Printed Christmas cards became popular in the Victorian period (1837-1901) thanks to a combination of cheaper printing techniques and even cheaper post, with the arrival of the Penny Black postage stamp. Coming in all shapes, sizes, and materials, Christmas cards were sent in their millions to all corners of the British Empire. Victorian illustrators created an entire mythology of exactly what we imagine a European Christmas should look like with their now-classic scenes of present-covered Christmas trees, holly, robins, sleighs, and snow-covered country lanes. When we dream of a white Christmas, it is the festive cards of the 19th century which are largely responsible for that evergreen imagery.

Origins

Adults have, of course, been writing letters to each other for centuries. Even before there was an official public post system, letters were delivered in person, by servants, and via transport coaches. There had also been prints made from the 15th century, using woodcuts or copperplate printing techniques, especially for calendars. It was, though, in the Victorian period that several factors conspired to make printed Christmas cards the hugely popular phenomenon they became.

The historians Antony and Peter Miall suggest in The Victorian Christmas Book that the origins of cards for the festive season lie in the classroom. From the 18th century, schoolmasters had their pupils work on a 'Christmas Piece' in the month of December. This work involved pupils selecting a sheet of fine paper and producing a sample of their writing, principally to show off to their parents evidence of their academic progress that year. The paper often came with a decorated engraved border, and by the 19th century, it was popular for the pupils to draw their own decorative borders using coloured ink. "These offerings were the forerunners of the great Victorian Christmas Card" (Miall, 37).

Other sources of inspiration for the decorative Christmas card may have been printed music sheets with decorative borders and covers, engravings commissioned to mark important anniversaries, school reward cards for hard-working pupils, fine illustrated notepaper, and the more ornate varieties of visiting cards which were left when one called upon someone and they were not at home.

The First Christmas Card

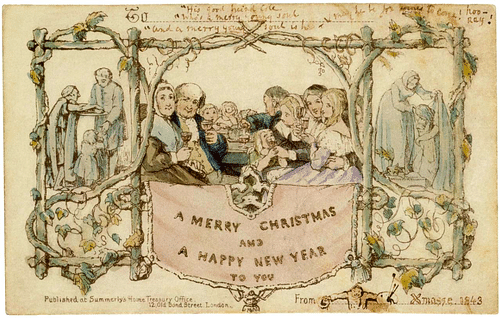

Sir Henry Cole (1808-1882) was a civil servant who had, in 1840, reformed the British postal system by helping to create the Universal Penny Post where senders used the now-famous Penny Black postage stamps. Cole would later become the first director of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. In 1843, Cole had a brilliant idea. Not only could he save himself writing different individualised letters to his friends and family at Christmas but he could also brighten the season with a colourful card printed for the express purpose of sending his compliments of the season. Accordingly, Cole commissioned John Callcott Horsley (1817-1903), an artist and illustrator who was a member of the Royal Academy, to produce the first printed Christmas card.

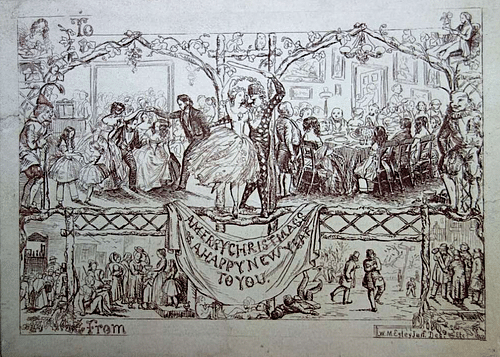

Horsley's design for the card, which was about the size of an ordinary visiting card (2 x 3 inches or 5 x 7.5 cm), showed different generations of the Horsley family raising a toast – presumably to the absent friend who is the recipient of the card – while flanked with scenes showing acts of charity, then, as now, an important element of the Christmas season. On the left are people giving food to the needy, and on the right, they give clothing. There was a border of a wood frame intertwined with ivy, and below the main image a greeting of "A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to You". There was a space along the very top and bottom of the card left blank to write a short handwritten and personalised message to the receiver. One thousand such cards were printed and then hand-coloured. The cards went on sale to the public at the rather high price of one shilling per card. Perhaps unsurprisingly for a new and relatively expensive idea, there were few buyers.

