The history of tobacco use in the Americas goes back over 1,000 years when natives of the region chewed or smoked the leaves of the plant now known as Nicotiana rustica (primarily in the north) and Nicotiana tabacum (mostly in the south). After European colonization, tobacco would become the most profitable crop exported from the Americas.

This plant grew wild but came to be cultivated by the natives for use in religious rituals and hunting parties as it was thought to expand the mind and heighten one's sensations overall. After 1492 CE, European colonization of the West Indies and South and Central America shifted the focus of tobacco to recreational use. By the mid-1500s CE, tobacco had become the most profitable export from the Spanish and Portuguese colonies of the Americas, primarily Nicotiana tabacum.

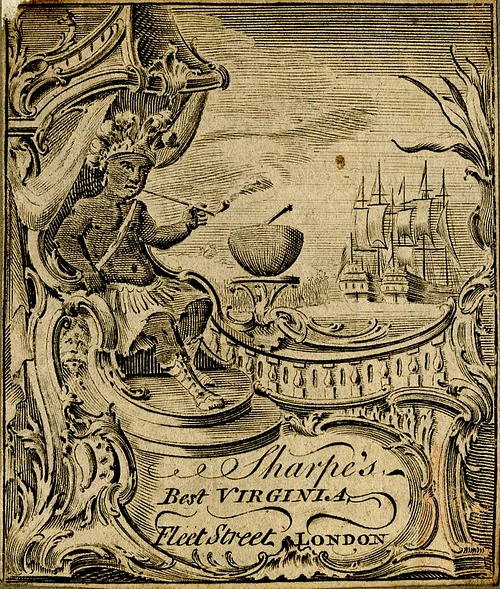

The secret of their Nicotiana tabacum blend was closely guarded by the Spanish – it was against the law to share seeds or plants with non-Spaniards – but travelers or merchants would do so anyway. When England began to colonize North America in the late 16th century CE, Sir Walter Raleigh (l. c. 1552-1618 CE) introduced the older, rougher, strain of tobacco – N. rustica – to Britain. By this time (c. 1585 CE), tobacco had already become a popular, recreational drug in the country, but N. rustica was a much harsher smoke than the Spanish N. tabacum.

The English colony of Jamestown was established in 1607 CE and a hybrid of various strains of N. tabacum was brought and planted by the merchant John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622 CE) in 1610 CE. Rolfe's crop not only made him wealthy but saved the Jamestown Colony of Virginia and further popularized tobacco use in England, throughout Europe, and in the rest of the world. Tobacco plantations expanded throughout Virginia as Jamestown itself began to grow, taking more land from the Native Americans of the region, and this practice finally resulted in the Powhattan Wars (1610-1646 CE) which drove out most of the original inhabitants and made more room for even larger plantations.

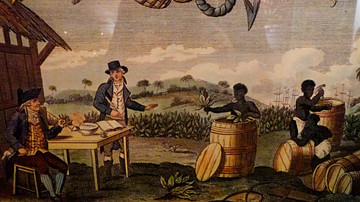

The decrease in the practice of indentured servitude after 1676 CE, and the intense labor required for tobacco crops, led to the increase in importing African slaves and enslaving Native Americans. As tobacco became more popular, and more commercial businesses were established for its cultivation and sale, more land and more slaves were required. The original use of tobacco by the natives was forgotten as the plant became the most lucrative cash crop of the Americas.

It continued to fuel the colonial economy, contributed to the unrest which resulted in the American War of Independence (1775-1783 CE), increased tensions in the country leading up to the American Civil War (1861-1865 CE), and was the cause of the Tobacco Wars of the early 20th century CE. In the modern era, tobacco has been recognized as the leading cause of preventable deaths but continues in use by people around the world as one of the most accepted and popular recreational drugs.

