The Christmas holiday has gathered around it customs and traditions for over two millennia, some of which even pre-date the Christian festival itself. From gift-giving to the sumptuous spread of a Christmas dinner table, this article traces the history of the celebrations from Roman times to the Victorian era when our modern take on the holiday was firmly established in both deed and literature. Although many of the traditions described herein are universal to all Christian countries, particularly up to the end of the Middle Ages, we here present the Christmas traditions largely in terms of the Anglo-Saxon experience.

Origins: Saturnalia

Several of the traditions today strongly associated with Christmas have a very long history indeed, even pre-dating the Christmas celebration itself. Early Christianity sought to distance itself from pagan practices and so later Roman emperors closed down ancient sacred sites, prohibited rituals, and ended sporting games that had once honoured pagan gods. However, changing the habits of ordinary people was a different matter. The pagan festival of Saturnalia had been particularly popular, and its traditions that had endured for a millennium were, in many cases, simply transferred to the new festival of Christmas.

Saturnalia was a week-long Roman festival held between the 17th and 23rd of December that honoured the agricultural god Saturn, nicely encompassing the winter solstice, another event of significance in the pagan calendar. The fact that this was the merriest of all Roman holidays probably derived from Saturn's role as a ruler when the world was basking in a golden age of happiness and prosperity. The festival, which dates back to the 5th century BCE, was described by the 1st-century BCE Roman poet Catullus as "the best of times".

Saturnalia involved giving to friends and family gifts like candles, coins, and food. Less formal clothes were worn, games played, feasts enjoyed, and there were even role-reversal parties. Social restrictions were eased a little, and activities like gambling or appearing drunk in public were less frowned upon. It all sounds rather familiar, does it not? The festival was pushed later in December over time, and just as Athens' Parthenon had to bear a church and bell tower within its columns, so, too, Saturnalia, one way or another, morphed into the Christmas celebration.

A Medieval Christmas

During the medieval period (500 to 1500), the celebration went from strength to strength. It was the longest holiday of the year, typically the full 12 days of Christmas. From the night of Christmas Eve (24 December) to the Twelfth Day, Epiphany (6 January), people took a much-needed rest, largely thanks to the lull in agricultural activity mid-winter.

Christmas preparations began in the home of the poor as well as the rich. Winter foliage was available, and greenery was gathered to decorate the house with garlands. Holly, ivy, and mistletoe had long been admired by the Celts and were associated with protection against evil spirits and fertility. A giant double hoop of mistletoe usually took pride of place in one's living room. The fertility connection explains, then, why a tradition developed of couples kissing under the mistletoe, picking off a bright white berry with each peck given. Another important feature of a home at Christmas, and another link with pagan practices, was the Yule log. This prodigious piece of tree trunk was placed in the hearth and kept lit for all 12 days of the holiday.

The point of Christmas was, of course, to celebrate the birth of Jesus Christ. Attendance at church was expected of all; indeed, in certain periods it was compulsory. Local churches made a real effort to provide a service worthy of the occasion. Candles were lit, and glittering gilded altarpieces were opened, many for this special day only. The choir sang and added extra songs and dynamic dialogues known as 'troping'. From this activity sprang the tradition of using individual speakers or actors to perform scenes from the story of the Nativity. Over time, the Christmas nativity became a piece of theatre with costumes and even live animals.

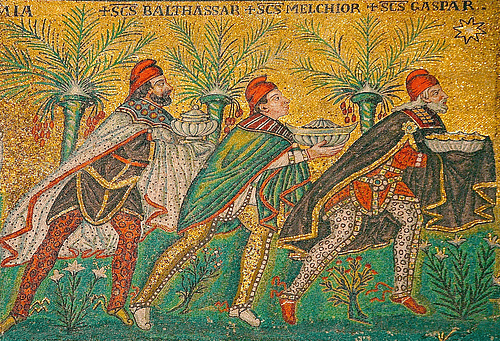

In reference to the Magi's three gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh when they visited the baby Jesus in Bethlehem, gifts were given to friends and family. For the rich, fine clothes and jewellery were the norm; for the less well-off, nicer food than usual, a bundle of firewood or simple wooden toys like spinning tops and dolls were eagerly anticipated. Serfs, alas, were often expected to present their lord with extra bread and eggs, and perhaps a chicken at Christmas. In the other direction, the landed gentry did give gifts to some of their free staff who might receive a bonus of clothing or winter supplies. Gifts were given again on the 1st of January. Known as 'first-gifts', these were thought to indicate one's fortunes in the coming year. Another omen for the future was who one's first guest of the year was. People visited each other's homes on New Year's Day, and for this activity, known as 'first-footing', it was considered most desirable if the guest was male, dark-haired, and flat-footed.