The Idea Catches On

Fortunately for the future of Christmas cards, the royal family was enthusiastic for all things Christmassy. In particular, Prince Albert (1819-1861) brought German Christmas traditions to England such as the Christmas tree. It was, though, the younger members of the royal family who adopted the idea of sending each other handmade greeting cards both at Christmas and New Year. Queen Victoria must have approved since she later started the trend of public figures sending 'official' Christmas cards showing more often than not themselves and their family in a festive setting.

Then in 1844, there was another attempt at the commercial Christmas card, and this was much more successful. Mr W. C. T. Dobson sold a printed card which carried an illustration of the "Spirit of Christmas". In 1848, a card printed by William Maw Edgley (1826-1916) repeated the theme of Cole's card but added scenes of general merriment and holly to the imagery. Printers now knew they were onto a good thing, and they became more and more ambitious with the designs of their cards which were available to buy in stationers and bookshops. From 1879, rather than pricey single cards, people could buy cheap packs of cards from tobacconists and toy shops, often imported from Germany. This development went hand-in-hand with the new half-penny post for postcards, and so now people of all classes could send Christmas cards to their loved ones.

Victorian Christmas Card Designs

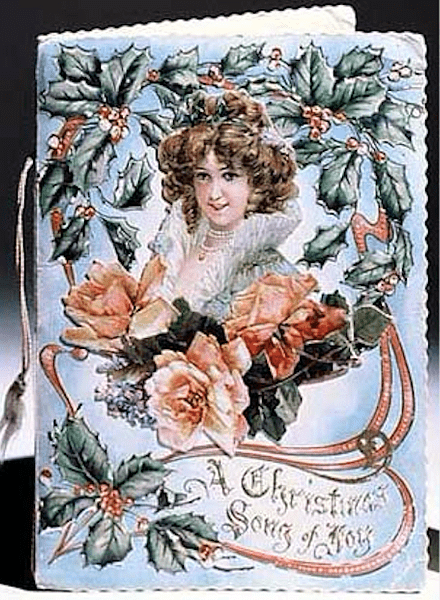

The first cards were printed on small single sheets of card, but they soon progressed to come in all shapes and sizes. Victorian Christmas cards were typically lithographed and hand-coloured before colour-printing took over. Many used embossed paper, sometimes with cut-out parts to resemble lace, particularly for borders. There were even cards decorated with ribbons, tassels, real lace, tinsel, and coloured glass. Satin, silk, and brocade were also popular materials to enhance the feel of the card. The most exotic of cards were scented, had padded additions, and incorporated pressed flowers. One card for sale boasted it was made of no fewer than 750 separate pieces. If one creation reflected the Victorian love of accumulating individual beautiful materials to create an even more beautiful finished article, it was the Christmas card. With so many possible materials being used in a single card, it is no wonder that draper's shops included them in their Christmas stock.

There was a great variety in the shape of cards, too, with the most popular ranging from the classic rectangular form to oval, circular, diamond, crescent, and bell-shaped cards. Some cards were folded, others made into fan shapes, or they reflected the object they illustrated such as a post box or purse. Cards might include moving parts or flaps that could be opened to reveal an additional scene or message. Some had tabs that, when pulled, moved the legs and arms of a character on the front of the card or they had a disk that could be turned to show different scenes in a central window.

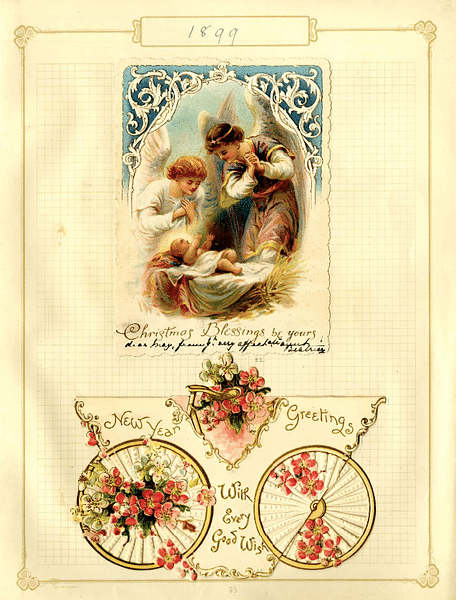

There were all kinds of subjects depicted on cards, many of which included humorous cartoons and everyday life, sometimes not at all related to Christmas. Religious themes remained popular such as angels and scenes from the Nativity, but there was a definite shift away from these to more secular subjects as the Victorian era progressed. Victorian illustrators were not without humour or fear of the risqué, nor did they miss the opportunity to trick the viewer with many cards showing two scenes depending on which direction the card was held.