Native American Uses & Colonization

Tobacco, along with the "three sisters" (beans, maize, and squash), potatoes, and tomatoes, was among the most significant crops cultivated by the natives prior to European colonization of the Americas. The plant was considered sacred and was frequently smoked or chewed as an appetite suppressant, a stimulant, for medicinal purposes, and to allow for communion with the spirit world. When Christopher Columbus (l. 1451-1506 CE), arrived in Cuba, the indigenous people offered him tobacco as a gift. Columbus seized on the plant and exported it to Spain where it found a large market.

Columbus instituted the feudal system of the encomienda which offered the natives protection from himself and his men, primarily, in return for labor. Tobacco became one of the main crops harvested on the large colonial plantations and, as demand for the plant grew in Europe, the Spanish overlords worked the natives harder. The Spanish priest Bartolomé de las Casas (l. 1484-1566 CE), who later witnessed the encomienda system first-hand, noted the brutality of the Spanish masters in his A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. After relating a number of atrocities the indigenous people suffered at the hands of the Spanish, he comments:

By the ferocity of one Spanish Tyrant (whom I knew), above two hundred Indians hanged themselves of their own accord [rather than continue to suffer in servitude] and a multitude of people perished by this kind of death. (23)

The Spanish had refined the original plant so that it smoked more easily and had a more pleasant taste, and this, of course, made it even more popular abroad. In 1561 CE, the French diplomat Jean Nicot de Villemain (l. 1530-1604 CE), who had been stationed in Lisbon, Portugal, returned to France with tobacco plants. He introduced tobacco to the French court as a medicine that could cure headaches and calm the nerves. Tobacco became an instant success at court, then in monasteries, and finally among the people in general. Nicot was rewarded by the French crown and his name was given to the active ingredient in tobacco, nicotine. The new market in France required greater efforts in production in the Americas. As tobacco became more profitable, more land was taken for production and more natives for forced labor.

Jamestown & John Rolfe

This same pattern would repeat itself in North America after Jamestown was established by the British in 1607 CE. Between 1607-1610 CE, Jamestown struggled, losing up to 80% of its population and, in 1609 CE, resorting to cannibalism just to survive. In 1610 CE, the merchant John Rolfe arrived along with Sir Thomas Gates (l. c. 1585-1622 CE) and Thomas West, Lord De La Warr (l. 1577-1618 CE) and reversed the colony's fortunes. De La Warr instituted a policy of conquest without compromise against the native Powhatan Confederation while Gates reformed both the colonists and their settlement. It was Rolfe, however, who saved the colony, expanded it, and provided justification for taking more Native American land when the tobacco seeds he had arrived with flourished and he became wealthy from the production and sale of Virginia tobacco.

Tobacco had already been cultivated in the regions around Virginia by the native Adena culture (c. 800 BCE - 1 CE), as evidenced by artifacts such as the Adena Pipe and others, and was continued by the Hopewell tradition (c. 100 BCE-500 CE), successors of the Adena, in modern-day West Virginia, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and Indiana. The native Powhatans had inherited tobacco cultivation, but this was the N. rustica variety. Rolfe's blend was the smoother N. tabacum, but his skill with the plant made it more popular than Spanish tobacco. Scholar Iain Gately comments:

John Rolfe's experiment heralded a rapid and permanent change in the fortunes of England's colonial enterprise. Englishmen understood the value of tobacco and needed little persuasion to finance its cultivation. The London marketplace welcomed increasing shipments of Virginian weed. The tobacco crop of 1618 was 20,000 pounds. Four years later, despite an Indian attack that killed nearly one-third of Virginia's colonists, the settlement sent a crop of 60,000 pounds. By 1627, the shipment totaled 500,000 pounds, and two years later that tripled. (72)

Although De La Warr had pushed a policy of conquest, it had not proved successful, and after he returned to England Rolfe tried a different approach: alliance through marriage. In 1614 CE, he married Pocahontas (l. c. 1596-1617 CE), daughter of the Powhatan chief (referred to by the colonists as Chief Powhatan). It does not seem that Rolfe initially thought of his marriage as a political strategy – the couple were genuinely attracted to each other – but it served the purpose of uniting the natives and colonists for a few years and allowed for greater expansion of tobacco plantations.

