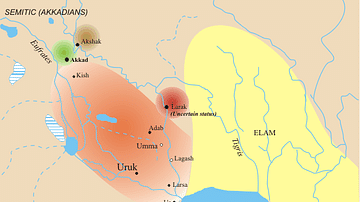

Literature (from the Latin Littera meaning 'letters' and referring to an acquaintance with the written word) is the written work of a specific culture, sub-culture, religion, philosophy or the study of such written work which may appear in poetry or in prose. Literature, in the west, originated in the southern Mesopotamia region of Sumer (c. 3200) in the city of Uruk and flourished in Egypt, later in Greece (the written word having been imported there from the Phoenicians) and from there, to Rome. Writing seems to have originated independently in China from divination practices and also independently in Mesoamerica and elsewhere.

The first author of literature in the world, known by name, was the high-priestess of Ur, Enheduanna (2285-2250 BCE) who wrote hymns in praise of the Sumerian goddess Inanna. Much of the early literature from Mesopotamia concerns the activities of the gods but, in time, humans came to be featured as the main characters in such poems as Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta and Lugalbanda and Mount Hurrum (c.2600-2000 BCE). For the purposes of study, Literature is divided into the categories of fiction or non-fiction today but these are often arbitrary decisions as ancient literature, as understood by those who wrote the tales down, as well as those who heard them spoken or sung pre-literacy, was not understood in the same way as it is in the modern-day.

The Truth in Literature

Homer's soaring odes to the grandeur of the Grecian fleet sailing for Troy or Odysseus's journey across the wine-dark sea were as real to listeners as his descriptions of the sorceress Circe, the cyclops Polyphemus or the Sirens. Those tales which today are regarded as myth were then considered as true and sacred as any of the writings contained in the Judeo-Christian Bible or the Muslim Quran are to believers. Designations such as fiction and non-fiction are fairly recent labels applied to written works. The ancient mind understood that, quite often, truth may be apprehended through a fable about a fox and some unattainable grapes. The modern concern with the truth of a story would not have concerned anyone listening to one of Aesop's tales; what mattered was what the story was trying to convey.

Even so, there was a value placed on accuracy in recording actual events (as ancient criticism of the historian Herodotus' accounts of events shows). Early literary works were usually didactic in approach and had an underlying (or often overt) religious purpose such as in the Sumerian Enuma Elish of 1120 BCE or the Theogony of the Greek writer Hesiod of the 8th century BCE.

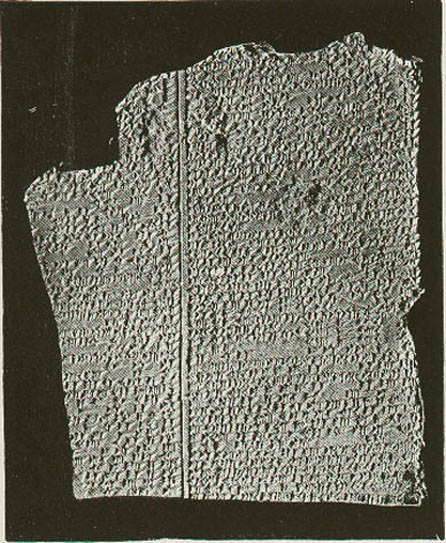

One of the earliest known literary works is the Sumerian/Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh from c. 2150 BCE which deals with themes of heroism, pride, nationality, friendship, disappointment, death, and the quest for eternal life. Whether what happened in the tale of Gilgamesh 'actually happened' was immaterial to the writer and to the listener. What mattered was what the audience was able to take away from the tale.

The best example of this is a genre known as Mesopotamian Naru Literature in which historical figures feature in fictional plots. The best-known works from this genre include The Curse of Agade and The Legend of Cutha, both featuring the great Akkadian king Naram-Sin (r. 2261-2224 BCE), grandson of Sargon of Akkad (r. 2334-2279 BCE, father of Enheduanna). Both of these works have Naram-Sin behaving in ways which are contradicted by physical evidence and other, more factual, writings. The purpose of Naru Literature, however, was not to relate what `really' happened but to emphasize a moral, cultural, and religious point.