In the Middle Ages, as now, food was a big part of the pleasure of Christmas. The rich had to outdo their already handsome manor tables, providing guests with meats like roast peacock, swan, or boar's head, as well as treats like salmon and oysters. Desserts were similar to today's festive fare: nuts, oranges, cakes, fruit custards, figs, and dates. To drink, there was sweetened or spiced wine, cider, and ale. The great Christmas meal was generally an early lunch. The table cloth was changed after every course and entertainments included music, acrobats, jesters, and plays put on by roving minstrels. That parties everywhere could get out of hand is attested by records of watchmen being paid to ensure property was not damaged over the 12-day holiday, particularly the big parties held on the eve of the 6th of January, known as Twelfth Night.

The poor enjoyed more modest entertainment like cards and dice, carols, playing musical instruments, board games, telling folktales, and enjoying traditional party games like permitting one person to be the 'king of the feast' if they found a bean in the special bread or cake – everyone else then had to mimic the 'king' (a role-reversal game that echoed Saturnalia's similar 'Lord of Misrule'). Free public entertainments of the holiday were put on by churches and guilds such as puppet shows, pantomimes, and pageants. There were, too, the masked mummers, professional entertainers who visited homes and performed for a small fee or a bit of refreshment. Another enduring medieval tradition that continues in our Christmases today is helping those less fortunate than ourselves. Leftovers from the grand lunch in a manor were often given to the poor, and some lucky individuals might even be invited to the meal itself, for example, two of the lord's serfs.

An Elizabethan Christmas

As the Middle Ages came to a close, the dominant role of the medieval Church in people's lives began to ease a little. Attendance at certain church services remained compulsory by law, but the Reformation and its dislike of imagery and show in churches did diminish somewhat the splendour of Christmas services. During the Elizabethan Era (1558-1603 CE) 'holy days' continued to be the main source of public 'holidays' – a term now being used for the first time – but there were also more secular activities establishing themselves as popular traditions. For example, Advent had been a time of fasting before Christmas, beginning on Saint Andrew's Day, 30 November. By now, though, it was becoming more of a countdown to the Christmas holiday which was still 12 days long. Many more children were now attending schools than in the Middle Ages, and they were given the two weeks off.

Gift-giving continued, as did the idea that this was a time of year when acts of charity should be pursued. The tradition of giving gifts on the 1st January remained strong, and this included Elizabeth I of England herself, who regularly received jewels, extravagant dresses, and feather fans from her courtiers. Poorer folk often gave pins, gloves, and fruit on this day.

The food was perhaps the part most looked forward to; indeed, the Christmas feast was now so extravagant that the baker of the house required much more preparation time. For this reason, the holidays came to begin on the 'Eve' of Christmas, 24 December, usually the late afternoon of that day. By now, the 25th had taken over as the big day of the holidays in terms of private celebrations and parties, eclipsing those previously held on Twelfth Night.

In homes decorated with evergreens and candles, feasts included lots of meat and seafood since these were still rare guests on the table at other times of the year. Pies, spiced fruitcakes, nuts, and 'brawn' (pickled pork) were especially popular, as was wassail, a type of spiced ale that was usually drunk from a brown bowl to the accompaniment of songs. The popularity of games (especially cards) and entertainment continued as before. Social rules were relaxed, too, as by now most people expected. Reversing the roles of the sexes, allowing apprentices to get the better of their masters, and having two commoners act as the 'king and queen of the feast' brought much hilarity and occasions for people to demonstrate their wit. The two monarchs were typically chosen because they had found a bean and a pea respectively inside a spiced cake.

Christmas was an opportunity for travel and seeing the kingdom's sights. With no public roads, travelling by horse and carriage was slow and uncomfortable; nevertheless, the more intrepid could visit sights like Francis Drake's Golden Hind ship in London, which had made the first English circumnavigation of the globe (1577 to 1580). The sparkle of the Crown Jewels in the Tower of London was another popular attraction in the Tudor period.

The very name Christmas did come under fire during the English Reformation when the reference to the Catholic Mass was seen as undesirable within the Anglican Church. Christmas itself was seriously threatened by the Puritans, those Christian extremists who preferred to fast on Christmas day. Fortunately for everyone, the decision to cancel the celebration of Christmas by law was reversed in 1660. The holiday was back and now firmly established as the most important of the year, in this respect, replacing the celebration of Easter for many people.