Slavery & Tobacco

These farms were worked by indentured servants – people who, voluntarily or involuntarily, agreed to serve a master for seven years in return for passage to the New World and a land grant – but as the farms expanded, more labor was required than these servants could provide. Gately comments:

A solution appeared to Jamestown's labour problem in the form of a Dutch trading ship which dropped anchor in Chesapeake Bay in 1619. The colonists bought twenty African slaves who were set to work in the tobacco fields. The Dutch traders recognized a promising market and returned in subsequent years with more slaves for sale and slavery quickly became essential to the colony's economy. (73)

These early slaves seem to have been treated differently than those who were brought to the colony later. Scholar David A. Price notes:

Although it is tempting to assume that these first recorded Africans in English America were also the first slaves, there is evidence to suggest they were not. They may instead have had the legal position of indentured servants, like many of the white newcomers, eligible for freedom after completing a period of service. (197)

Part of the evidence Price references is the presence of free blacks in the colony prior to 1640 CE who had received land just as white indentured servants had. The year 1640 CE marks a turning point in the treatment of black servants as opposed to white servants in the case of the black indentured servant, John Punch. Punch objected to his treatment by his master and left his service, without fulfilling his contract, in the company of two other servants who were white. When the three were caught, the two white servants had their servitude extended by four years while Punch was sentenced to slavery for the rest of his life. Slavery was institutionalized in Virginia by 1661 CE and, although there were still free blacks in the colony, race now played a much larger part in community affairs and policies than it had previously.

Expansion & Economy

By 1661 CE, the Powhatans had been defeated in three separate wars and the colonists had discovered that Native Americans did not make the best slaves. This realization did nothing to stop them from selling the natives to others, but the white landowners found African slaves to be stronger and able to endure labor longer. The colony expanded further as more indentured servants completed their contracts and were given land and the farms in the interior began encroaching on the lands the Powhatans had retreated to.

In 1676 CE, one of the interior landowners, Nathaniel Bacon (l. 1647-1676 CE) mounted a revolt (Bacon's Rebellion) against the governor William Berkeley (l. 1605-1677 CE), demanding better lands for farmers in the interior and the massacre or relocation of the Powhatans still in the area who would sometimes raid these farms. Berkeley refused Bacon's demands, and the insurrectionists then burned Jamestown. The rebellion fell apart when Bacon died of dysentery, but the authorities recognized the danger of continuing to award land grants to indentured servants who might then use their resources to fund revolt and so ended that policy.

From that point on, manual labor on the plantations would be taken care of by Africans purchased as slaves. Slaves who worked tobacco plantations soon were regarded as more valuable than those who worked in cotton or rice fields because tobacco required more skill to harvest. New slaves were apprenticed to older veterans of the fields to learn these skills and slave families were frequently separated when a skilled tobacco slave was kept but his or her family sold.

Tobacco & the Revolution

As the European demand for tobacco grew, more land was required for plantations and so, first, more Native Americans had to be removed from their tribal lands and, second, more Africans were needed as slaves. The colonies of Maryland and North Carolina became the next two greatest tobacco producers after Virginia, and by the early 1700s CE, all three were exporting thousands of pounds of tobacco to Europe every year. The British monarchy discouraged the production of cotton in the colonies owing to the economic policy of mercantilism (which balances exports over imports) so tobacco became the primary cash crop. Even though James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE) objected to tobacco, he could not argue with the profits and settled for taxing tobacco instead of banning it.

The tobacco farmers stamped their product with seals to identify it, and certain plantations became known for better tobacco than others. Shipments of tobacco would arrive in London where they were handled by merchants, who would push one brand of tobacco for a higher price over others. These merchants also periodically depressed tobacco prices while still providing large loans to the colonial planters. The plantation owners, therefore, found themselves in the position of owing substantial debt they were unable to pay due to depressed London markets.

