactics & Formations

The armies who waged war on the field were initially made up of infantry units who engaged an enemy force and closed with them using spears, shields, and some form of body armor and helmet. In time, armies developed to include shock troops (infantry who engaged the opposing lines in tight formation) and peltasts (infantry in looser formations who fired long range missles at the enemy and were more mobile). The formation known as the phalanx was the standard in virtually every army from its origin in Sumer in 3000 BCE through the time of the Roman Empire. The phalanx was modified many times through initiatives by men such as Philip II of Macedon or his son Alexander the Great but the basic formation, and its effectiveness, remained constant.

With the introduction of the horse to combat, cavalry units arose and the war chariot was frequently employed in battle. As armies grew in size, and as history established the precedent of empires, more and more resources were brought to bear in battle including the use of animals such as camels (which Cyrus the Great employed brilliantly at the Battle of Thymbra in 546 BCE) or elephants (famously used by Hannibal in the Second Punic War 218-201 BCE) or even cats, which were used by Cambyses II of Persia to defeat Egypt at the Battle of Pelusium in 525 BCE.

The Persian king was aware of the Egyptian veneration of cats and so had his army paint the image of the cat on their shields and, further, drove cats and other animals sacred to the Eyptians before the front lines. The Egyptians, unwilling to risk the wrath of their gods should they injure any of the animals, surrendered to the Persian army.

The first naval battle in recorded history was fought between the ships of the Hittite King Suppiluliuma II and an invading fleet from the island of Cyprus in c. 1210 BCE. Ships were no doubt used in battle before this date, however, and records indicate that Sargon of Akkad made use of boats in warfare which could be dismantled and carried over land.

The peltast units with their ability to inflict severe damage on an enemy long-range eventually inspired the artillery unit who used large weapons for the same purpose. Examples of artillery from the Roman Army are the Scorpio (a large crossbow), the Ballista (similar to a catapult), the Onager (a small Ballista), and the Catapult. By the time the Roman army was conquering the world, all tactics and every resource available in the service of warfare was made use of by the legions.

Ancient Armies & Weaponry

Battle strategies and and methods of warfare differed by country, by ruler and by era. In ancient Egypt the army was equipped with a simple spear and a leather shield but, by c. 1570 BCE, when the Egyptians defeated the foreign Hyksos who had taken Lower Egypt, they artfully employed the horse and chariot, body armor, and the composite bow as well as the bronze Khepesh sword.

Ironically, it was the Hyksos themselves who had given the Egyptians the technology (especially the composite bow, the tin bronze sword, and chariot) to defeat them. Prior to the arrival of the Hyksos in Egypt, the army was largely equipped with the same kinds of weapons they had used in the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE). Advances in weaponry, due at first to the Hyksos and then to the Hittites, led to the development of the professional fighting force of the New Kingdom (c. 1570k-1069 BCE) which created and maintained the Egyptian Empire.

The Persian Empire favored armored cavalry, heavy infantry (of whom the elite were known as the 10,000 Immortals) and archers who would rain down arrows on an opposing force to create 'awe and wonder' in the ranks. The ancient Greeks relied on armored infantry (the Hoplites) and the phalanx formation, a dense grouping of soldiers with long spears and interlocking shields. In Greece the infantry did most of the fighting, no matter what city-states were involved, the notable exception being the naval battle of Salamis in 480 BCE.

Philip II of Macedon introduced the sarissa (a long spear) to the phalanx which greatly enhanced the formation's effectiveness on the field, and Philip's son, Alexander the Great, made use of the sarissa in his infantry phalanxes in his own campaigns but also employed light and heavy cavalry and chariots to effect. The three-line legion of the Roman Empire, equipped with body armor, spear, shield and short sword replaced the phalanx formation and, supported by cavalry, proved itself the greatest fighting force in antiquity after Alexander the Great.

Every ancient culture, more or less, followed the same basic pattern of developing rudimentary weapons (usually based on tools they had used in hunting) which then were improved upon as members of different tribes came in contact - and conflict - with each other. As tribes became cultures and civilizations with differing interests, conflict became more common and weaponry, and warfare, more sophisticated in an effort to achieve greater results with less effort. No matter the culture or the time period, governments have routinely shown more interest, and exerted more effort, in warfare than in almost any other aspect of a nation's life.