Victorian illustrators were largely responsible for what we today imagine as a classic 'Christmas scene': old churches and country lanes in the snow, sleigh rides, plump robins, glistening holly and mistletoe, and presents on or under the Christmas tree. The popular snow scenes on Victorian Christmas cards reflected the string of harsh winters in England through the 1830s and 1840s. White Christmases became much rarer thereafter, but the scene in people's imaginations was by then set. In the same way, the Christmas food we imagine being eaten by Dickensian characters in the 19th century is, like in the cards, always golden roast turkeys and great steaming Christmas puddings the size of cannon balls.

Father Christmas was a popular figure on cards, but he evolved over the decades, his appearance morphing from a Falstaffian character to a jolly old man with blue trousers and a crown of holly, and finally on to his definitive red suit with white fur trim. Father Christmas' mode of transport also evolved to keep up with the times, The Victorian Father Christmas used any means he could to reach people's chimneys such as the popular bicycle of the 1880s, the new motor car of the 1890s, the ever-growing modern railway network, or even a hot air balloon.

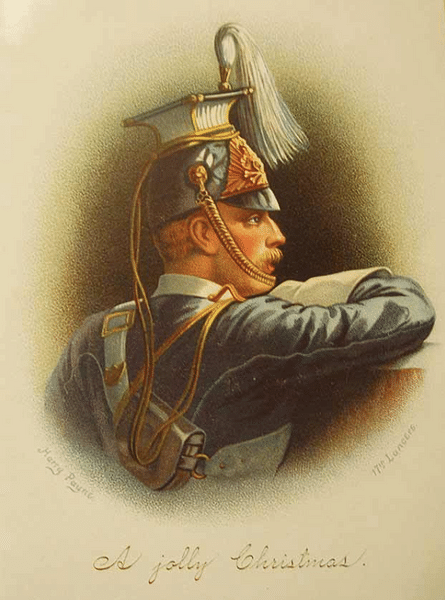

Christmas cards had become such a staple part of the season that they now attracted the top artists to illustrate them, names like Linnie Watts, who produced a series of cards showing children, and Harry Payne, who drew soldiers, a poignant theme for those with loved ones serving far from home in the armed forces of the British Empire.

Cards changed over time as tastes changed. For example, black backgrounds to make the main picture more striking were popular in the 1870s. Cards reflected modern trends in art, too. By the end of the century, art nouveau designs were appearing, with highly decorative designs and subjects inspired by the works of such fashionable artists as Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939). With cards being sent around the world, the tradition quickly took root in other countries, notably in the United States from 1874, with the cards printed by Louis Prang (1824-1909), popularly known as "the father of American Christmas cards".

Christmas Card Texts

On the front, inside or on the reverse of the card, the printed text also became more varied through the years, and below are some 19th-century examples:

Love and Peace with thee abide

Through the holy Christmastide!

Very happy may it be

Christmas time to thine and thee.

We live in deeds

in thoughts not breaths

not years

in feelings not in figures

on a dial.

May Christmas bring thee peace and plenty,

Barns and cellars never empty.

A horn of honest wholesome beer,

Will warm the heart, the spirits cheer.

May your Christmas happy be,

Fraught with every joy for thee;

And throughout each year in store,

Peace be with thee evermore.

Cards often came with longer printed texts such as poems or several verses of popular carols. An example of a typical verse within a Victorian Christmas card is:

Oh, Life is but a river;

And in our childhood, we

But a fair running streamlet

Adorn'd with flowers see.But as we grow more earnest,

The river grows more deep;

And where we laugh'd in childhood,

We, older, pause to weep.Each Christmas as it passes,

Some change to us doth bring;

Yet to our friends the closer,

As Time creeps on, we cling.(Miall, 43)

Collecting Christmas Cards

Beautifully made and capturing memories of the season, the Victorian middle classes became avid collectors of Christmas cards, which explains why it became common to have the year printed somewhere on the card. Perhaps the most famous card collector was George Buday – he even wrote a celebrated book on the history of Christmas cards, his The Story of the Christmas Card – and he donated his collection of over 3,000 cards to the Victoria and Albert Museum. This museum today has over 15,000 Christmas cards in its archives and each Christmas it reprints old Victorian designs so that they can, once more, just as in days of yore, carry people's Christmas wishes far and wide.