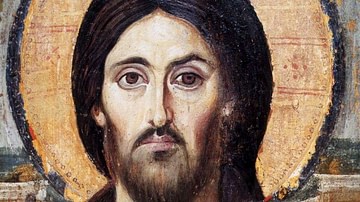

The New Testament contains four gospels attributed to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. The four gospels are not biographies of Jesus, nor are they history as we define it. What each gospel attempted to do was write a theological explanation for the events in the life of Jesus of Nazareth. By narrating his life, his ministry, and his death, The Gospels argued that these events should be interpreted in relation to the history of Israel.

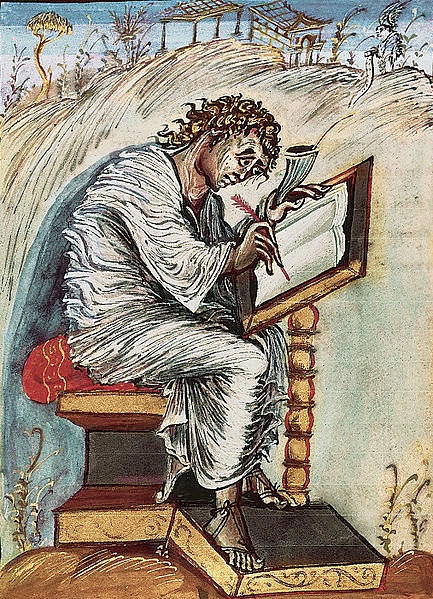

The word 'gospel' derives from the Anglo-Saxon for 'good news', and the writers are deemed 'evangelists' from the Greek euangelistes (bringer of good news). In this context, the 'good news' is the message of the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth that the kingdom of God foretold by the prophets of Israel was imminent.

The gospels were produced from c. 70 CE to perhaps 100 CE. Their portraits of Jesus, who he was, and why he was here, differ in relation to both later reflections and changes in the demographics of the earliest Christian communities over time. The four gospels vary in some of the details of Jesus. The two nativity stories of Matthew and Luke are thrown together under the Christmas tree, although they differ in many ways. (Matthew has the star and the Magi; Luke has the stable and the shepherds.) However, when the gospels agree on details, this does not indicate four different sources. Mark, being first, was used and edited by the other three.

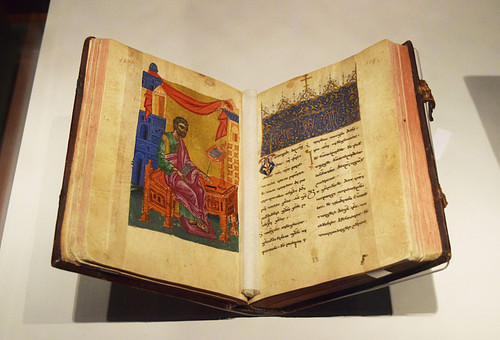

Authorship

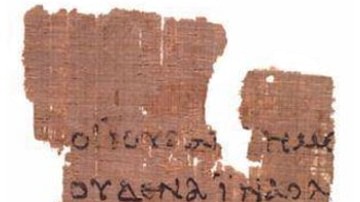

The original texts of the gospels had existed for about a hundred years with no names. The Church Fathers in the 2nd century CE assigned the names; none of the writers signed their work. The gospels are not eyewitness accounts; none of the gospel writers ever directly claimed to be an eyewitness. One exception is Luke, who says he interviewed witnesses but gives no further details. In their attempt to provide backgrounds for the writers the Church Fathers tried to align them as close to the original circle of Jesus as possible. They were also aware of a fundamental problem; the first disciples of Jesus were fishermen from Galilee who could not read and write the level of Greek in these documents.

In the Acts of the Apostles, Luke wrote that Peter had a disciple named John Mark who accompanied Peter in his travels. By the 2nd century CE, the legend that Peter had died in Rome under Roman emperor Nero (r. 54-68 CE) emerged and so the Church Fathers claimed Peter dictated this gospel to Mark in Rome. In Mark and Luke, when Jesus called the tax-collector to follow him, that individual is named Levi. In Matthew’s gospel, he is named Matthew. The Church Fathers identified this writer by this clue, thus the name. It was believed that there had been an earlier form of Matthew's gospel in Hebrew. This gave it more credible historical roots and so they placed it first in the New Testament.