A Victorian Christmas

The next leap forward in how Christmas was celebrated came during the reign of Queen Victoria from 1837 to 1901, a period which witnessed some significant new traditions that have since become a lasting part of the holiday season. The Victorians displayed a great nostalgia for the merry Christmas festivities of the medieval period. Just as many today wistfully romanticise the Christmases of the Victorian period, so in the 19th century, writers like Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832) eulogised on the Christmases of yore. In effect, the holiday had become an exercise in capturing that elusive myth of a past golden age, an exercise which, in many ways, continues today. The Victorians certainly ensured that such medieval elements as a Christmas morning church service, feasting, games, gifts, and pantomimes continued to enjoy their status as essential activities of the season.

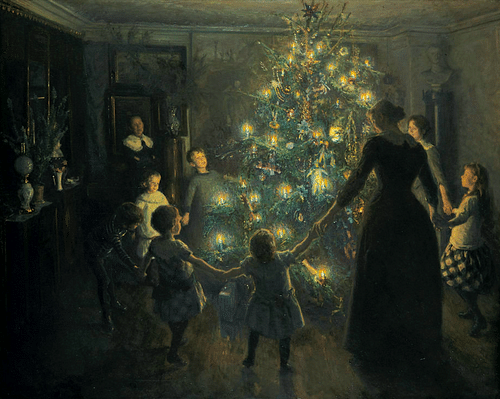

Queen Victoria's husband was Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the Prince Consort (l. 1819-61), and he introduced to Britain the tradition of the Christmas tree, which was popular in his home country. Not the first royal to have a Christmas tree in England, nevertheless, from 1841, Prince Albert began a lasting tradition which soon spread from town squares to living rooms across the country, the idea being spread by popular illustrated magazines that revealed the private festivities of the royal family. Mistletoe remained an important element of decoration, but the tree eventually replaced it as the centrepiece of the home at Christmas. The young fir tree was decorated with candles and small presents (toys, sweets, charms, and candied fruit) hung from its boughs that were destined to be distributed to the Christmas guests who might have their name tagged to their gift.

Carols and songs were sung around the family piano or by small groups of carol singers outside people's homes on Christmas Eve, their reward being a glass of punch or a hot pie. The first book of carols actually dates back to 1521, but it was the Victorians who spread this tradition far and wide, collecting long-forgotten carols and adding their own to newly published anthologies.

A more efficient postage system and the introduction of the Penny Black stamp in 1840 meant that correspondence increased and a tradition developed of sending friends and distant family a Christmas card, first introduced in England in 1843. Coming in all shapes and sizes, these were lithographed, hand-coloured, and often boasted ribbons and lace. There were all kinds of subjects depicted on cards, but one recurring theme was snow scenes, a reflection of the string of harsh winters in England through the 1830s and 1840s. White Christmases became much rarer thereafter but the scene in people's imaginations was by then set.

A huge range of gifts was available from shops that festooned their windows to entice indecisive shoppers, and many sent out catalogues for those not able to visit in person. Rather than being made in the home, mass-produced toys were now available, often imported from centres in Germany and Holland. Not just simple affairs made of wood, toys became ingenious. Miniaturised mechanisms made dolls walk and trains trundle. Presents were now given primarily on Christmas Day or Christmas Eve. The 26th of December became known as Boxing Day in Britain because this was the day when employers traditionally gave a box of gifts and leftovers to their servants and workers.

The greatest gift-giver at Christmas is, of course, Father Christmas. The jolly figure with the long white beard who visits homes on Christmas Eve to leave good children presents has his origins in the 4th-century Saint Nicholas, Bishop of Myra in Anatolia who delighted in distributing gifts, including sacks of gold. As one recipient had received her gold via the chimney and it landed in a sock, so the familiar method of delivery became established. The Saint is celebrated on 6 December and still, in many countries today, that is the time when children hang up their stockings or slippers. Father Christmas was not only inspired by Saint Nicholas but he also incorporated elements of the 'Spirit of Christmas' of folklore, which explains his more jovial and spirit-loving side, a trait children hopefully appeal to by leaving him out an alcoholic drink of some sort on Christmas Eve. The gift-giving jovial figure has many guises, from Christkind (Germany) to Santa Claus (United States). It was the American version of the red-suited man with a proud paunch – seen from around 1850 – that won the day, it seems, in the popular imagination of just who brings the best presents.