Examples of Ancient Literature

The Pyramid Texts of Egypt, also considered literature, tell of the journey of the soul to the afterlife in the Field of Reeds and these works, unlike Mesopotamian Naru Literature, presented the subject as truth. Egyptian religious culture was based on the reality of an afterlife and the role the gods played in one's eternal journey, of which one's life on earth was only one part. Homer's Iliad recounts the famous ten-year war between the Greeks and the Trojans while his Odyssey tells of the great hero Odysseus's journey back home after the war to his beloved wife Penelope of Ithaca and this, like the other works mentioned, reinforced cultural values without a concern for what may or may not have happened concerning the war with Troy.

The story told in the biblical Book of Exodus (1446 BCE) is considered historical truth by many today, but originally could have been meant to be interpreted as liberation from bondage in a spiritual sense as it was written to empower the worshipers of Yahweh, encouraged them to resist the temptations of the indigenous peoples of Canaan, and elevated the audience's perception of themselves as a chosen people of an all-powerful god.

The Song of Songs (c. 950 BCE) from the Hebrew scripture of the Tanakh, immortalizes the passionate love between a man and a woman (interpreted by Christians, much later, as the relationship between Christ and the church, though no such interpretation is supported by the original text) and the sacred aspect of such a relationship. The Indian epic Mahabharata (c.800-400 BCE) relates the birth of a nation while the Ramayana (c. 200 BCE) tells the tale of the great Rama's rescue of his abducted wife Sita from the evil Ravna. The works found in the Assyrian King Asurbanipal's library (647-627 BCE) record the heroic deeds of the gods, goddesses and the struggles and triumphs of heroic kings of ancient Mesopotamia such as Enmerkar, Lugalbanda, and Gilgamesh. Scholar Samuel Noah Kramer points out that the early Sumerian works - and, indeed, Sumerian culture as a whole - resonates in the modern day on many levels and is especially apparent in literature. Kramer writes:

It is still apparent in a Mosaic law and a Solomonic proverb, in the tears of Job and a Jerusalem lament, in the sad tale of the dying man-god, in a Hesiodic cosmogony and a Hindu myth, in an Aesopic fable and a Euclidean theorem, in a zodiacal sign and a heraldic design. (5)

Originality in Ancient Literature

Most early works were written in the poetical metre which the writer had heard repeated over time and, therefore, the dating of such pieces as the Enuma Elish or the Odyssey is difficult in that they were finally recorded in writing many years after their oral composition. The great value which modern-day readers and critics place on 'originality' in literature was unknown to ancient people. The very idea of according a work of the imagination of an individual with any degree of respect would never have occurred to anyone of the ancient world. Stories were re-tellings of the feats of great heroes, of the gods, the goddesses, or of creation, as in Hesiod and Homer.

So great was the respect for what today would be called 'non-fiction', that Geoffrey of Monmouth (1100-1155 CE) claimed his famous History of the Kings of Briton (which he largely made up) was actually a translation from an earlier text he had 'discovered' and Sir Thomas Malory (1405-1471 CE) famed as the author of the Morte D'Arthur, denied any original contributions to the work he compiled from earlier authors, even though today it is clear that he added much to the source material he drew from.

This literary tradition of ascribing an original work to earlier, seemingly-authoritative, sources is famously exemplified in the gospels of the Christian New Testament in that the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, understood by many believers to be eye-witness accounts of the ministry of Jesus, were written much later by unknown authors who chose names associated with the early church.

Literature encompasses forms such as poetry, drama, prose, folklore, epic tale, personal narrative, poetry, history, biography, satire, philosophical dialogues, essays, legends and myths, among others. Plato's Dialogues, while not the first to combine philosophical themes with dramatic form, were the first to make drama work in the cause of philosophical inquiry. Later writers drew on these earlier works for inspiration (as Virgil did in composing his Aeneid, based on Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, between 30-18 BCE) and this tradition of borrowing lasted until the time of Shakespeare (1564-1616 CE) and continues in the present day.