The Church Fathers knew that the third gospel and the Acts of the Apostles were written by the same individual, but there was no Luke in the list of disciples. However, the second half of Acts relates the missionary journeys of Paul. In one of Paul’s letters, he mentioned a traveling companion named Luke. For the Fathers, this was eyewitness testimony to the missions. The fourth gospel, John consistently refers to a character by the name of "the beloved disciple". The Church Fathers knew of someone named John the Elder in Ephesus who was supposedly an original disciple and so assigned this gospel to him and claimed that he was John, the brother of James (the sons of Zebedee).

The Relationship Among the Gospels

The way in which the gospels relate to each other is known as the Synoptic Problem. 'Synoptic' (Greek: 'seen together') is the term for Mark, Matthew, and Luke. All three have the same structure and similar stories. The 'problem' was analyzing their order and the ways in which they edited each other.

Although second in the New Testament, Mark is the earliest gospel, written c. 69/70 CE during the Jewish Revolt against Rome. Almost all of Mark appears in Matthew and Luke. Those portions are verbatim in both texts. This is rare in translations and so scholars are convinced that Matthew and Luke had a written copy of Mark before them. In addition to Mark, Matthew and Luke have additional teachings, which also appear verbatim. No source for this has survived, but scholars attribute this to a "Q source" (from Quelle, 'source' in German). Matthew and Luke each contain unique material, labelled as M and L, respectively, as seen in the schematic below.

| Mark | Matthew | Luke | John |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Mark, Q, M | Mark, Q, L | Mark? Matthew/Luke? |

| Tradition? | John's unique concepts |

We have yet to discover any written sources for Mark. Our earliest texts, Paul’s letters (c. 50s and 60s CE), contain mostly concepts of the resurrected Christ, Paul’s vision. Paul did know that Jesus taught against divorce, and his last supper formula is very close to Mark’s. The letters lack reference to the parables, the miracles, and the details of the trial(s) of Jesus, but he does refer to the crucifixion. The assumption is that Mark utilized oral traditions. It is difficult to know whether Jesus really said what Mark attributed to him, however, by analyzing the historical context, whether a saying reflects conditions in Judea in the 20s and 30s CE (the timeframe of their story) or issues in the first communities of 50s - 100 CE, Mark is now recognized as a major contributor to this gospel.

Dates & Provenances for the Gospels

The gospels do not have internal dates to locate when they were written. Mark does, however, frame his story in relation to the Jewish Revolt and the destruction of the temple. In his sequel, the Acts of the Apostles, Luke mentioned Porcius Festus who ruled Judea in 62 CE and so it had to be written after that date. We also do not know where these gospels were written. From overall clues in the texts and information about locations and cities in the 1st century CE, scholars have put together a probable schematic:

| Mark | Matthew | Luke-Acts | John |

|---|---|---|---|

| 69/70 CE | 85 CE | 95 CE | 100 CE |

| Rome? | Galilee | Rome? Antioch? | Ephesus? |

The Methods & Problems of the Gospel Writers

The followers of Jesus (like Jesus himself) were Jews. “Christianity” as an independent religion did not exist in the 1st century CE. This period of Jewish history was characterized by the formation of different Jewish sects. They agreed on the basics such as Abraham and the Law of Moses, but they disagreed over how to maintain a distinct Jewish identity in the new cosmopolitan world of the Roman Empire. The followers of Jesus became one of these sects, although we refer to them as Christians for convenience, and by the time Mark wrote (c. 70 CE), Gentiles (non-Jews) may have outnumbered Jewish believers.