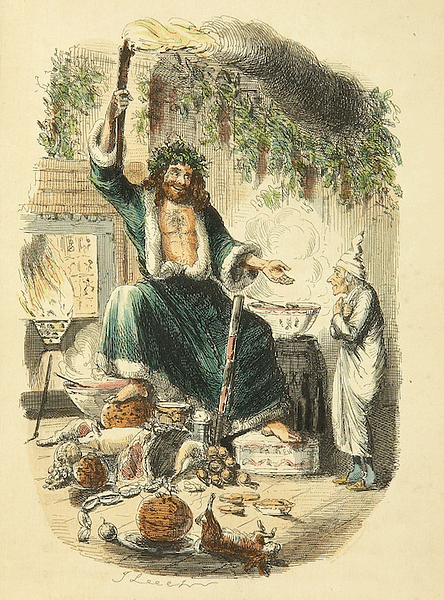

There was a general rise in living standards, although of course not for everybody, and this meant that a special meat was now required for the Christmas feast. Roast beef had been popular in the north of England and goose in the south, but as the century wore on, up stepped the turkey to take centre stage on many a dinner table. Even less well-off families could have a large bird for Christmas if they joined such schemes as The Goose Club, paying into an account weekly to have the bird at Christmas which was then cooked at a baker's. Either side of the roast fowl, there was soup, oysters, lamb, port jelly, fruit, nuts, and whatever other delicacies a family could afford for this the greatest meal of the year.

The finale was a steamed Christmas pudding, often called a plum pudding after its main ingredient (already replaced by currants and raisins in the Victorian era). A silver coin such as a Threepenny piece was placed inside the pudding, an echo of the medieval bean in the cake tradition. The spherical pudding was decorated with a sprig of holly and covered in rum or brandy so that it could be served alight. It became such an anticipated part of Christmas that even sailors, lighthouse keepers, and polar explorers carried one to eat on the big day. Mince pies were popular, then with a mix of meat and fruit (the former has been discarded in the modern version). The spiced fruit cake of the Elizabethans became the traditional iced Christmas cake, eaten after dinner or for supper, perhaps with a little cheese and a glass of port.

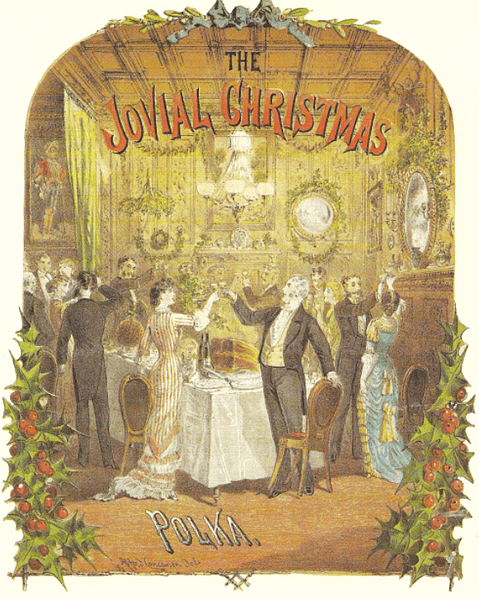

The table was decorated with Christmas crackers, paper rolls that two people pulled open with a crack, and inside were small toys, charms, silhouette portraits, sweets, paper hats, and mottoes. There was, too, a change in timing, some families continued to eat a Christmas lunch, perhaps a little later than a normal one, while others ate a Christmas dinner in the evening. After the meal, there was dancing, singing, recitations, perhaps a little turn of conjuring from a guest or some magic lantern slides. There were games, too, like charades, Blindman's Buff, Hunt the Slipper, or Snap Dragon (picking out raisins from a bowl aflame with brandy).

All of these Victorian Christmas activities were captured, celebrated, and preserved for future generations by writers of the period, and none did so more successfully than Charles Dickens (1812-1870). Dickens' festive tale A Christmas Carol, with its story of the reformed miser Ebenezer Scrooge, has itself become a staple part of Christmas ever since its publication in 1843.

The traditions have, of course, kept growing, with additions like Rudolph the red-nosed reindeer, children meeting Santa in the local department store, and chocolate advent calendars. Nowadays, electric lights may have replaced the candles on the tree, churches are not quite as busy as they used to be, the Yule log is now usually chocolate, and many of the cards have become electronic, but the traditions that have run through the centuries to celebrate Christmas Day continue each and every year to enchant and inspire as they have always done.

Midnight strikes. You hear it in the silence of Christmas night as you hear it at no other time. The great day has come to an end. If you are abroad you will be startled by your own solitude. You will understand how truly is Christmas the festival of the home.

Christmas London, G. R. Sims

(Miall, 149)

This article is dedicated to the author's late mother Ruth Cartwright who, cheerfully busy at her stove, ensured each and every Christmas was merry and bright with festive fare.