By this time (c. 1750 CE), tobacco was used in the colonies as currency and so the London merchants could demand payment on the loans in tobacco when planters found they could not pay in cash. This situation contributed to the outrage colonists felt over England's policies in the colonies and encouraged the rebellion that became the American Revolutionary War since a number of the Founding Fathers, including Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, were tobacco farmers.

Civil & Tobacco Wars

Tobacco continued to inform the economy and policies of the United States into the 19th century CE. As the northern states became more industrialized, they required less slave labor, and many abolished the institution. The southern states, however, continued to rely on slaves for labor in the tobacco and cotton fields. Southern goods were frequently shipped to the north and were taxed but, the states felt, nothing of consequence was coming from the north to them as compensation; disagreements over equitable trade and the southern states' defense of slavery finally led to conflict.

Southern states broke with the union that had been formed after the Revolution, declaring themselves a separate entity, the Confederate States of America. Northern states responded by defining this action as rebellion and so the American Civil War (more properly known as the War Between the States) was begun. By the time the south was defeated in 1865 CE, slavery had been abolished, large plantations could no longer function as they once had, and former slaves now had to be paid a fair wage.

The southern states were able to get around the new model by instituting laws on vagrancy whereby someone (almost always a black man) newly arrived in town, who could not provide a legal address, was arrested and sentenced to work on a local plantation. Planters who were provided with these “workers” were able to produce more tobacco at less cost than others with more modest farms who paid their laborers. The farmers sold their product to a distributor who then marketed it to the public, and those with the cheapest labor grew rich enough to also manage distribution.

The biggest distributor in the 19th and early 20th centuries was American Tobacco Company founded by James Buchanan Duke (l. 1856-1925 CE) who had nothing to do with production and everything with sales. He acquired all rights to the new cigarette-rolling machine in 1881 CE which was able to produce 400 cigarettes a minute. Having lowered his costs, he cut his prices, forcing competitors out of business who then sold their companies to him, allowing Duke to form a monopoly on the market. He then offered lower compensation to farmers for their crops which eventually resulted in the Tobacco Wars (better known as the Black Patch Tobacco Wars) of 1904-1909 CE in the region of Black Patch, Tennessee, a collection of counties so-named for the dark smoke from the tobacco-curing process.

The wars were a series of conflicts between tobacco suppliers and distributors and a coalition of farmers calling itself the Planter's Protective Alliance which burned storehouses, farms, and warehouses and periodically hanged sharecroppers who worked on farms supplying Duke. The wars ended when the leaders were arrested in 1908-1909 CE and the American Tobacco Company was dismantled by the federal government in 1911 CE.

Conclusion

Cigarettes had been looked down upon as associated with the lower-class and poor while the pipe or cigar was the preferred method for smoking tobacco by the affluent. Mass production and mass marketing, however, changed that, and by World War I (1914-1918 CE) cigarettes were included in military rations and associated with patriotism. Tobacco use, by this time, had become common practice worldwide, even though some countries had tried to ban it, even going so far as to execute tobacco merchants and users.

In the present day, efforts by groups such as the American Cancer Society have proved somewhat more effective and health warnings or images of diseased lungs are required on tobacco products. Tobacco companies are also no longer allowed to advertise on television or in magazines, and health professionals continually stress smoking tobacco as a cause of lung cancer. Even so, people around the world continue to use tobacco in spite of decades of warnings on its dangers.

Recognizing the plant's popularity, some Native American groups are now trying a different approach to curb smoking: to revive the sacred nature of tobacco. Those involved in these efforts claim that they have seen a reduction in the number of smokers in their community who have come to recognize tobacco in its sacred form, carefully cultivated from the earth to final product, as it was over 400 years ago, and so now treat it, and themselves, with greater respect.