The one fact concerning Jesus of Nazareth that all scholars agree upon is the manner of his death. Without being able to absolutely claim which traditions about this event are historical, we accept the crucifixion because it was a problem for the earliest believers. Paul acknowledged this "scandal of the cross" as a "stumbling block" for both Jews and Gentiles (1 Corinthians 1:23) because crucifixion was the Roman punishment for treason. As the tradition of how he died was attested very early, the gospel writers had to explain and rationalize it. Another problem was the perception that Jesus was a failed prophet. Despite his urgings that the kingdom of God was imminent, it had not come by the end of the 1st century CE.

Jewish sects had a basic method when they constructed their arguments. They turned to the Jewish Scriptures and the Law of Moses and re-interpreted the texts to validate their arguments. Like their Jewish brothers, the writers of the gospels also turned to the Scriptures. A new interpretation of the Scriptures validated their claims that, despite appearances to the contrary, Jesus did fulfill what the prophets had foretold concerning the end times. Quotes and allusions to the Scriptures abound in the gospels.

In Isaiah, chapters 49-53 are known as "the suffering servant" passages referring to a "servant of God", a "righteous servant" who underwent suffering, torture, and death for his faithfulness. God raised him from the dead and placed him next to him on his throne. The followers of Jesus now claimed that Isaiah was predicting the events in the life of Jesus. Mark alluded to these passages in his description of the crucifixion: "He went as a lamb to the slaughter," "He was pierced for our transgressions." The "suffering servant" died for the "sins of the nation". This is the way in which the death of Jesus was explained.

The Christian claim that Jesus was resurrected was followed by the claim that he had been exalted to heaven. There were precedents for this in Second Temple Judaism. By the 1st century CE, there were stories that many of the patriarchs (Noah, Abraham, Jacob, Moses) were in heaven along with the Maccabee martyrs. Where Christians differed was placing Jesus above all others on the throne of God.

Jews & Gentiles

The disciples of Jesus took his message to the synagogues throughout the Eastern Empire. To their surprise they encountered Gentiles (non-Jews) who wanted to join. The Acts of the Apostles and Paul in his letter to the Galatians, related a meeting that was held in Jerusalem (c. 49? CE) to decide what to do with this new group. Some believed that these Gentiles had to fully convert to Judaism, meaning circumcision, dietary laws, and Sabbath observance. This group is designated as Jewish-Christians. Others argued that they did not have to convert first, championing the inclusion of Gentile-Christians. Led by James (Jesus’ brother), it was decided that the Gentiles did not have to fully convert, but they did have to cease all idolatry to the other gods.

Even though a decision was taken at this Council, apparently the debates continued; it is the dominating topic of Paul’s letters. The inclusion of Gentiles is validated by relating Jesus’ encounters with them; Jesus himself approved the Gentile mission. For example, in the story of the Syrophoenician woman in Mark 7:24-30, a Gentile woman had greater faith than the Jews.

Mark also had to convince the Roman authorities that his Jews were not in league with the rebels of the Jewish Revolt against the Roman Empire. All four gospels put the blame for Jesus’s death on the Jews and whitewashed Pontius Pilate who proclaimed Jesus innocent in relation to treason. According to the gospels, despite the crucifixion, Jesus died over religious disagreements with the Jewish authorities, and by implication, his followers were innocent of the treason charge as well.

The Kingdom of God

When the disciples in Mark asked Jesus when the kingdom would get here, he said, "Truly I tell you, some who are standing here will not taste death before they see that the kingdom of God has come with power" (Mark 9:1). Mark, ignoring the 40 years between the death of Jesus and the recent war, saw the destruction of the Temple as a sign of the end. For Mark, as well as Paul, the kingdom would come in their generation.

But an earlier Christian solved the problem, fully articulated by Paul. This was the concept of the parousia, the second appearance. When Jesus was here, he fulfilled some of the events of the kingdom. Now in heaven, he was coming back. Until then, Christians should live proleptically, as if the kingdom was already present in their communities. When Jesus came back, there would be a final battle and a final judgment.

The Four Portraits of Jesus

All four gospels presented Jesus within the frame of their own experience. Scholars focus on their distinctness and try to reconstruct what was happening in their communities at the time of their composition.

Mark: The Apocalyptic Jesus

Mark’s conviction that end times were beginning colors the ministry. Everything Jesus did was understood within the frame of apocalyptic ideas. We use the term 'apocalyptic' as ideas shared by many Jewish groups, awaiting God’s final deliverance. This is particularly highlighted in Mark, where he presented the ministry as a battle between Satan and Jesus. By the 1st century CE, the idea that Satan now ruled this world is played out in the many exorcisms (the driving out of demons) in Mark.

Mark’s favorite title for Jesus is "the son of man." Detailed in various apocalyptic texts at the time, this figure was a pre-existent entity created by God to be the final judge of all the nations. Thus Jesus had the power to forgive sins.

Matthew: The New Moses

When Moses gave his farewell speech to the Israelites in Deuteronomy (18:15), he said: "The LORD your God will raise up for you a prophet like me from among you, from your fellow Israelites. You must listen to him." Matthew structured his entire gospel around the claim that Jesus was the new Moses. His nativity story includes numerous references to the story of Moses and the Israelites in Egypt. Herod the Great in this story plays the part of Pharaoh.

Matthew premiered his main arguments in the Sermon on the Mount. Contrary to popular belief, the sermon was not a rejection of the Law of Moses; Matthew intensified it. "But I tell you that anyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart." (5:28). This was the model for the ideal community until Jesus returned. The passage ends with: "Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect" (Matthew 5:48).

The vitriol against the Jews increased in Matthew, whose favorite word for the Jewish leaders was 'hypocrites'. After the fall of the temple, a remnant of the Pharisees who survived moved to Galilee. This was the beginning of Rabbinic Judaism. Matthew’s polemic against the Jews may be understood that these two groups were now in competition over had the correct understanding of Judaism.

Luke: The Compassionate Jesus

Luke’s gospel is notable for the fact that Jesus spends more time with the poor and outcasts than in any other gospel. He included unique parables, such as The Prodigal Son or The Good Samaritan, that highlighted mercy and compassion.

Another major theme of Luke is forgiveness. This is the only gospel where Jesus forgives one of the other crucifixion victims and his tormentors from the cross. Luke’s Jesus is also a new Moses, but Luke extends that theme to frame his story within the entire history of Israel. The ministry of Jesus in Luke also mirrors Elijah and Elisha. In style and structure, Luke added new Bible stories to the history of Israel, updating God’s promises in the lifetime of Jesus.

John: The Man from Heaven

John’s Jesus is less a prophet of Israel than a philosopher discoursing on the state of the universe. John differs significantly from the first three; no parables and no exorcisms. John’s opening preface is famous: "The Word [logos, the philosophical principle of rationality] became flesh and made his dwelling among us" (John 1:14). This concept would lead to the doctrine of the incarnation, the divine putting on flesh. Most of John’s speeches begin with metaphors: such as "I am the good shepherd" (10:11) or "I am the bread of life" (6:35). The "I am" is a reference to when Moses asked God his name. John dismissed the problem of Jewish disbelief by claiming they were not children of Abraham, but "belong to your father, the devil" (8:43). John does not have Jesus returning to earth. The kingdom is the turning of the inner man, in a new understanding of spiritual enlightenment.

Historicity & Canonization

Scholars consistently debate the topic of the historical Jesus, with lists that vary from scholar to scholar. For example, did the disciples abandon Jesus? The fact that all four gospels related it with few attempts to rationalize it convinces many of its historicity. This event comes under the criteria of embarrassment. In other words, this event must have been so well-known that the writers were required to deal with it.

Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John are categorized as canonical gospels. Kanen was a Greek form of measurement used to suggest a norm. It came into use by the Church Fathers as a way in which to distinguish orthodoxy, the 'correct beliefs'. In the 2nd century CE, there were dozens of other gospels, some of which - the Gnostic gospels - had radical views of Jesus. Gospels that did not follow these four were deemed heresy (Greek: haeresis, meaning 'a school of thought'). The process of putting together what would become The New Testament took several decades. When the Roman emperor Constantine I (r. 306-337 CE) converted in 312 CE, he deemed these four as the only true gospels.